Chapter 1 - Harvard University

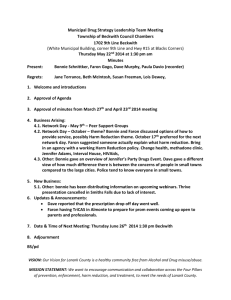

advertisement

I slowly changed my position. I became convinced that stopping a scientific development did not even necessarily prevent the feared misuse…. I also knew that stopping a scientific line of research might prevent potential intellectual and practical benefits. So I decided to concentrate on the ideological stances that fueled the misuses of scientific developments, rather than on opposing new developments in genetics because of their potential negative consequences. I would work on reaching the public and my scientific colleagues with “exposés” of socially loaded claims masquerading as science. I hoped that the awareness of scientists themselves and of an informed public would create sufficient force to ensure more beneficial uses of science. Jon Beckwith, in Making Genes, Making Waves For Immediate Release Contact: Mary Kate Maco Publicity Director 617/495-4713 mary_kate_maco@harvard.edu Still Making Waves Few prominent scientists have been as outspoken, both about their science and the world around them, as Jon Beckwith, now the American Cancer Society Professor of Microbiology and Genetics at Harvard Medial School. His years as an undergrad and then a grad student at Harvard, and years of postdoctoral work both here and abroad, transformed him into both a full-fledged geneticist and a political activist, and culminated in an event that unified his scientific, humanistic, and political leanings: In 1969, he and his colleagues were the first to isolate a gene from the chromosome of a living organism. Announcing this startling achievement at a press conference, Beckwith took the opportunity—equally startling for the time—to issue a public warning about the dangers of genetic engineering. And he hasn’t looked back since. In Making Genes, Making Waves: A Social Activist in Science (Harvard University Press; October 2002; $27.95), Beckwith describes his extraordinary life in science—a career than spans most of the post-war history of genetics and molecular biology and afforded the opportunity to work with the likes of Arthur Pardee, Sydney Brenner, Jacques Monod and Francois Jacob—one that is characterized by a singular commitment to raising the awareness of his fellow scientists and the public to the ethical and social issues surrounding genetic research. From his notorious 1969 press conference to his donation, in 1970, of the prize money from the Eli Lilly Award to the Black Panthers (during his acceptance speech he condemned the practices of the drug industry—of which of course the Eli Lilly Company was a representative); from his role as an early member of the Science for the People and the “Sociobiology Study Group” and in controversies over such issues as “the criminal chromosome” to his current involvement with the Hastings Center in a study of the ethical consequences of genomics, Beckwith has always tried to balance his scientific research with a strong sense of social responsibility. Making Genes, Making Waves is not, however, simply a personal memoir. It delves deeply into some of the major controversies in genetics over the last 30 years, presenting the science in easily understood terms. Ranging from the travails of Robert Openheimer and the atomic bomb and C. P. Snow’s “Two Cultures” to the Human Genome Project and the recent “Science Wars,” Beckwith provides a sweeping view of science and its social context in the latter half of the 20th century. In the end, Beckwith challenges scientists to become more engaged in considering the consequences of their work and to shed their arrogance towards those in the humanistic and social sciences. While his book is full of enthusiasm and delight for science and its approaches to problems, Beckwith’s message to the public is to be aware that science is a human activity influenced by the social biases that affect all of us. At a time when issues of genetics and society are at the fore, these challenges are particularly important. About the Author: Jon Beckwith is American Cancer Society Research Professor of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, Harvard Medical School. Harvard University Press Pages: ; ISBN: 0-6740928-2 Publication date: October 15, 2002 Price: $27.95 Please be sure to visit our web site at www.hup.harvard.edu to find more information about this and other Harvard University Press titles. Chapter 1 The Quail Farmer and the Scientist Chapter 2 Becoming a Scientist Chapter 3 Becoming an Activist Chapter 4 On which side are the angels? Chapter 5 The Tarantella of the Living Chapter 6 Science and politics: does science take a back seat? Chapter 7 Their own atomic history Chapter 8 The Myth of the Criminal Chromosome Chapter 9 It's the devil in your DNA Chapter 10 "I'm not very scary anymore" Chapter 11 Story-telling in science Chapter 12 Geneticists and the Two Cultures Chapter 13 The scientist and the quail farmer Making Genes, Making Waves: A Social Activist in Science Jon Beckwith, Published by Harvard University Press A chance meeting on a train in France leads to a reunion with a long-lost colleague (now a quail farmer in Normandy) and stimulates eminent geneticist Jon Beckwith to reflect on his career as a scientist and political activist within science. Beckwith recounts his often halting steps to becoming a scientist as he is torn between his excitement about genetics and his love of the world of ideas beyond science. His years at Harvard as both undergraduate and graduate student, his postdoctoral work, including three years in Europe, transform him into a political activist as well as a full-fledged geneticist. These experiences culminate in an event that unites his scientific, humanistic and political leanings. In 1969, he and his colleagues are the first to isolate a gene from the chromosome of a living organism. Announcing this startling achievement at a press conference, Beckwith takes the opportunity to issue a public warning about the dangers of genetic engineering. This event initiates for him a long career of political activism within science. Beckwith describes the growth of the radical science movement in the 1970’s and his activism around issues of genetics and society. He points out the potential dangers of the new genetic technologies, but sees the ultimate sources of many of these dangers in the social preconceptions that influence scientists studying the role of genes in human behavior. This stance involves him in controversies over such issues as “the criminal chromosome,” sociobiology, and ethical issues surrounding the Human Genome Project. Because of his activities, he is, at times, demonized and his position as Professor at Harvard Medical School is even threatened. He does not hesitate to reveal the hazards to the scientist who challenges scientific studies from within. But, at the end, Beckwith describes his satisfaction at being able to combine a successful scientific career with a role as writer, commentator and activist. This book is not just a personal memoir. It delves deeply into some of the major controversies in genetics over the last 30 years, presenting the science in easily understood terms. It describes the dramatic changes in biology that took place between the late 1950’s and the present time and the personalities involved. It deals with the differing styles of scientists and how science is presented both within the scientific community and to the public at large. Ranging from the travails of Robert Oppenheimer and the atomic bomb and C.P. Snow’s “Two Cultures” to The Human Genome Project and the recent “Science Wars,” Beckwith’s memoir provides a sweeping view of science and its social context in the latter half of the 20th century. In addition, he describes the social and political environment of 1950's Harvard, early 1960's Berkeley, California, the expatriate scene in Paris of the mid-1960's, the culture shock of his 1970 stay in Naples, Italy and the influence of the social turmoil of the 1970's on his own lab. Beckwith challenges scientists to become more engaged in considering the consequences of their work and to shed their arrogance towards those in the humanistic and social sciences. While his book is full of enthusiasm and delight for science and its approaches to problems, its message to the public is to be aware that science is a human activity influenced by the social biases that affect all of us. At a time when issues of genetics and society are at the fore, these challenges appear particularly important. 5 Blurbs on back cover of book: “MAKING GENES, MAKING WAVES has special credibility coming from one of America's most distinguished microbiologists. It is a must read for any young scientist who is concerned by the tension between the beautiful rationality of science and the sometimes disconcerting outcomes of its application” DAVID BALTIMORE, President, California Institute of Technology, and winner of the 1975 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine “THE RENOWNED SCIENTIST Jon Beckwith wrote Making Genes, Making Waves so that students could learn an oft-hidden truth: it is possible to become a successful scientist and still be a social activist within science.” ANNE FAUSTO-STERLING, Professor of Biology and Women’s studies, Brown University “JON BECKWITH PRESENTS A CANDID and compelling story of his career-long attempt to integrate two roles, that of the research scientist and that of the social activist. With luck, his lucid narrative will inspire others to follow his example.” PHILIP KITCHER, Professor of Philosophy, Columbia University “BECKWITH’S MAKING GENES, MAKING WAVES shows that the commitment to social responsibility is entirely compatible with commitment to science; that love of science can coexist with serious qualms about its social consequences.” DOROTHY NELKIN, Professor of Law and Sociology, New York University. “IT IS RARE TO FIND AN HONEST man describing how he became a first-rate scientist while his mixed feelings about the role and function of science turned him into an effective social activist. Making Genes, Making Waves is an excellent account, by a participant, of the debates about science and society that occurred in the last 30 or 40 years. It is especially interesting that the same man who was engaged in social activism was producing the best of the science that generated so much passion.” FRANÇOIS JACOB, Winner of the 1965 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine