How can you retain students after they have enrolled?

How can you retain students after they have enrolled? Some tentative research based guidelines for practice

Nick Zepke, Linda Leach, Tom Prebble

Massey University

Student retention, persistence and completion have become major issues for tertiary educators and increasingly institutions are researching their own retention challenges and solutions. This paper brings together findings from two New Zealand based research projects that have investigated the retention issue. The first is a major research synthesis drawing on 146 international studies. From this literature the research synthesized 13 propositions to assist institutions understand and act on their retention challenges. The second is a New Zealand study funded by the Teaching and

Learning Research Initiative (TLRI), which, in part, asked students returning for a second enrolment in 7 tertiary institutions, what caused them to think of withdrawing, to actually withdraw, or what enabled them to stay. The paper will summarize the 13 propositions, précis some of the findings from the TLRI study and attempt to bring these together as tentative guidelines for practice.

1

How can you retain students after they have enrolled? Some tentative research based guidelines for practice

Nick Zepke, Linda Leach, Tom Prebble

Massey University

Introduction

The cost of early student departure to the United Kingdom taxpayer is 100 million pounds annually according to one estimate (Yorke, 1999). Given this financial impact of attrition and the uncounted human costs associated with early student withdrawal, it is no wonder that governments throughout the western world demand improved student outcomes such as better retention, persistence and completion. The reasons for early student withdrawal have been well researched in the United States over many years and more recently in Australia and the United Kingdom. In New Zealand too, there is an increasing interest in researching the departure puzzle (Braxton, 2000) and a number of institutional studies have been completed.

This paper brings together findings from two New Zealand investigations of the retention issue. The first is a major research synthesis drawing on 146 international studies. From this literature we synthesized 13 propositions to assist institutions understand and act on their retention challenges. The second is a study funded by the

Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI), which, in part, asked students returning for a second enrolment in 7 tertiary institutions, what caused them to think of withdrawing, to actually withdraw, or what enabled them to stay. The paper will summarize the 13 propositions, précis some of the findings from the TLRI study and attempt to bring these together as tentative guidelines for practice.

Literature foundations

The student outcomes literature is large. Major syntheses have been published over several decades, primarily in the USA, (Tinto, 1975, 1988, 1993; Pascarella and

Terenzini, 1991, 2004; Astin, 1993, 1997) but also in Australia (McInnis et al., 2000).

Tinto has developed an integrative theory and series of models of student departure.

These have achieved a dominance called almost hegemonic by Braxton (2000).

Vincent Tinto’s 1993 model of student departure has six progressive phases. Two focus on students’ social and academic integration into their institution. Much student retention research is based on these phases. Studies used in our survey tested various

Tinto constructs (Cabrera et al., 1992; Braxton et al., 1995; Padilla et al., 1997;

Braxton & Lien, 2000). Although many aspects have been validated by research, results have been uneven. Braxton and Lien (2000), for example, tested his academic integration construct and found quite different levels of support for it in multiinstitutional and single institution studies.

Tinto’s theory and models are not without critics. They fall into two broad groups - those who wish to revise and improve Tinto’s theories (Cabrera et al., 1992; Braxton,

2000) and those who propose entirely new theoretical directions (Berger, 2001-2002;

Kuh and Love, 2000; Rendon et al., 2000; Tierney, 2000). In our view, those revising

Tinto’s model retain his integrative intent. This results in an assimilation process,

2

fitting the student to the institution. However, those developing new theoretical directions modify integration to include adaptation , where institutions change to accommodate diverse students. In this emerging discourse student departure is influenced by their perceptions of how well their cultural attributes are valued, accommodated and how differences between their cultures of origin and immersion are bridged (Cabrera et al., 1999; Walker, 2000; Berger, 2001-2002; Thomas, 2002).

We have included this emerging discourse in the TLRI study, but are aware that there is, as yet, less empirical evidence supporting it than supports the assimilative model.

Until recently, New Zealand literature on retention was not only sparse but offered few new theoretical insights. Student departure and success is generally conceived within Tinto’s integrative models. Indeed the literature sections and designs of most studies acknowledge Tinto’s work (Leys, 1999; Grote, 2000; Wilson, 2002; Kozel,

2002; Dewart, 2003). Trembath (2004) reports results that parallel those in our research synthesis. Two New Zealand projects have taken a slightly different theoretical approach. Purnell (2002) also acknowledges Tinto’s contribution, but explains her research in terms of Nicholson’s transition cycle. Bennett and Flett’s

(2001) research into the role of Maori cultural identity in student success is related to the adaptation discourse. Fraser (2004) reports an approach taken by her institution, and increasingly in others, to retention issues. This focuses on ensuring that students have the necessary academic skills upon entry.

The Ministry of Education Research Synthesis

We became interested in retention in 2002 when, as members of a team of Massey

University researchers funded by the Ministry of Education, we conducted a synthesis of research on the influences of learning environments on student outcomes in undergraduate tertiary study. We synthesized 146 research studies and reported our work in a variety of publications (Zepke & Leach, 2003; Zepke, Leach & Prebble,

2003; Prebble, Hargreaves, Leach, Naidoo, Suddaby, & Zepke, 2004; Zepke & Leach,

2005). Our synthesis takes the form of thirteen propositions or action statements on how to improve student outcomes. Each proposition evolved from our reading research reports and assessing the strength of evidence provided. We now state the propositions and summarise literature support.

1 Institutional behaviours, environment and processes are welcoming and efficient

Fourteen studies address this proposition. Overwhelmingly they support the idea that student outcomes are enhanced where students are assimilated into the institutional culture. They highlight, for example, the clarity and accessibility of information about the institution and programmes, the impact of enrolment processes, effectiveness of advice about course changes, the flexibility of timetabling and ease of early contact between institution and students.

2 The institution provides opportunities for students to establish social networks

Seventeen studies address this proposition. Evidence suggests that outcomes improve where institutions make personal contact outside classrooms and show commitment to students’ total well-being. Examples include facilitating social networks and promoting social integration through special social programmes such as clubs, cultural groups and sporting activities. Another perspective, while supporting the

3

institution’s role in social integration, is more cautionary and warns that too much social activity can negatively affect academic outcomes.

3 Academic counselling and pre-enrolment advice are readily available to ensure that students enrol into appropriate programmes and papers

Fourteen studies addressed this proposition. They highlight the positive effects of academic counselling and pre-enrolment advice. Students make wrong choices about courses or even the university. The studies synthesised show that readily available pre-enrolment advice and academic counselling is likely to assist retention and improve student outcomes.

4 Teachers are approachable and available for academic discussions

We synthesised 20 studies for this proposition. A recurring theme is that outcomes improve where students have regular and meaningful contact with teachers, both inside and outside the classroom. We found three themes to support the proposition.

The first highlights the importance of teachers nurturing students. The second suggests that teachers have a mentoring role away from their teaching. The third examines the role of teachers in learning communities.

5 Students experience good quality teaching and manageable workloads

Twenty three studies addressed this proposition, although they generally addressed quality of teaching as one factor. Quality teaching respects students, is fair and unbiased, culturally sensitive, caring and motivational. Contact with the teacher needs to be regular, sustained and positive. Teaching methods need to suit students’ levels of independence. Student workload is regarded as a key factor in influencing students’ outcomes.

6 Orientation/induction programmes are provided to facilitate both social and academic integration

Fourteen studies informed our synthesis. Results show that orientation programmes help overcome problems with course selection and induction and improve academic outcomes. Evidence is very strong that orientation programmes provide anticipatory socialization, whereby individuals come to anticipate correctly the values, norms and behaviours they will encounter at university.

7 Students working in academic learning communities have good outcomes

We used 18 studies in this synthesis. Academic learning communities range from combining courses, creating cohort groups within larger classes, to institutions deliberately creating a homogeneous ethos in relation to ethnicity, gender, domicile or religion. In one major American study a sense of community was one of only four significant persistence factors identified by students. Two large United Kingdom studies also found that the absence of opportunities to learn collaboratively influenced decisions to leave.

8 A comprehensive range of institutional services and facilities is available

Twenty studies reported on the impact of institutional services and facilities. Services included child care, pastoral/religious care, English language support, financial aid, counselling, health service, library support, international students’ assistance, women’s resource centre, student housing and employment services, study skills assistance, student clubs, sports facilities and cafeteria. The research results create a

4

strong argument that providing institutional services facilitates positive student outcomes. However, a note of caution is sounded in studies acknowledging an often low use of such services.

9 Supplemental Instruction (SI) is provided

SI offers a specific introduction to subjects. It is not remedial, as it identifies highrisk subjects , not high risk students; integrates the development of study skills within an academic subject; is voluntary and open to all students; has SI leaders who are trained in teaching and learning theory and who facilitate group study and problem solving. We found 9 studies of SI. All report that the SI programmes have positive effects on student outcomes.

10 Peer tutoring and mentoring services are provided

We synthesized seven studies for this proposition. Peer contributions to both academic and social integration are important in achieving positive student outcomes.

Indeed some report that the strongest single source of influence on cognitive and affective development is the student’s peer group. Peer group tutoring and mentoring emerge as useful tools in the integration process, for example, in orientation programmes, Supplemental Instruction and learning communities.

11 There is an absence of discrimination on campus, so students feel valued, fairly treated and safe

We found 17 studies indirectly linking discrimination to students’ outcomes. It often emerged as one factor in retention. Discrimination may be disguised, for example, as

‘social isolation’, ‘alienation’ and ‘difficulty making friends’, even ‘feeling homesick’. Studies show that the climate created within an institution impacts on student outcomes. As student diversity increases institutions must create climates that welcome, accept, respect, affirm and value diversity, creating ‘an accepting culture’ or ‘ethos’.

12 Institutional processes cater for diversity of learning preferences

We synthesised 15 studies for this proposition. These suggested that students expect institutions to fit their lives. Changes in patterns of attendance, with more students employed outside the institution, consequent changes in their social life and new technologies, reduce integration. Studies suggest that institutions need to change the way they manage the undergraduate experience. They advocate tighter, more coherent yet relevant curricula, small subject-focused learning communities and support structures operating in and out of the institution, enabling students to stay connected with their outside worlds.

13 The institutional culture, social and academic, welcomes diverse cultural capital and adapts to diverse students’ needs

We synthesised 19 studies supporting the need for institutional culture change.

Institutional culture is experienced at several levels – social, academic and organisational. The studies found that tertiary students arrive at an institution with particular cultural capital. Where this is not valued or accepted they are more likely to experience acculturative stress. Studies found that where institutional cultures are accepting of difference and facilitate a greater match with students’ personal identity, higher rates of student retention and success are achieved.

5

The Teaching Learning Research Initiative (TLRI)

The research synthesis whetted our appetite to do more retention research. This time we wanted to focus on New Zealand. We applied for a grant from the Teaching and

Learning Research Initiative (TLRI). While our TLRI proposal drew on the 13 propositions, these were too diverse and complex to test using but a single datagathering tool. We decided to use a 360-degree research design involving a number of data gathering tools seeking the views of students, teachers and administrators - all official participants in the learning process. The results reported in this paper used a questionnaire as research tool but this represents just one slice of the 360-degree pie.

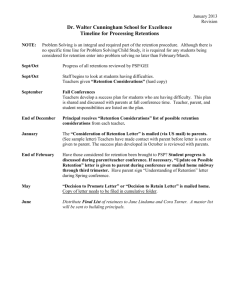

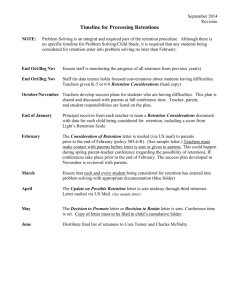

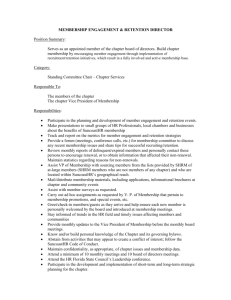

Because previous studies (Braxton & Lien, 2000) found that research results obtained from multi-institutional samples differed from those achieved from single institutions case studies, we decided to take a single institution, a case study approach. We sought a good geographic spread, a variety of programme levels, different sized institutions, at least one offering some distance delivery, at least one with a rural hinterland, at least one with a significant Maori and Pasifika presence. In the end we selected seven institutions that together matched our inclusion criteria. Admittedly, final selection also depended on a willing partner being available. Figure 1 shows how our selection criteria were distributed across the institutions.

Institution/

Profile

Degree Programme

Sub-degree Programme

Large Institution

Medium Institution

Small Institution

Mixed Delivery

Face-to-Face Delivery

Rural Hinterland

Maori Presence

Pasifika Presence

A

B

C

D

Figure 1: Profiles of the seven participating institutions

E

F

G

The survey instrument was distributed by researcher/practitioners within their institutions to groups of students returning to study after one enrolment period and according to a specific profile. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they had ever thought about withdrawing from all or some of their study in 2003 and whether they actually did withdraw. Depending on their answer they were asked to complete one of two different sub-scales, one containing 22 Likert-type items, the other 11.

Students who had thought about withdrawing from all or part of their studies, and actually did withdraw from at least parts of their studies, filled in the first sub-scale.

Students who never thought of withdrawing filled in the second.

681 students completed the questionnaire in six of the seven institutions. Of these, 40 were from Institution A, 84 from Institution B, 135 from Institution C, 57 from

Institution D, 103 from Institution E, 106 from Institution F and 156 from Institution

G. The response rates were highly variable: 24% from Institution A; 27% from

Institution C; 100% from Institution D; 42% from Institution E; 77% from Institution

F and 22% from Institution G. Even though the number of surveys received from some institution was small, we decided that a return rate in the 20-30 percent range

6

was acceptable and we did not send out a second survey to Institutions A, C, D, E, F and G.

TLRI survey support for the 13 propositions

We now report findings that illuminate the 13 propositions. We found that seven of our propositions are supported in the student data, but also that a major reason for students departing early cannot be attributed to institutional factors alone. We will now discuss these findings before using them and the 13 propositions to construct some guidelines for action.

There is support for the original 13 propositions

We did not structure the student questionnaire to directly capture information about all of the propositions that inform this enquiry. However, case study data from the student survey support seven of the 13 propositions. o Proposition 3, the importance of academic counselling , is supported. We assumed that where suitable academic counselling was available, students would feel they were taking the right course. Nearly half of students who actually withdrew, considered ‘wrong course’ as an important or major reason. Of those who never considered withdrawal, 83 % said an important or major reason for this was that they had selected the right course. o There is some evidence supporting Proposition 4 - that the accessibility of teachers and quality teaching are important . Of the students who actually withdrew, almost one fifth gave teaching quality as a major reason and more than one-quarter felt the course did not suit the way they learned. Half of the students never considering withdrawal supported the proposition that teacher support was important in continuing commitment to their studies. o Proposition 5, a manageable workload , was very well supported in the survey. A third of students considering withdrawal gave heavy workload as an important or major reason, while a fifth left because workload was an important or major factor. Three fifth of students never considering withdrawal gave ability to manage workload as an important or major reason. o Proposition 8 holds that institutional support should be available . Data show that students considering withdrawal used support services to varying degrees. In

Institutions A, E and G 20% of students rate the use of services as an important or major factor; while in Institution C not one student did. Of those who never considered withdrawal, almost one-fifth felt that the availability of support services was an important or major factor. Given these data it is possible to argue that availability of student support services is a factor in student retention and success. o Proposition 12 - the need for institutions to cater appropriately for diverse learning preferences was also supported. More than a quarter of those who actually withdrew indicated that the course did not address the way they learned.

Students considering withdrawal at one Institution G ranked this first; those at

7

Institution E third equal. Of those who neve considered withdrawal 28% felt that flexibility in the way they were treated was an important or major reason. o We also found support for Propositions 11 and 13: students feel valued, fairly treated and safe and adapts to diverse students’ needs.

The data suggest that institutions can still do much more to meet the needs of diverse students. Of those who considered full withdrawal from their studies, around one-fifth gave inadequate teaching, a lack of recognition of their learning needs and an absence of a sense of belonging as important or major reasons for thinking of withdrawal.

When responses to all 11 statements on the questionnaire’s subscales were ranked in order of importance these reasons all featured in the top half of those factors giving rise to thoughts of withdrawal. Of those who did withdraw, two factors,

‘did not suit the way I learn’ and ‘felt I did not belong’ also ranked in the top half.

The impression that institutions did not really value diversity was enhanced by the data from students who had never considered withdrawal. These students placed all items that described institutional norms and practices as supportive of their diversity in the bottom half of the items they thought were important or major in helping them to stay.

Non-institutional factors affect retention

Offsetting these institutional factors leading to early withdrawal were some surprising results. When we designed the questionnaire we wanted to focus on factors that were within institutions’ ability to influence. But we knew from the retention literature that non-institutional factors were also important (Yorke, 1999). So we included some questions designed to inform us about the importance of such factors. A very important factor in students’ decisions to withdraw is a non-institutional one – there was too much going on in my life . Nearly one-half of students saw this as an important or major reason for withdrawing. Conversely 57% of those never considering withdrawal felt they were able to manage life issues. Bloody-minded determination was another non-institutional factor important in retention. Students overwhelmingly rated ‘I was really determined to succeed’ as the most important factor in their continuing to study. In three institutions it was rated important by over 80% of the students who considered withdrawal. While it could be argued that claiming personal responsibility for persistence and success might be an expected response, the data are such that we cannot overlook the importance of this finding. A key question for institutions is how to foster personal qualities such as determination as a means of improving retention and completion.

Guidelines for practice

At this early stage of the TLRI project we can do no more than sketch out some suggestions for institutions arising from the propositions and our survey. It is important to note that at this stage much data still awaits analysis and these guidelines may yet undergo change.

1.

Ensure availability of sound academic advice . Prospective students need to understand the nature of courses, the workload involved and teaching methods used before they enrol. If necessary, students should be counselled out of taking a particular course. The drive for ‘bums on seats’ will not lead to good retention.

8

2.

Foster a climate where good teaching is valued

. ‘Good teaching’ means more than effectively transmitting information in classrooms. It includes support for students outside the classroom and, most importantly, the ability to appropriately match teaching methods to different situations.

3.

Create an institutional culture that is learner-centred.

Teaching is a servant to learning so should meet the learning needs of diverse students. This requires flexibility in teaching, assessment and also administrative systems.

4.

Nurture institutional support structures and services.

Even though support services are often underused, for students at risk of leaving early, they are often vital. The function of various support services need to be understood by all staff within the institution who must consider themselves as reference point to appropriate services.

5.

Operate an early warning system.

If, as the student survey research suggests, factors outside the institution’s control are frequently responsible for students leaving early, then an early warning of imminent departure will minimize actual departure. Systematic reporting of absences, missed assignments, sudden deterioration of grades to designated people within the institution are examples of early warning processes.

6.

Be wary of generalized guidelines; research your own institution . Both research studies reported in this paper support Braxton and Lien’s (2000) and

McInnis et al.’s (2000) finding that individual institutions could face quite unique retention challenges; challenges that are obscured by generalizations.

For example, 71% of the respondents from Institution F considered ‘wrong course’ an important or very important reason for withdrawal. In contrast, no one in Institutions A and D thought this was important or major. So, more academic advice would be unlikely to improve retention in these institutions.

Conclusion

In this paper we have brought together findings from two New Zealand investigations of the retention issue. The first is a major research synthesis drawing on 146 international studies. From this literature we synthesized 13 propositions to assist institutions understand and act on their retention challenges. The second is a study funded by the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI), which, in part, asked students returning for a second enrolment in 7 tertiary institutions, what caused them to think of withdrawing, to actually withdraw, or never consider withdrawal.

The paper summarized the 13 propositions and some of the findings from the TLRI study and brought these together in 6 tentative guidelines for practice.

Acknowledgements : We gratefully acknowledge the Ministry of Education who funded the research synthesis and the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative

(TLRI) who funded the survey reported here. We also acknowledge the contributions to our partners in the seven tertiary institutions participating in the TLRI research.

References

Astin, A. (1993). What matters in college? Four critical years revisited. San Francisco: Jossey

Bass.

Astin, A. (1997). The changing American college student: Thirty year trends, 1966-1996. The

Review of Higher Education , 21(2), 115-135.

9

Bennett, S. & Flett, R. (2001). Te Hua o te Ao Maori . He Pukenga Korero: A Journal of Maori

Studies, 6(2), 29-34.

Berger, J. (2001-2002). Understanding the organizational nature of student persistence: Empiricallybased recommendations for practice. Journal of College Student Retention , 3(1), 3-21.

Braxton, J. (Ed). (2000). Reworking the student departure puzzle . Nashville: Vanderbilt University

Press.

Braxton, J. & Lien, L. (2000). The viability of academic integration as a central construct in Tinto’s interactionalist theory of college student departure. In J. Braxton. (Ed). Reworking the student departure puzzle . Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 11-28.

Braxton, J., Vesper, N., Hossler, D. (1995). Expectations for college and student persistence.

Research in Higher Education , 36(5), 595-612.

Cabrera, A., Castaneda, M., Nora, A. & Hengstler, D. (1992). The convergence between two theories of college persistence. Journal of Higher Education, 2, 143-164.

Cabrera. A., Nora, A., Terenzini, P., Pascarella, E. & Hagedorn, L. (1999). Campus racial climate and the adjustment of students to college: A comparison between white students and African-

American students. Journal of Higher Education , 70(2), 134-160.

Dewart, B. (2003). Towards a model for student retention . Unpublished paper.

Fraser, C. (2004). Setting and assessing entry criteria: to do or not to do? Building bridges: diversity in practice . Proceedings of the ATLAANZ Conference, New Plymouth.

Grote, B. (2000). Student retention and support in open and distance learning . Lower Hutt: The

Open Polytechnic of New Zealand.

Kozel, K. (2002). Establishing a learning community: Focus on students through mentoring .

Unpublished paper.

Kuh, G. & Love, P. (2000). A cultural perspective on student departure. In J. Braxton. (Ed).

Reworking the student departure puzzle . Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 196-212.

Leys, J. (1999). Student retention: Everybody’s business . Paper presented at the AAIR Conference.

McInnis, C. (2001). Signs of disengagement? The changing undergraduate experience in Australian universities. Inaugural Professorial Lecture, August 2001. Retrieved on 18 November 2004 from http://www.cshe.unimelb.edu.au/downloads/InaugLec23-8-01.pdf

McInnis, C., Hartley, R., Polesel, J. & Teese, R. (2000). Non-completion in vocational education and training and higher education . Canberra: DEETYA.

New Zealand Ministry of Education. (2002).

Tertiary Education Strategy 2002/07. Wellington.

Padilla, R., Trevino, J., Gonzalez, K. & Trevino, J. (1997). Developing local models of minority student success in college. Journal of College Student Development , 38(2), 125-135.

Pascarella, E. & Terenzini, P. (1991) . How college affects students: Findings and insights from twenty years of research . San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Prebble, T., Hargreaves, H., Leach, L., Naidoo, K., Suddaby, G. & Zepke, N. (2004). Best evidence synthesis: Teacher/educator and learning environment influences on student outcomes in undergraduate tertiary study. Phase 1 report. Unpublished paper .

Purnell, S. (2002). A map, a bicycle and good weather: The transition to undergraduate study .

Thesis: Massey University.

Rendon, L., Jalomo, R. & Nora, A. (2000). Theoretical considerations in the study of minority student retention in higher education. In J. Braxton. (Ed). Reworking the student departure puzzle .

Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 127-156.

Tertiary Education Advisory Commission. (2000). Shaping a Shared Vision . Wellington: New Zealand

Government.

Tertiary Education Advisory Commission, (2001a). Shaping the System. Second Report of the

Tertiary Education Advisory Commission.

Wellington: New Zealand Government.

Tertiary Education Advisory Commission, (2001b). Shaping the Strategy. Third Report of the Tertiary

Education Advisory Commission.

Wellington: New Zealand Government

Tertiary Education Advisory Commission, (2001c). Shaping the Funding. Fourth Report of the

Tertiary Education Advisory Commission.

Wellington: New Zealand Government

Thomas, L. (2002). Student retention in higher education: The role of institutional habitus. Journal of Educational Policy , 17(4), 423-442.

Tierney, W. (2000). Power, identity and the dilemma of college student departure. In J. Braxton.

(Ed). Reworking the student departure puzzle . Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 213-234.

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research , 45(1), 89-125.

Tinto, V. (1988). Stages of student departure: Reflections on the longitudinal character of student leaving. Journal of Higher Education , 59(4), 438-455.

10

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. (2 nd Ed).

Chicago: The University of Chicago Press .

Trembath, V. (2004). ‘Finally it was all too much’: Reasons for leaving early from initial teacher education.

Master of Education Thesis, Auckland College of Education.

Walker, R. (2000). Indigenous performance in Western Australia universities: Reframing retention and success.

Canberra: DEETYA.

Wilson, S. (2002). Retention and success: A practical approach . Paper presented at the Adult

Learning Conference, Wellington

Yorke, M. (1999). Leaving early: Undergraduate non-completion in higher education . London:

Falmer Press

Zepke, N., Leach, L. & Prebble, T. (2003). Student support and its impact on learning outcomes.

Paper presented at the HERDSA Conference, Christchurch, 6-9 July 2003.

Zepke, N. & Leach, L. (2003). Changing institutional cultures to improve student outcomes: Emerging themes from the literature . Refereed paper presented at the NZARE Conference, Auckland,

December 2003

Zepke, N. & Leach, L. (2005). Integration and adaptation: Approaches to the student retention and achievement puzzle. Active Learning in Higher Education, 6(1), 46-59.

11