Trouble in the Boardroom

advertisement

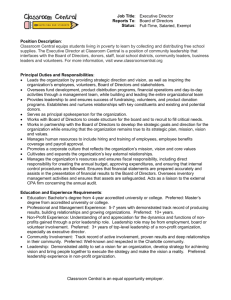

Trouble in the Boardroom Being a director used to be so much fun. Not anymore. FORTUNE Monday, May 13, 2002 By Katrina Brooker Help Wanted DIRECTOR Rub shoulders with Corp. elite. Big $, great perks, travel, stock options, Ideal hours (only 4X/yr.) No experience necessary.* *New laws may let you be personally sued. Your reputation also at risk. If the press smells scandal. you may be chum. On the morning of April 26, 1999, Jane Shaw, chair of the audit committee of McKesson, was expecting to have a great day. She was at the Boulders Resort in Carefree, Ariz., where McKesson board members had gathered to celebrate their $14 billion acquisition of HBO & Co. The deal was expected to be a big success. And now Shaw and her fellow directors were planning to enjoy a few days in the sun while discussing the future of the newly merged companies. Before anyone could hit the pool, though, Shaw called an audit committee meeting to go over a few routine accounting items. There, one of the company's auditors asked a question about how HBOC had accounted for a portion of its revenues in a previous quarter. The amount in question was small--a few million dollars. "But the knitting unraveled from there," Shaw recalls. As it turned out, virtually all of HBOC's numbers were wrong: The company had improperly overstated its revenues by $327 million. "We were devastated," Shaw says. From that moment on, everything about her life as a corporate director changed. Shaw--who is also CEO of Aerogen, a $2.5-million-a-year Silicon Valley medical-technology firm--spent the next three years embroiled in a massive accounting scandal. There were government investigations, shareholder lawsuits, and endless pummelings by the press. Ultimately McKesson had to write off $192 million of HBOC's earnings. For Shaw, the experience has been harder to write off. "It's been very painful," she offers candidly. Scandal. Lawsuits. Tarnished reputations. Oh, how the life of corporate directors has changed! It used to be that a boardroom seat was the plushest of gigs. You got paid lavishly to hobnob with the rich and mighty, swap gossip over a pleasant poached-salmon lunch, and jet home. As one boardroom denizen quoted by FORTUNE summed up, "If you have five directorships, it is total heaven, like having a permanent hot bath.... No effort of any kind is called for. You go to a meeting once a month in a car supplied by the company, you look grave and sage, [and] on two occasions say, 'I agree.' " (That FORTUNE story is from 1962.) Yes, as we said, life has changed. Today's corporate boards, even the most dedicated and efficient, are in upheaval. Thanks to a litany of high-profile blowups--McKesson, Waste Management, Sunbeam, and most recently Enron, Imclone, Global Crossing, and on and on--the entire system of corporate governance is taking cannon fire. Critics charge that boards are mere lackeys to their CEOs, they get paid too much, they work too little. Too often they have little expertise in corporate governance or need remedial financial literacy. And certainly much of the criticism is true. (Didn't O.J. Simpson sit on the audit committee of Infinity Broadcasting? Um...yes, he did.) Just about everyone is investigating ways to ensure that corporate boards fulfill the oversight role that shareholders expect of them. The New York Stock Exchange has set up a committee to study corporate-governance issues for its listed companies. The Securities and Exchange Commission has asked Congress to give it more authority over directors. In June the Council of Institutional Investors is meeting with judges from Delaware (where more than 300,000 companies are incorporated) to air their grievances about corporate governance. Even the Treasury Secretary, Paul O'Neill, has entered the fray. Earlier this year O'Neill proposed (before backpedaling somewhat) that directors face personal liability when they are negligent in uncovering a company's misconduct. (Currently directors are liable only if they intentionally defraud the company or profit at the company's expense.) "It would serve them right to have to pay out of their own pockets," sniffs one Senator's aide. "I bet they'd work a lot harder then." Perhaps. But as Washington and Wall Street debate how to fix the corporate-governance mess, we wondered what the crisis looked like from the perspective of those on the firing line. What's it like to sit on a board these days--when shareholders, regulators, and yes, journalists, are setting their laser sights on you? What happens when things suddenly go wrong? And why would anyone want to sit on a board in this kind of environment? Personal risk has emerged as a factor like never before, says Olivia Kirtley, a past chair of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants who sits on three boards. "When you read in the paper everything that can go wrong, you have to wonder, Is the risk higher than the reward?" One part of the equation that hasn't changed over the decades is the reward side. It's all there--the prestige, the networking, and of course the nice retainer. According to executive-search firm Spencer Stuart, some 5,500 people serve on the boards of companies in the S&P 500. They get paid on average $37,000 a year and make an additional $1,200 per meeting. Big companies like Citigroup and Coca-Cola pay $125,000 a year. In return, directors are expected to spend 100 to 150 hours on company business. That's not a bad deal. But that hourly rate can drop precipitously when something goes wrong. Consider what happened to Rod Hills. When the ex-SEC chairman and board troubleshooter agreed to take over the audit committee of Waste Management in 1997, he had no idea what he was getting into. "I arrived on a Friday, spent the weekend reading the books, and by Monday I saw disaster," he recalls. From that moment on, untangling what became a multibillion-dollar accounting scandal turned into a 24-hour-a-day occupation. "I used to come home on Sundays to change my underwear," he says. Still, it isn't so much the potential time commitment that worries directors these days. It's the subpoenas. Yes, directors are almost always covered--for both their liability and their legal fees--under their corporation's directors-andofficers (D&O) insurance policies. But that doesn't mean they don't have to defend themselves from civil lawsuits, which have increased sharply in the past several years. There were 125% more shareholder lawsuits in 2001 than in the previous year. (The tally is up 331% from 1996.) That means endless depositions, hearings, investigations--and the risk of taking a big financial hit. "The plaintiffs bar sues at the drop of a hat," grouses Phil Laskawy, retired CEO of Ernst & Young, who's now a director at Goodyear and other companies. All the directors FORTUNE spoke with said they'd drop their board seats if they were no longer insulated from liability by their D&O insurance. But in fact that protection may already be slipping (even apart from Paul O'Neill's comments). The insurance industry has been writing tougher policies in recent years that increasingly give them an out. "You can't count on D&O insurance anymore," says Charles Elson, who heads the Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware. Stephen Weiss, an attorney with Holland & Knight who represents corporate boards, agrees. "There are all sorts of exclusions, conditions, and definitions--it all depends on how they write the policies," he says. Three insurers for Enron, for example, have tried to rescind their liability coverage, citing their contention that the insurance was obtained through misrepresentation. (In April a bankruptcy judge ruled that Enron's directors and officers would be covered.) Insurers are getting tough not only about how they write those policies but also about for whom they write them. "We're asking more invasive questions than we have in the past. We look harder at the people--to see how engaged they really are," says Tony Galban, manager of Chubb's board practice. "Boards who just show up and collect a check--I'm not as likely to like them." At the same time, D&O insurance premiums are climbing. They're up 30% on average since the beginning of the year--and by as much as 500% in higher-risk industries like technology. Scariest of all isn't the financial or legal trouble. What has many directors up at night grabbing for the Maalox is fear for their good names, says Marty Lipton, partner of Wachtell Lipton, a New York City law firm that represents directors. Corporate directors tend to be people who have big careers--CEOs, politicians, university presidents. Sitting on the board of a company that's mixed up in an accounting scandal or government investigation can be devastating. "We still don't know all the facts about Enron, but the reputations of those directors have been damaged forever," says Kirtley. And Enron's board was considered an A-list group. So the thinking is, If it could happen to them, why not me? Dick Grasso, the well-regarded chairman of the New York Stock Exchange, knows that fear well. "If you look at CA, when I went on that board eight years ago it was just a rocket to the moon," says Grasso, speaking of his directorship at Computer Associates. Then, in 1998, the company was hit with a slew of shareholder lawsuits over apparent excessive compensation for CA's executives. Then came a barrage of federal probes, a nasty proxy battle, and a tanking stock price. The good times were over. "When it went like this [he points to the ceiling], we could do nothing wrong. When it goes like this [he points to the floor], the world hates you." And the kind of trouble that torpedoes reputations almost always takes directors by surprise. When Shaw of McKesson's board worked on the HBOC acquisition, she thought she'd done her homework: She'd met with external and internal auditors and accountants dozens of times, scoured the company's financial reports, interrogated its management. But she never considered that anyone had been lying to her--and that was ultimately her mistake. All that, not surprisingly, has directors everywhere wondering, Is it worth it? "Sometimes you say, 'Why did I ever do this?' " offers the University of Delaware's Elson, who sat on the board that fired Sunbeam's Al Dunlap. Ken Taylor, a corporate-board recruiter at Egon Zehnder International, has started getting calls from directors saying they want out. "They ask me, 'How can I exit without creating a stink?' " he says. According to recruiter Christian & Timbers, 60% of prospective nominees are now turning down board appointments. Michael Cook, retired CEO of Deloitte & Touche, recently rejected a board seat because he worried that the company's past financial record was spotty. "I thought, There's too much risk here," he says. Surprisingly, many of the directors FORTUNE interviewed acknowledge that all the pressure and scrutiny has an upside too: They are getting better at their jobs. "The best of the best are stepping back and asking, 'Are we as good as people think we are?' " says Grasso. "You want to be pluperfect in this kind of environment--you want to make sure you're not failing the test." Some feel more empowered now to stand up to management. "Directors are whispering in my ear that they are happy about this," says Nell Minow, a shareholder activist who runs the Corporate Library, a Website that provides information on boards. "It gives them a platform to call up their CEOs and say, 'Explain to me why we're not the next Enron.' " Directors now routinely query, Do we have the right accountants? Are we asking the right questions? Are we getting accurate information? "Pressure's good for them," Minow says. "When they're under pressure, they'll do the right thing." Indeed, for some directors getting a company through a rough time can end up feeling like a mark of accomplishment. "You get tired at times," says Shaw, but "you get through it." McKesson, which has recently started to pull out of its crisis, reported a huge rise in earnings last quarter, and its stock is up 144% from its low of $16 in 2000. "To be a part of it has been very gratifying," Shaw says. Which is not to say that the perks of being a director still have the same sweet taste. When asked whether she'd return to the Boulders to celebrate the company's turnaround, she shudders, "I never want to go back there--too many bad memories."