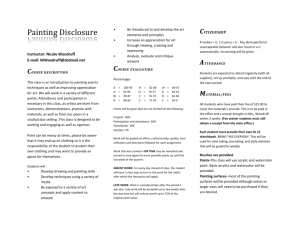

Tainted by Reality

advertisement

Tainted by Reality By Julia Marsh Painting for me was like creating another world. The world we live in is flawed, harsh, and unforgiving. The worlds I created were not so. And now, standing in my own, already-cluttered-enough studio, stood a reporter. This thin man was around forty years old. He was tall and had a dark thin moustache. His black hair, coming out from under a derby hat, was shoulder length and pulled back into a pony tail. He wore an old suit. Around his neck hung a manual film camera, and in his hand was a pad of paper and a small pencil. And he refused to let me do my work without distraction. “I just want to write a small feature for our local section this week. You’ve sold multiple works of art to our townspeople.” “I have.” “Why don’t you tell me more about your childhood and adolescence?” the reporter insisted. “Where did you grow up, go to school…?” He walked about the studio, snapping pictures of my work. “I grew up in Murat,” I told him, “just a few hours south of here. I – please be careful!” The reporter moved a piece of my pottery, which always made me nervous. He held it as he took a closer look at the painting which had been obscured by the object in his hands. “I went to school in the Murat school district, and finished in 1937.” “1937, you say?” He made a mark with his half-pencil on his pad of paper. “That was not too long ago! What was your ranking in your graduating class?” “I finished as a ninth grader,” I told him. He gave me a weird look, which I was used to. Not graduating always got me some disrespect, which is why I always preferred to be indoors, avoiding social gossips and painting and creating. I still hated the shocked looks I got. Most men were no smarter than I was, even with a degree! “You see, the school system wasn’t the best for my education. I couldn’t take tests or work on teams. My best work was individual. I had always considered myself to be bright enough to become a successful businessman, with a large house and a lovely wife who would model for my artistic endeavors from time to time…” I doubted that was enough detail to convince the reporter and potential readers that I was indeed educated enough to carry on a social status as a citizen. “I should say that even my own parents, who had a close eye on my schoolwork, would consider me a bright young man. But the School didn’t, so I quit high school. That’s when I began to paint, you see.” The reporter tried to cut in, but I continued, wishing to promote my works when I got the chance. “I’ve painted portraits, landscapes, imaginary worlds, you see them all here. I’ve painted entire books on a panoramic canvas. I’ve done murals. I’ve thrown pottery and pieced cloisonné, I’ve chiseled sculptures. I consider myself to be right along there with Vincent Van Gogh and Claude Monet. I’m sure you’ll agree.” “I… I see.” I put down my brush, wiped my hands on my apron, and leaned in toward the reporter. “What else can I tell you?” “Some people have alleged that you really do not deliver the quality artwork you claim to be able to create. They’ve paid you for portraits and you’ve given them nothing worth displaying. Can I get a comment?” I was utterly flabbergasted. “Nothing worth displaying? Are you insinuating that I cannot paint?” “Most certainly not,” the reporter assured me in defense. “I was simply quoting others.” “Well, kind sir, you can tell those others whom you have quoted that I am every bit as good as I claim to be. The beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Any more questions?” I asked impatiently. I was tired of these pointless accusations and wished to get back to my current creative endeavor. “Um… Are you married?” My one question remains: What does marriage have to do with an artist at all? I hated speaking of the woman. “Oh! Um…” I searched the room for an escape from the question. I was married to an average woman – one who may taint my professionalism if I brought her into the equation. I pushed my glasses up on my face. “Have you seen that work, there, a foot to your left?” What a smooth change of subject. The reporter looked to his left and saw one of my greatest works. It was a small ceramic model of our dog, Pal, painted with brown and golden splotches of paint. “That is an original work of mine,” I told the reporter. It’s a ceramic sculpture of our dog. He’s a bit fluffier in reality, but clay can be a fickle thing. Hard to really portray textures.” “Sir?” I stopped talking and looked over my glasses at him. “Are you married?” he repeated. “Yes,” I told him plainly. “Do you wish to share any more detail with the Toulouse Daily Herald?” “She is clingy, pretty, and kind. She is not beautiful, or extravagant. There is not much more to know. If you wish to talk to her, she is in the kitchen, cooking my dinner.” I pointed with my paintbrush to the other side of the room where the door was. “Through that door.” The reporter nodded, then asked, “May I get a picture of you at work?” “Of course.” I posed in front of my canvas, halfway through my painting, with my paintbrush poised for the next stroke. The flashbulb went off, I smiled, shook the reporter’s hand, and he walked through the door to speak with my wife. I continued to paint my next masterpiece-in-progress. I loved entering into the world of paint. Really, I loved entering into the world of art in general. I had accumulated quite the assemblage of masterpieces. Some I sold, but I never felt fulfilled, and this I attributed to the fact that I was never rich. Had I been rich, I would have had any woman I wished to have, in a brilliantly decorated maison in the heart of Nice, with all the things my heart desired. That was what I had always hoped for but never achieved. The most important to me among these pleasures I had hoped to attain was a lovely wife. I had imagined a dark, mysterious beauty, not unlike the ones on the cover of L’Artiste Magazine, to paint upon my leisure. She would have laughed at my jokes, lounged in my studio playing some instrument, read to me, and made love to me when I was not busy with my art. She would have been perfect. Instead, I found an average, clingy, uncreative wife who only had her cooking skills and the art of words. She had written me notes, cooked me dinner devotedly, and cleaned the house for five years now, but those were not attributes I would have searched for intentionally. She was fine, but not what I had dreamed of. Then there was the matter of the living space. I don’t know why I expected a grander house, but I did. I imagined a Victorian house overlooking a lake, with a pier to sit on and a sunset to admire. Instead, I lived in a cabin of a house, next to a creek and some woods. Here, I was confined to a small studio, no larger than 13 feet in either direction. It was too cozy and too converging. There was a glass sliding door on one wall, which led to a small balcony facing an expanse of woods behind our house, which could from time to time provide a landscape for my painting. However, the deer were constantly distracting me, and the trees blocked the last of the sun’s rays, disabling me from painting a proper sunset. It was all subpar. The next day, I sat painting in a sleepy sort of haze. I’d been working on the same detailed painting for some time now, and I was ready for a nap. The current painting I was working on was one of a businessman and his wife. I had modeled the man after myself, for I had always hoped to be affluent in that area of work. The man in my painting, however, was much better-dressed. He wore a three-thousand-dollar suit, a gold watch, and sleek glasses. His hair was neatly combed and his beard clean-cut. Behind him in the painting was a dark-haired and bronze-skinned woman in a glamourous dress, leaning against a baby grand piano. The two were, no doubt, the classiest people a person could make acquaintance of. Yesterday, I had finished the background in the painting and had begun working on the woman. Today, I began to mix paint for her hair and skin. I could see the gorgeous brown of her skin before I began to paint, as if the white of the canvas couldn’t truly hide the portrait beneath its surface. It was my habit to sketch on the canvas before I painted, but the grey of the graphite couldn’t hide the color beneath the surface. As I touched my brush to the canvas to fill in her face, a knock came at the door. I welcomed in the visitors. It was a man and a woman, and both were well dressed. The more I thought about it, the more I realized that the man and woman were very similar to the ones in the painting I was working on. Actually, they were exactly like the ones on the canvas. “Who are you?” I asked apprehensively. It couldn’t be, I thought. “This is my wife, Bea,” the man answered me, and his wife curtsied and smiled at me. “And your name?” I asked him more directly. “I am who you have always hoped to be,” the man replied. I stared at him for a minute. His wife began to take a turn about the room, admiring my artwork. “So,” I began again, hoping to shed some light on the strange situation, “What is your line of work?” “I am a businessman, plain and simple,” he told me. “I travel among different companies, offering my expertise in any area they may desire. I find it to be a satisfying job, but it is hard work indeed. It pays off though, good friend. I’ve got all the gold I desire.” He laughed heartily. I smiled noncommittally. “And how is your lovely wife?” “All the beautiful lady has are her tempting looks. Can you believe it?” he asked me. “I once asked her how she thought my personality was, and she said she never thought on such things! She sits alone most days, pleasing to the eye and ear as she plays the piano, but nothing more, good friend.” Suddenly the door to the kitchen opened and my wife walked into my studio. She smiled and handed me and the two visitors a glass of wine. Once we had all taken a sip, she said, “Anything else gentlemen? Madame?” “No,” I said, “that’s quite well, thank you.” She nodded, curtsied, and went back into the kitchen. “Here I am going on about my own lot, when you’ve got quite something yourself. Are you married?” said the businessman. That question kept coming back like a bad penny. And now a businessman, whom I wanted very much to impress, was the one asking. I decided that it was no use lying or making excuses. “I am,” I said in nothing much more than a whisper. “Ha!” his loud laugh echoed through the room. “She is not the most tempting woman, is she? No, but there is something there. A willingness, you see? Her attitude of service is most admirable.” “Yes, but not what I had in mind,” I said. “You know, I had in mind quite a different world myself! This cabin of a house is too cozy, too converging. I need space for my work, you see? Painting in such a miniscule studio is not what I imagined. I imagine a Victorian house overlooking a lake, with a pier to sit on and a sunset to admire. Here, the trees block the last of the sun’s rays and the deer are constantly distracting me. You see? Grandiosity is what I lack!” “The businessman nodded thoughtfully. “But your wife, sir, your wife!” “My wife,” I said, “is not much compared to what I expected. All she’s given me is this note and some dinner each night.” I glanced at the note on my table that my wife wrote a year ago. “I expected a woman like yours – one I could sketch in my free time. With skin of bronze and hair of polished leather…” “A note?” said the businessman. “May I?” “Of course.” He picked up the note and read aloud, “My dear,” he paused and winked at me. I rolled my eyes. “How great an artist you’ve turned out to be. I cannot convey how entertaining it is to watch a plain slate of canvas be pulled aside by your brush, opening the window to a wonderland of color and imagination. Quite a poet you’ve found yourself, eh good friend? This note must be quite an encouragement!” He laughed. I laughed, too, but at his ignorance. “This note gives me only a small sense of accomplishment. What tangible accomplishment does my wife really give, though? Nothing.” He was not bothered by my opposition. “Nonetheless, good friend, I’d trade you wives in a blink! My life may be comfortable, but I’m not being served as a man ought to be!” I was shocked. “But are you not content with the money you have? And with the beautiful wife you have? Pardon me for this, sir, but you seem belligerent against your comfortable life. I failed when I tried to be someone like you. I wanted what you have – the wife, the job – so how could you not appreciate it?” He looked at me, with a look on his face I could not quite read. “It is simple, good friend,” he said. “Your depth and your character kept you from being a successful businessman. You cannot cheat people out of money, that’s your problem.” I’m sure I had a blank look on my face. What could he have meant? Businessmen have depth, character, and honesty. He glanced at his watch. “Ah, good friend, I must be going! I’ve got a conference in forty minutes and a presentation to prepare before then! Have a good day.” He reached for his wife’s hand, and she followed him out the door. I sat at my easel and stared at the painting I was halfway through painting of the man who was just in my house. I leaned over, resting my elbows on my knees and sat there a minute, thinking, with my eyes closed. I didn’t understand why the man seemed so belligerent, so ungrateful. I opened my eyes. I was so exhausted. I stood up and walked over to the kitchen door. I opened it and peeped my head in. My wife looked up from her cooking at me. “Dinner is almost ready, darling,” she said. “Tell me, what did you think of our guests?” “Our guests?” My wife looked confused. “Yes, the man and the woman. Did the man seem like the sort of husband you’d like to have one day?” She laughed. “Honey, I have no clue what you’re talking about! Were you daydreaming again?” She winked at me. And then I realized that of course portraits could not come to life. I had been dreaming. I shut the door and walked back over to my easel. The businessman’s words still rang in my ear, as real as the wildlife noises coming in through the back door: “You cannot cheat people out of money, that’s your problem.” I grunted. “Trade wives, ha! Cheat people? I can be a good businessman without all that!” I was bothered that the businessman in the painting, the man of my dreams, was so flawed. I decided to be done painting him. I grabbed the canvas and brought it over to the trash bin. I held it poised, taking one last good look at my halfway-masterpiece, now tainted by reality. But another reality struck me. “A good businessman wouldn’t waste such a canvas,” I muttered to myself. “To waste a €50 canvas would be fiscally irresponsible!” I brought it back to my easel and began to touch it up where my fingers had smudged the background. “More reality! Depth! That’s what this needs!” And I continued to paint. “Dinner, dear!” my wife said from the kitchen. I didn’t respond. I was so intrigued by this new idea – almost a separate reality – of the man I could be if I simply dreamed more…tried harder. I dipped my paintbrush into the new deep red that would color the woman’s dress.