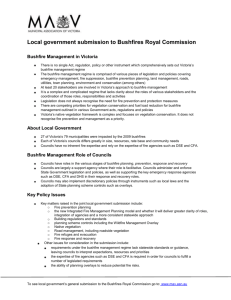

Guide to managing environmental risks in fire management in rural

advertisement