School Safety Initiatives in the US

advertisement

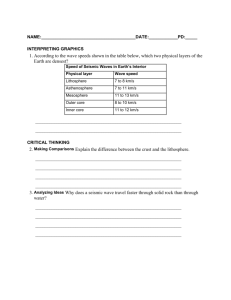

School Safety Initiatives in the U.S. Marjorie Greene Earthquake Engineering Research Institute Oakland, California, USA This paper will briefly review the status of school safety initiatives in several states in the U.S. with high seismic hazards, and then focus a bit more on school safety programs in California, which has a longer history of legislation regulating school safety than other states. The paper will close with a brief discussion of the federal initiative to promote incremental retrofit of schools. Brief review of school safety initiatives In the U.S., public schools are overseen by school districts--governing bodies at the local, community level. Education is not mentioned in the Constitution of the United States, and is not directly regulated by the federal government. Some states have a statewide school system, while others delegate power to county, city or township-level school boards. This means that the seismic safety of schools is regulated differently, depending on the district and/or the state. In California, the state with the most developed seismic safety program, individual districts regulate curriculum and classroom activities, while the state oversees the construction of all public schools. School safety can generally be divided into several categories—the preparedness status of students and staff through earthquake drills and exercises; the performance of non-structural components in a school building—light fixtures, furnishings, HVAC systems; and the performance of the structures themselves. This paper and presentation focus on structural performance, which, if not assured, can make moot any preparedness and non-structural improvements. Several states with high seismic risk, in addition to California, are developing school seismic safety programs. For example, scientific advances in understanding that a Cascadia subduction zone earthquake is imminent in geologic time prompted the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries (DOGAMI) and the Oregon Seismic Safety Policy Advisory Commission (OSSPAC) to develop sound public policies to forward the goal of mitigation of statewide risks (Wang and Burns 2006). As a consequence, the state has developed a school safety program that includes a rapid visual screening of public schools and other public buildings to assess their likelihood of collapse during a very severe earthquake. Five key parameters were assessed, including the seismic zone, the building structural type, building irregularities, original construction type and soil type. The reports made for each building are available online. Of the 2182 K-12 school buildings that were assessed using the Rapid Visual Screening process (based on FEMA-154), 274 were ranked as Very High Seismic Risk and 744 were ranked as high risk (Oregon Department of Education 2011). The state has developed a grant program to retrofit public buildings, including public schools. Two key elements contributed to the success of this program-Oregon State Senator Peter Courtney, who championed legislation requiring all public schools and emergency facilities to have life safety standards and the citizens of Oregon, who voted to change the Oregon Constitution Articles, which now allow state general obligation (GO) bonds to pay for earthquake rehabilitation of schools and emergency facilities (Wang and Burns 2006). In another western state, Utah, a recent rapid visual screening and study by the Utah Seismic Safety Commission identified that the majority of Utah schools may be potentially unsafe in the event of an earthquake and do not meet federal seismic safety standards. Utah sits directly on the Wasatch fault, so the risk can be significant. Using the rapid visual screening technique, engineers surveyed 128 Utah schools. According to one of the engineers involved in the project, the rapid visual screening is the first step in categorizing which buildings might need further study. Of the 128 schools sampled, 77 did not meet the necessary seismic standards and need to be further evaluated to ensure they are safe (Universe 2011). The Utah Seismic Safety Commission has proposed a bill for the last five years that would provide some funding for more detailed evaluations of these buildings. One other area of North America with a major school safety program is the province of British Columbia in Canada. The provincial government has made a 15-year, $1.5-billion commitment to make schools safer in the event of an earthquake. British Columbia is the first province to undertake a comprehensive school seismic upgrading program. To date, 121 seismic upgrade projects are complete, under construction or proceeding to construction. To date the province has spent more than $581 million on seismic upgrading of schools in 37 districts. As part of the Province’s School Seismic Mitigation Program, boards of education assessed schools in 2004 to confirm the seismic risk and scope of required projects in their districts. Project engineers used retrofit design concepts in the risk assessments that were developed by the Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of BC (BC Ministry of Education 2011). Experience in California The origins of the Field Act California has the longest history of legislatively regulating the design and construction of public schools, building on experiences from two damaging earthquakes—1925 in Santa Barbara and 1933 in Long Beach. As noted by Olson (2003), the M6.3 event in Santa Barbara was the first earthquake that resulted in significant policy changes in California, specifically the first earthquake components in building codes, in the cities of Santa Barbara and Palo Alto; the introduction of new, although optional, earthquake components in the 1927 Uniform Building Code; the endorsement by the state chamber of commerce of the idea of a statewide building code; and the emergence of professional organizations with a major interest in earthquake design. While progress in these areas was slow, it did lay the groundwork for more major changes that resulted after the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, which also registered M6.3 and caused a significant amount of damage. So the period between 1925 and 1933 “constituted a kind of transition period when recognition of California’s earthquake risk was slowly overcoming resistance and often virulent denial” (Olson 2003: 115). The Long Beach earthquake occurred in the evening of March 10th, 1933, so thankfully no schools were in session. It was immediately apparent that the state had dodged a bullet in terms of potential deaths and injuries to children, as the earthquake destroyed 70 schools, caused major damage to 120 schools and minor damage to 300 schools (CSSC 2004). The earthquake marked the beginning of the “modern era” of seismic safety in California for building codes, state laws, design and engineering practices, research, instrumentation, and political activism (Olson 2003: 117). While there had been some discussion in state circles of school building safety, particularly after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake (U.S. Department of the Interior 1917, quoted in Olson 2003), no action had been taken to improve school construction until after this 1933 event. A California legislator, Don C. Field, moved quickly after the March 10th event, introducing Assembly Bill 2342 on March 23rd, as an “act relating to the safety of design and construction of public school buildings, providing for regulation, inspection and supervision of the construction, reconstruction or alteration of or addition to public school buildings, and for the inspection of existing school buildings defining the powers and duties of the State Division of Architecture. . . .[from The Assembly’s Final History of the 1933 Session, quoted in Olson 2003: 118]”. The state legislature enacted the Field Act within one month of the earthquake, setting in motion a regulatory framework that is guiding much of the progress in seismic safety in California. Although the Act passed during the Great Depression, there was support for it because: 1) public schools are funded with public money; 2) schools house the children of the electorate; and 3) the state constitution requires children to attend schools, the state is liable and thus responsible for protecting children and staff from injury in public schools grades K-12 and community colleges, and for protecting the public’s investment in school buildings during and after earthquakes (CSSC 2004). The Field Act provides for establishment of a procedure to be followed in the design and construction or alteration of public school buildings. It has been updated several times, but the following principal provisions and procedures have not been changed (DGS 2002:4): The Division of the State Architect (DSA) has the authority to approve or reject plans for construction of all new school buildings and for the reconstruction, alteration, or addition to existing school buildings for the protection of life and safety and to resist future earthquakes insofar as possible. Required plans, specifications, and estimates are to be prepared by a Californialicensed architect or registered structural engineer. The application, drawings, specifications, geologic report, and calculations are submitted to DSA for review. The documents are marked to ensure compliance with the current building code and returned to the architect. California-registered structural engineers provide the review of the structural aspects of the design. After corrections are made and back-checked by DSA, the documents are stamped for identification. When DSA receives copies of the stamped documents, the application is approved and a letter is sent to the school board indicating approval. No construction contract may be let before the approval of the construction documents is issued by DSA. Competent, adequate, and continuous inspection is required during construction by a qualified, state-approved inspector to verify that the work has been executed in accordance with the plans, specifications, addenda, and change orders approved by DSA. Visits to the construction site are required of the design professionals, who are required to observe the construction as it progresses. DSA structural engineers also visit the site to observe the construction and ensure the inspection is comprehensive. The architect and registered engineer, the inspector, and the contractor must each make a duly verified report to DSA indicating that the work has been performed and the materials have been used and installed, in every important respect in compliance with the approved plans and specifications. When all the final verified reports indicating conformance with the approved documents are received by DSA, a letter of certification of compliance with the Field Act is issued to the school board. Any person found to have violated any provision of the Act or to have made any false statement in any verified report is guilty of a felony. Seismic Safety Inventory Over the years, while there is recognition that schools in California are generally the safest in the country and have performed relatively well in recent earthquakes, there is also the acknowledgment that it is continually necessary to examine the conditions of schools, particularly in light of improved understanding of building performance and changes in building codes. In 1999, legislation was passed in California requiring the Department of General Services, through its Division of the State Architect (DSA), to conduct an inventory of public school buildings that are of concrete tilt-up construction and those with non-wood frame walls that do not meet the minimum requirements of the 1976 Uniform Building Code (UBC). Substantial improvements in the seismic design of buildings were incorporated in the 1976 UBC and were adopted for the design and construction of public schools in 1978 (DGS 2002). The Division of the State Architect developed a seismic safety inventory methodology, building from FEMA-310’s seismic evaluation procedures. This allowed DSA to evaluate buildings in a meaningful way without conducting costly field investigations. This screening process eliminated all but 16,000 school building construction projects, and these projects were then evaluated using a construction documents review process to identify the lateralforce resisting systems (DGS 2002). Based on this review, 9,659 buildings (92 million square feet) were identified as non-wood frame and built before July 1, 1978. These buildings were then classified into one of two seismic vulnerability categories (DGS 2002): Category 1: those building types that are likely to perform well and are expected (but not guaranteed) to achieve life-safety performance in future earthquakes Category 2: those building types that are not expected to perform as well in future earthquakes as Category 1 building types and that require detailed seismic evaluation to determine if they can be expected to achieve life-safety performance. Figure 1 below shows the amount of square footage that falls into these two categories, along with wood frame construction that was not part of this study. Individual school districts can choose to evaluate and upgrade their buildings; there are continuing discussions in the legislature about providing funding support for those districts that are otherwise unable to undertake such work. Figure 1: Public school buildings in Categories 1 and 2 Private school initiatives Private schools in California are not required by law to meet Field Act standards, and are therefore unlikely to be as safe as public schools of similar age. No survey has been done for private schools. If private school buildings pose a risk to life-safety of their students, it is difficult to assess because of lack of information about historical regulation and enforcement during the design and construction of these buildings (CSSC 2004). Unlike Field Act schools, there are also no regulations covering the anchoring and bracing of the contents of buildings installed after construction is complete. Table 2 below summarizes some of the administrative differences between the Field Act and the Uniform Building Code, which is the code regulating private schools. Table 1: Summary Differences Between Field Act and UBC Field Act Title 24, CCR for Public Schools Administrative Requirements Design Professionals An architect or a structural engineer must be in general responsible charge of the design and construction Plan Approval Process Requirements for submitting the site data, geologic hazard reports, calculations, change orders are provided in detail. The process of reviewing, marking the plans, and verification of corrections are delineated. Inspection Continuous inspection by an inspector approved by DSA is required. Verified Reports The inspector is required to provide a verified report under penalty of perjury attesting that the construction is in compliance with the approved plans and specifications based on personal knowledge provided by continuous inspection. The architects, engineers, and contractors are required to provide a verified report under penalty of perjury attesting that the construction is in compliance with the approved plans and specifications based on periodic visits to the site and the reporting of others. Uniform Building Code for Private Schools In addition to an architect and structural engineer, a civil engineer is also allowed to be, in general, responsible charge of the design and construction. Detailed requirements are not provided. Periodic special inspection at construction milestones (i.e. before concrete placement, before covering structural framing, gypsum board inspection). No similar report is required. No similar report is required. Recent Initiative in City of Berkeley The City of Berkeley is an example of a community that worked together to reduce seismic hazards in its schools. Prompted by the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, the community of a little over 100,000 residents worked together to address the seismic risk in its 16 public schools. After the 1989 earthquake, a group of concerned parents approached officials with their concerns about the safety of the schools built in the 1950s and 1960s with concrete. The parent advocates were appointed to serve as an advisory body to the school district. The discovered engineering reports issued ten years earlier that confirmed that at least one of the schools, still in use, was unsafe and was to have been closed. The materials had been misplaced by school officials and never acted upon (Chakos 2004). The parents convinced the district to review all the schools again, eventually learning that 7 of the 16 schools posed serious life safety risks. Once the school district determined the extent of the risk to so many of its buildings, the city’s state legislators also took action, sponsoring state legislation that enabled the school district to tap into state emergency funds. Several years into this process a larger community advisory group recommended that the school district embark on a comprehensive safety program, totaling $158 million, to rebuild all the schools. In addition to finding federal and state funds, the community ultimately approved a total of six special hazard mitigation taxes over a ten-year period. Since 1992, all the public schools in Berkeley have been rebuilt (Chakos 2004). Experience of Calexico, California In April 2010 a M7.2 earthquake struck Baja California Mexico and Southern California, with the epicenter located close to the town of Calexico. At a recent school safety workshop, the school superintendent for the Calexico schools described the experience that her 9300 students and 13 schools went through (Luna 2011). Most of the schools were closed for between 17 and 23 days because of content damage that included hazardous materials— broken lights, science lab materials, ceiling tiles, floor tiles, paint, mercury, lead and asbestos. Debris removal, clean-up and repair also necessitated school closures. In some cases repairs were completed more than once, because of continuing damage associated with aftershocks. Windows continued to break and pipes broke, even after the schools were reopened. In addition, damage associated with the initial earthquake to steel beams was not discovered until weeks after the event, necessitating closure of some buildings. The experience of this school district highlights the importance of addressing non-structural components as well as structural safety Federal Initiative—Incremental Retrofitting Recently, the federal government through the Federal Emergency Management Agency has developed guidance for school districts around the country in seismic regions that encourages incremental retrofit of school buildings that might not meet high seismic standards. The incremental approach reduces earthquake vulnerability at the most cost- effective time in the building life cycle, by combining seismic retrofitting with other related work that is already being done. FEMA has prepared a document, FEMA-395, that provides a framework and information for managing school earthquake risks in such a way. The major goals of making schools more earthquake resistant include: To provide safe buildings for children and staff To maintain public education To provide emergency shelters To avoid major disruption to community life (Mahoney 2011). Advantages to incremental retrofitting are highlighted in Table 2 below: Single-Stage Retrofitting All costs are concentrated in a short time period Construction is disruptive to school operations Requires temporary space during construction to house displaced students and staff All seismic vulnerabilities are mitigated in a single phase of work Seismic retrofitting work is generally performed independent of future maintenance and remodels Incremental Retrofitting Costs are distributed over multiple fiscal years Construction can be phased to occur during summer breaks to minimize disruption to school operations Students and staff are not displaced Seismic vulnerabilities are mitigated in a phased approach, beginning with the most severe vulnerabilities first Seismic mitigation can be integrated with other scheduled maintenance and remodel projects Summary School seismic safety in the U.S. is recognized to be of increasing importance, although to date only a handful of states have developed active seismic retrofit programs. California has the longest and most comprehensive history with school seismic safety, but even in that high risk state there are many challenging issues with funding and political priorities. FEMA’s initiative with incremental retrofitting may be one future approach that offers opportunities to more schools to conduct evaluations and retrofits over time. References B.C. Ministry of Education. Seismic Mitigation Program (2011). http://www.bced.gov.bc.ca/capitalplanning/seismic/ Accessed March 10, 2011. California Seismic Safety Commission (2004). Seismic Safety in California’s Schools Findings and Recommendations on Seismic Safety Policies and Requirements for Public, Private, and Charter Schools. December. Sacramento, CA: CSSC. Chakos, Arrietta (2004). Learning About Seismic Safety of Schools from Community Experience in Berkeley, California. Keeping Schools Safe in Earthquakes. OECD. Department of General Services (2002). Seismic Safety Inventory of California Public Schools (A Report to the Governor of California and the California State Legislature). November 15th, 2002, Department of General Services. Luna, Christina (2011). April 4, 2010--Laguna Salada/El Mayor-Cucapah 7.2 Magnitude Earthquake. Earthquake Engineering Research Institute 2011 Annual Meeting. February 12, 2011. Mahoney, Michael (2011). Seismic Protection of Schools; FEMA’s Perspective. Earthquake Engineering Research Institute 2011 Annual Meeting. February 12, 2011. Olson, Robert A. (2003). Legislative Politics and Seismic Safety: California’s Early Years and the “Field Act,” 1925-1933. Earthquake Spectra, Volume 19, No. 1, February, pages 111-131. Earthquake Engineering Research Institute. Oregon Department of Education (2011). Quake Safe Schools. Retrieved from http://www.ode.state.or.us/search/page/?id=2061. 1998-2011, Oregon Department of Education. Seismic Safety Commission (2004). Seismic Safety in California’s Schools. December 2004, Sate of California Seismic Safety Commission. Universe (2011). “Utah Seismic Safety Commission: 60 percent of schools fail standards”. February 2, 2011. www.Universe.byu.edu. Wang, Yumei and Burns, Bill (2006). Case History on The Oregon Go Bond Task Force: Promoting Earthquake Safety In Public Schools and Emergency Facilities. Paper presented at 8th National Earthquake Conference, April 18-21, San Francisco, CA.