The Normans: Monty`s Proud Ancestors

advertisement

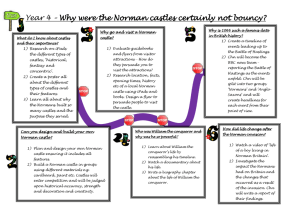

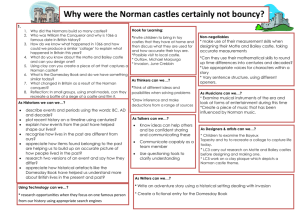

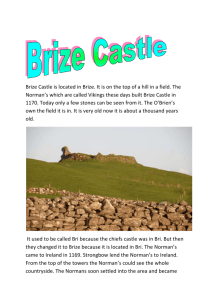

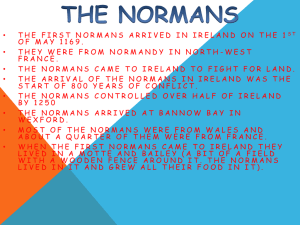

The Normans: Monty's Proud Ancestors? By Michael Wood Field Marshal Montgomery's view of the Normans was coloured by his own ancestry - but others see England's conquerors in a much less rosy light. Michael Wood attempts to see both sides. 1066 revisited Here's a personal take on the myth of the Saxons and the Normans. When I was at school in 1966, the 900th anniversary of the Norman Conquest was celebrated with much broohaha. On television, pundits tramped over the battlefields of Hastings and Stamford Bridge. Early in the year, The Sunday Times published an essay in its colour supplement by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, the British war hero of El Alamein and D-Day. Montgomery's position on Anglo-Saxon England was essentially that of Thomas Carlyle. 'Without the Normans, England would have been nothing: nothing more than a small island on the fringe of Europe, inhabited by tribes of Jutes and Angles wandering around in pot bellied equanimity.' 'In Monty's view it was a victory of ... forward-looking Europeans over backward-looking provincials ...' In other words, the Anglo-Saxons were long-haired backwoodsmen whose achievements were as nothing till the Normans brought discipline, organisation and European civilisation. To 'Monty', a military man, the Battle of Hastings was proof of it. Just think of Harold's absurd strategy and non-existent tactics - charging all that way from Yorkshire to Sussex only then to stand on a hill and be cut down, pointlessly resisting, while the Conqueror's New Model Army, with their regulation haircuts, wheeled on horseback in parade-ground precision and jabbed them to defeat. In Monty's view, it was a victory of new technology over old, of forward-looking Europeans over backward-looking provincials who had probably stayed up all night quaffing flagons of ale. Letter to Montgomery Sitting in my history class next day I was so furious that I decided to pen a reply. Struggling to find the right tone, I eventually hit on writing, in the first person from King Harold, a defence of my beloved Anglo-Saxons. The piece was published, and by return of post, Montgomery summoned me to come down and 'debate' the matter with him in the House of Lords. The 'debate', if such one may call it, was a damp squib, of course, but what was fascinating was what it revealed about the historical myths that we all create for ourselves out of history. We imbibe these myths, based on historical information that is sometimes true, sometimes highly coloured, as children, add our own ingredients to the mix, and then they stay with us as adults. 'The Conquest was a great boon to this country. It welded together the nation ...' Monty had plenty to say: 'Now about your piece in The Sunday Times ... before the Normans the English had no real civilisation: they had been living in the Dark Ages after all. They had had some good leaders: Alfred the Great, for example, he was a good chap. When he made peace with the Danes it was a great act of statesmanship.' 'But the Normans brought ordered government. Look at the Domesday Book. Ordered government, you see, is the basis of freedom. The Conquest was a great boon to this country. It welded together the nation; it set it on the road to empire and the world influence it has had.' I stammered a reply, blushing furiously, listing the Anglo-Saxon achievements in art, poetry, coins. But he would have none of it: 'You see, my boy ... the point is, the greatness of England would never have been possible without the Normans.' Monty was a Norman It was evident we were not going to see eye to eye. Then, looking at him over the table as he spoke, I suddenly twigged. Monty was a Norman himself. The Field Marshal's far-distant ancestor, Roger of Montgomery, had commanded one wing of the Norman army at the Battle of Hastings, and his reward from the grateful Conqueror was a vast tract of the Welsh borderland which had once belonged to English 'thegns'. There Roger founded a Norman new town to be the centre of the shire which was to bear his own name Montgomeryshire (now called Powys). To keep the people under his thumb he studded the place with castles, even though he probably spent more time on his estates in Normandy or safe on the south coast of Sussex. 'From that moment, as far as I was concerned, Monty would always be a Norman.' Monty, of course, still bore his name and still carried his flag. And that explained his take on the Conquest. For though he was as English as I was, he saw himself as a Norman - and that's what counts when it comes to matters of identity. As for me, well, the Field Marshal may have been a national war hero, but for me World War Two was far away and long ago, much longer ago than 1066. From that moment, as far as I was concerned, Monty would always be a Norman. Looking back on it now, I realise of course that I was as much prey to my own history myth as Mongomery was to his. It had been created not only by the historians I'd read (Frank Stenton among them), but by the children's books, the comics, the paintings in the Town Hall that I had been exposed to as a child - all filling my head with images and tales that had sunk in long before the facts and sources had become an object of any scholarly inquiry. And Monty saw it all from the Norman side. So there we were in 1966, still bending or ignoring the historical facts to fit our personal myths. For both of us, I daresay, it was a matter of belief rather than knowledge. And, needless to say, that is not the way historians are supposed to think. Roger of Montgomery William Blake says that any fool can generalise, the real art is to be particular. And that's especially true of history. In history it is all in the detail - you learn things from the particular. For example, some time after my brush with Field Marshal Montgomery all those years ago, I was making a film about the Norman Conquest for the BBC. I was looking for individual characters, a real-life Ulric the Saxon, for example, or a real-life Norman knight. I decided to go looking for Monty's ancestor, Roger of Montgomery, as an example. We went back to his ancestral village in Normandy, to see his estates there. Then we went out to the Welsh border, to the town that still bears his name. Go there today and you will still see a big stone Norman castle on the hill which stands over the town. It was built to control the Welsh border and the trade ways into England. A mile or so away beyond the fields is the site of the original castle, built by Roger in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Hastings, when the Norman army fanned out to suppress the English resistance and clamp hold of the country. '... the archaeologists compared them to SAS men, in chain mail from head to foot ...' The place is called Hen Domen. It was a motte and bailey castle, with great ditches and a huge mound on which the inner castle was built of great wooden timbers ringed by palisades. It was also the site of the only long term systematic archaeological dig of a Conquest-period Norman castle. Here, if anywhere, we might get evidence from the ground of what it was like at the time of Roger of Montgomery. Standing on Hen Domen, in the company of the archaeologists, I thought back to those first months after the Battle of Hastings. The Norman army took the submission of the English nobility in London, but out here they still had to impose their will on the people. After they had laid out the perimeter of the castle, the landscape for a mile around it was blitzed, so there were no trees or bushes left for the resistance to hide behind. Then in the middle of it, massive earthworks were thrown up by captured English labour, to be crowned with great timber palisades, towers, gates and fighting platforms. Inside was crammed with mess huts, stables, latrine blocks, armouries and forges to supply munitions. As for the men who used it, the archaeologists compared them to SAS men, in chain mail from head to foot, their steel helmets with great nose pieces and their heavy weaponry. Many of them were mercenaries - violent men, men who couldn't care less what they did to the native people, practised killers who were in it for the money. Perhaps that is an imagining too far. But what the archaeologists could show was that this was a place made purely and simply for war. Oppressing the poor Hen Domen was just one castle out of many hundreds that were built across England at that time. It was a custom-made base with prefabricated buildings from which heavily armed mounted parties could go out to terrorise, to burn and to take hostages. Thinking of the postholes, the blackened smelting pits and the heaps of sling shots, I began to imagine what it had been like in those days when, in the laconic words of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicler: '... the French had possession of the place of slaughter, because of the nation's sins.' No wonder they felt that. It also says in the 'Chronicle': '... they oppressed the poor people by building castles everywhere.' And the chronicler Simeon of Durham tells the tale of the Northumbrians reduced to selling their children into slavery: 'They were left to eat rats and grass.' '... it was the Anglo-Saxons who created England.' That's the world of the Norman Conquest - the dismantling of a beautiful and rather archaic older civilisation by a younger and tougher one. The conquerors were gifted too, no question, but were more brutal than those they disposessed. Politically, as Frank Stenton said, they were masters of their world. They initiated England into the mainstream of European culture. They left great monuments - gigantic cathedrals, huge castles, the Tower of London. But we always have to remember that these are the works of the conquerors. 'What had it been without them?' Thomas Carlyle asked. Of course we don't know. What we can say, I think, is that it was the Anglo-Saxons who created England. It was left to the Normans and their successors to create Great Britain, and they did not succeed so well. Theirs is the political legacy we are attempting to deal with at the beginning of the 21st century. About the author Michael Wood is the writer and presenter of many critically acclaimed television series, including In the Footsteps of...series. Born and educated in Manchester, Michael did postgraduate research on Anglo-Saxon history at Oxford. Since then he has made over 60 documentary films and written several best selling books. His films have centred on history, but have also included travel, politics and cultural history.