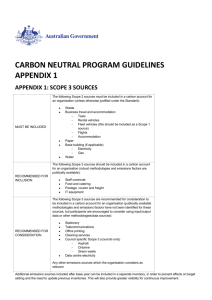

Emissions Reduction Fund Green Paper

advertisement