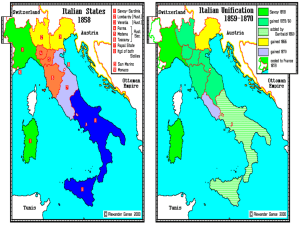

It. Unif. (essay)

advertisement