Guide-Draft_NABR_Comments_to_NIH_on_The_Guide1

advertisement

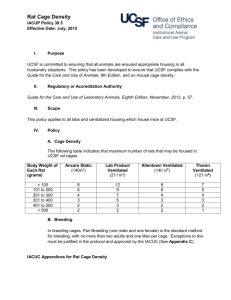

4/13/2011 Sent via electronic and U.S. Mail Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD Director, National Institutes of Health Building One, 126 Shannon One Center Drive Bethesda, MD 20892 Re: NIH’s Proposed Adoption and Implementation of the Eighth Edition of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals Dear Dr. Collins: This letter is in response to the National Institutes of Health’s solicitation of comments concerning the Proposed Adoption and Implementation of the Eighth Edition of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Guide) that appeared in the Federal Register on February 24, 2011 (76 Federal Register 10379 – 80). It is being submitted in this format because the 6,000 character limitation placed on electronic comments would not permit us to make meaningful comments on behalf of our membership. The National Association for Biomedical Research (NABR) represents more than 300 public and private universities, medical and veterinary schools, teaching hospitals, voluntary health organizations, professional societies, pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies promoting sound public policy for the humane use of laboratory animals in biomedical research. While NABR recognizes that the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals is a valuable document that aims to strike a balance with the needs of research and the welfare of animals, at this time we cannot recommend that NIH adopt the Eight Edition of Guide (new or 2011 Guide) as a basis for evaluation of institutional programs receiving or proposing to receive Public Health Service (PHS) support for activities involving animals. NABR is concerned that: (1) the 2011 Guide contains many recommendations that will, in effect, function like regulations, rather than the “guidelines” for the care and use of research animals authorized by the Health Research Extension Act of 1985; (2) there is insufficient scientific evidence for some revisions reflected in the new Guide; and (3) the additional provisions of the 2011 Guide will have a significant economic impact on PHS-assured institutions. On behalf of our institutional membership, NABR recommends that NIH not adopt the new Guide until the above concerns are addressed. We respectfully request that the 2011 Guide be reviewed for consistency with the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Bulletin No. 0702: Final Bulletin for Agency Good Guidance Practices, specifically the definitions, standards, notice and public comment provisions regarding “significant guidance document[s]”, “economically significant guidance document[s]” and “regulatory action” (72 Federal Register 3432-40). 1 4/13/2011 The Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Bulletin No. 07-02: Final Bulletin for Agency Good Guidance Practices defines the term “guidance document” as “an agency statement of general applicability and future effect, other than a regulatory action (as defined in Executive Order 12866, as further amended, § 3(g)), that sets forth a policy on a statutory, regulatory or technical issue or an interpretation of a statutory or regulatory issue.” The Bulletin also defines a “significant guidance document” as “a guidance document disseminated to regulated entities or the general public that may reasonably be anticipated to: (i) Lead to an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more…[or] …(iii) Materially alter the budgetary impact of entitlements, grants, user fees, or loan programs or the rights and obligations of recipients thereof” and an “economically significant guidance document” as “a significant guidance document that may reasonably be anticipated to lead to an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more…” In view of the Guide’s general applicability, scope, depth, complexity, and effect of setting NIH policies regarding the humane care and use of laboratory animals in PHS supported activities, it is reasonable to assume that NIH’s adoption of the 2011 Guide would qualify the Guide as a “guidance document” as defined by OMB. To follow all the Guide’s provisions in order to qualify for NIH awards, the more than 1,100 PHS-assured institutions will likely spend a minimum of $100 million annually. Therefore, we believe it is imperative for the animal research community to have a meaningful opportunity to comment on the substance of the new Guide and its financial consequences so that NIH can formulate an appropriate, well-informed implementation plan. NABR’s concerns are discussed in greater detail below along with our recommendations for future action. I. NABR is concerned that the Eighth Edition of the Guide contains substantive changes and additions to the previous edition. The limited opportunity for comment was simply insufficient in terms of both time and substance. A meaningful process for public input should be required. As indicated in the supplementary background information in the subject Federal Register notice, since 1985, the PHS Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (PHS Policy) has required that institutions receiving PHS support for animal activities base their animal care and use programs on the current edition of the Guide and comply, as applicable, with the Animal Welfare Act (AWA) and other Federal statutes and regulations relating to animal activities. The PHS Policy was authorized by the Health Research Extension Act of 1985 (P.L. 99-158; 42 U.S.C. 289d) and is incorporated by reference in a listing of “several other HHS policies and regulations” that apply to grants for research projects (42 C.F.R. 52.8 and 42 C.F.R. 52a.8). While the Guide itself is not included among the policies and regulations listed, it is specifically and repeatedly referenced in the PHS Policy. The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals has been an essential laboratory animal welfare reference document since it was first published in 1963. The 2011 Guide includes new 2 4/13/2011 and expanded coverage of the ethics of laboratory animal use; components of effective animal care and use programs (regulations, policies and principles; program management; program oversight; disaster planning and emergency preparedness); housing, environment, and enrichment for terrestrial and aquatic animals; veterinary and clinical care as well as physical plant characteristics. The 2011 edition is over 200 pages, nearly double the length of its predecessor. It contains more than 40 statements about what institutions “must” do, including 29 newly-stated requirements. In addition, there are now approximately 660 recommendations incorporated in the Guide that PHS award seekers “should” do. The 2011 Guide (p. 8) defines “must” statements as “actions that are imperative and mandatory duty requirements.” “Should” is said to mean “a strong recommendation for achieving a goal” noting that “individual circumstances might justify an alternative strategy.” The current comment process which limits comments to 6,000 characters including spaces and requires comments be submitted by April 24, 2011 is simply insufficient to provide NIH with meaningful comments as to the impact of the Guide on institutional animal care and use programs. Based upon the input we have received from our members, their comments specifically on the recommended minimum cage sizes for rodents housed in groups as well as other provisions would far exceed this limit. When the comments are requested for the Guide under the requirements of OMB Bulletin No. 07-02: Final Bulletin for Agency Good Guidance Practices, no such limits should be in place. II. There is insufficient scientific evidence for some revisions reflected in the new Guide. Excellent new reference information from the peer-reviewed scientific literature has been added to the 2011 Guide in support of many subject areas. However, scientific evidence is lacking for changes in at least one major subject, the “recommended minimum space” for animals by species (Tables 3.2 - 3.6). In the Preface of the 8th Edition, the Committee acknowledges that scientific information is insufficient when it comes to space and housing needs of laboratory species, yet still includes new recommendations that will have significant impact on the research community. While acknowledging that many variables must be considered when housing animals in the laboratory, the new Guide offers no justification from the scientific literature as to why minimum space recommendations have been changed and why specific increases in dimensions were selected. Because the minimum cage sizes are expressed in exact dimensions by species in the Guide, they amount to fixed engineering standards with which PHS-assured institutions must comply. While the 2 inch increase in the height of rabbit cages (Table 3.3) and several changes in nonhuman primate caging (Table 3.5) are a problem for some NABR members, it is the revision of minimum space for laboratory rodents (Table 3.2) that is causing the greatest concern. For the first time the new Guide indicates recommended space for a “Female + litter” for both rats and mice, specifying a floor area of 51 in2 (330 cm2) for the former housing group and 124 in2 (800 cm2) for the latter. This designation would exclude the current practice of housing rodent pairs 3 4/13/2011 (male and female) and trios (one male, 2 females) together continuously for breeding purposes in the standard cage used by most facilities. The new European Directive for the Protection of Animals Used in Scientific Procedures (2010/63/EU) indicates the same floor space requirements, but uses the term “breeding” cages for rodent pair/trio housing, thus permitting the practice of housing breeding pairs and trios in existing cages (See Attachment 1). Because the new Guide will require larger caging for standard breeding practices, PHS-assured institutions and NIH contractors will be faced with the prospect of replacing existing cages for breeding pairs and trios with larger cages. Further complicating the situation is the fact that the 2011 Guide states (p 60-61), “Floor space taken up by food bowls, water containers, litter boxes and enrichment devices (e.g. novel objects, toys, foraging devices) should not be considered part of the floor space.” There are significant operational, logistical, physical plant and financial issues associated with these recommendations, which will be commented upon in more detail by individual institutions and commercial laboratory animal breeders. This rodent breeding cage issue was raised in comments on the pre-publication version of the Guide released in June 2010. The final version of the Eighth Edition published in January of this year, only added an asterisk to the title of Table 3.2 with the related note: “* The interpretation of this table should take into consideration the performance indices described in the text beginning on page 55.” OLAW currently has a “frequently asked question” published on its website that leads us to believe that the flexibility of institutions to use performance based standards in determining a policy on cage size will be more limited than implied by the language beginning on page 55 of the Guide. The text of that posting appears below: May the IACUC approve deviations from the Guide for rodent (mice and rats) cage density? - OLAW supports the Guide’s approach to applying performance standards to achieve specified outcomes, and expects institutions to use the Guide’s engineering standards as a baseline. The Guide clearly states that the need for adjustments to the recommendations for primary space enclosures should be made at the institutional level by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and should be based on performance outcomes. The Guide further identifies examples of performance indices to assess adequacy of housing, including health, reproduction, growth, behavior, activity, and use of space (Guide, pages 25-26). IACUC determinations of the need for adjustments in the space recommendations should be based on veterinary considerations or scientific justification relative to the nature of the protocol and its requirements. Blanket, program-wide deviations from the Guide for reasons of convenience, cost, facility capacity, and other non-animal welfare considerations are not acceptable. IACUC approved deviations from the Guide must be clearly documented and reflect the scientific or veterinary justification relevant to the action. For example, the Guide notes that space allocations should be reviewed and modified as necessary to address individual housing situations and animal needs such as prenatal and postnatal care. One way to address housing for maternally dependent litters of mice and rats is to consider them as single entities with their parent(s) until the pups begin actively moving about the cage, at which point multiple parental/litter groups should then be housed according to housing conditions recommended in the Guide. 4 4/13/2011 III. Adoption of the new Guide as planned by OLAW is likely to have a significant economic impact on PHS-assured institutions. Given the fact that research institutions are already under extreme financial strain and NIH faces the possibility of a significant budget reduction in FY 2011 and beyond, this economic impact must be carefully assessed. Since rats and mice are utilized as a research model by the tens of millions, the proposed change in breeding cage size is likely to have a significant economic impact that may be reasonably anticipated to lead to an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more and would also materially alter the budgetary impact of NIH grants. Based on the input received from NABR members thus far, we are concerned about the magnitude of the following financial consequences of the new Guide. A. The new Guide will dramatically increase the cost of research animals. As previously expressed by the Laboratory Animal Breeders Association of North America in comments on the pre-publication version, the new Guide’s breeding cage requirements will have a major impact on their businesses. They estimate their total initial capital investment for changes will be $494 million. Their recurring annual operating cost is calculated to be $155 million. These dramatic increases will be passed on in the form of higher research animal prices to their research institution customers, including the NIH intramural program. PHS grants as well as the NIH budget will be affected. B. PHS-assured institutions will incur increased costs for new caging and renovation of facilities. Many, if not most large research-intensive institutions, also breed laboratory rodents in-house. Based on a NABR inquiry, one large NIH grantee indicated the cost of the breeding cage change could range from $3 million to as much as $20 million depending on how the different cage sizes could be accommodated. Another estimated a cost of $6 million for retrofitting existing housing facilities. Some additional NABR member estimates were lower. However, the most common response was that officials simply have not had time to assess the best course of action and what the resulting expenses will be. NABR’s concern is that, if even a portion of the more than 1,100 PHS-assured institutions are involved with rodent breeding, the capital investment required to continue their programs could be in the hundreds of millions of dollars. C. The new Guide will increase PHS grant expenses beyond the direct cost of laboratory animals. The cost of rats and mice will certainly increase as breeders pass on the additional cost of meeting the new recommendations for breeding cages. In addition, the per diem charged to principal investigators for animal care by PHS-assured institutions will increase. In order to meet these new recommendations, institutions will either 5 4/13/2011 need to change the existing caging systems or increase the number of cages in use, thereby increasing per diem charges. While the cost impact of addressing the many new and revised recommendations is unclear at this time, there are certain to be other costs associated with programmatic changes resulting from the new Guide that will be passed on to the investigators. D. Research capacity will be reduced. In order to comply with new cage sizes, some facilities will have no option but to reduce facility capacity. One member predicts the loss of 20-30% in breeding space capacity. NABR believes strongly that the above concerns must be addressed before the 2011 Guide is adopted and implemented by NIH. To do so, we respectfully request that the 2011 Guide be reviewed for consistency with the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Bulletin No. 0702: Final Bulletin for Agency Good Guidance Practices, specifically the definitions, standards, notice and public comment provisions regarding “significant guidance document[s],” “economically significant guidance document[s]” and “regulatory action.” We recommend that NIH re-issue a notice for public comment that permits an opportunity to provide meaningful comments so that NIH may better understand the full effects of the new Guide on the animal research community and the best manner in which to implement it. We appreciate your consideration of our views and this recommendation. Sincerely, Frankie L. Trull President Attachments: 1. European Directive 2010/63/EU Annex III, Table 1.1 and 1.2, (Official Journal of the European Union, 20.10.2010) cc Patricia Brown, VMD Director, Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare Office of Extramural Research, National Institutes of Health RKL1, Suite 3601, Mail Stop 7982 6705 Rockledge Drive Bethesda, MD 20892-7982 Sally J. Rockey, PhD Deputy Director for Extramural Research 6 4/13/2011 National Institutes of Health Building One, 144 Shannon, Mail Stop 0155 One Center Drive Bethesda, MD 20892 7