Jennine Ropke paper 2014 - eCommons@Cornell

advertisement

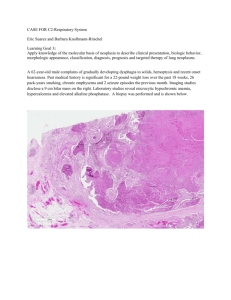

Surgical Excision and Radiotherapy of Ocular Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a Quarter Horse Jennine Patricia Ropke Clinical advisor: Dr. Luc Vallone Pre-clinical advisor: Dr. Nita Irby Senior Seminar Paper Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine January 29, 2014 Key words: squamous cell carcinoma, equine periocular neoplasia Abstract A ten year old Buckskin Paint gelding presented to the Cornell University Hospital for Animals Equine Ophthalmology Service for evaluation and treatment of an inferior lid mass and associated epiphora OS. The mass was first observed approximately one month prior to presentation and had been noticed by the owner to be increasing in size. Physical exam revealed a 4 by 4mm pink, raised, cauliflower-like mass originating from an area of unpigmented epithelium on the medial inferior eyelid. Excisional biopsy of the mass along with 1-2mm of adjacent, apparently normal, eyelid margin was performed under standing sedation and locoregional anesthesia. Radiotherapy with Strontium-90 followed without complication. Histopathology definitively diagnosed the mass as squamous cell carcinoma with incomplete excision. The patient presented again four days postoperatively with blepharospasm, epiphora, and periocular swelling OS. Ophthalmic exam revealed the cornea was fluorescein positive OS, with a 1mm superficial corneal ulcer in the ventrotemporal quarter of the cornea. He was treated with ophthalmic antibiotics and pain management and by the following recheck the ulcer had resolved. A final recheck six weeks postoperatively revealed no gross evidence of tumor recurrence. The diagnostic workup, treatment, and prognosis of this horse’s periocular neoplasia will be discussed. Case History A ten year old Buckskin Paint gelding presented to the Cornell University Hospital for Animals Ophthalmology Service for evaluation and treatment of an inferior lid mass and associated epiphora OS. According to the owner, the mass had appeared approximately one 2 month prior and had increased in size. The owner has cleaned the left eye at least once a day due to the epiphora. The horse is ridden for pleasure and is pastured during the day. Clinical Findings On presentation, the horse was bright, alert, and responsive. General physical exam revealed no signs of systemic disease and was unremarkable except for his left eye and adnexa. Present approximately 2cm from the superior lid margin, at the area of the brow vibrissae, was an approximately 2cm x 3cm area of alopecia and hyperkeratinization. Present on the medial inferior lid, on an area of unpigmented epithelium, was a small, approximately 4mm x 4mm, firm, pink, raised mass, with a cauliflower-like surface. No epiphora was evident, as the owner had cleaned the left eye before arrival to the hospital. The right eye appeared grossly normal. The ophthalmic exam revealed the horse to have no other significant concurrent ocular disease. The left lens was partially opacified by a small, faint, disc-shaped translucent cataract in the central anterior cortex, with a focal extension to the axial anterior capsule. The cataract was incidental at this time as it did not affect the horse’s vision as shown by the intact menace response OS. The retina and optic nerve were normal OD except for a small area of chorioretinal scarring adjacent to the ventral optic nerve head OD. The left fundus was not examined at this visit, as the eye was not fully dilated until after the tarsorrhaphy was performed. The horse’s penis, prepuce, and sheath were carefully examined for any gross evidence of tumors and none were found. 3 Differential Diagnosis Differential diagnoses for alopecic, hyperkeratotic lesions of the skin on a horse are limited. In this patient, trauma caused by rubbing due to irritation from the inferior eyelid mass is a likely possibility. Additionally, equine sarcoids can have this appearance and are commonly located in the periorbital region. A less likely cause due to the fact that this is a singular lesion would be a parasitic dermatologic disease, either mites or lice. This lesion was not the main focus at this appointment and therefore was not addressed further. If it were traumatic, it would resolve with treatment of the primary lesion. If it was a sarcoid, benign neglect until a later date was an appropriate treatment plan at this time. Differential diagnoses for any mass follow the CHANG scheme: cyst, hematoma, abscess, neoplasia, and granuloma. Cyst, hematoma, or abscess was unlikely due to the appearance of the mass. Granulomas such as exuberant granulation tissue occur most frequently on the distal limbs and almost never on the face. Habronemiasis cannot be ruled out at this time but is unlikely. Neoplasia is the most probable diagnosis. Neoplasias that occur commonly in the periorbital region are squamous cell carcinoma, sarcoid, papiloma, lymphoma, and melanoma. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common neoplasm of the equine eye and adnexa. Paint horses are overrepresented for squamous cell carcinoma due to the presence of unpigmented epithelium at mucocutaneous junctions. The prioritized differential list included neoplastic causes, primarily squamous cell carcinoma. 4 Surgical Intervention Based on the likely diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma, surgical excision of the mass under standing sedation and locoregional anesthesia was recommended. The horse had an uneventful removal of the squamous cell carcinoma and 1-2 mm of adjacent apparently normal eyelid margin. Care was taken to preserve as much eyelid margin as possible while attempting to achieve adequate margins for complete excision of the tumor. The mass was found to have possibly obstructed his tear duct as no puncta was visible in the inferior lid (or superior lid). An apparent duct was visualized during the removal of the mass and 7-0 Vicryl sutures were used in an attempt to secure it open. Additional 6-0 and 7-0 sutures were used to close the wound. A partial tarsorrhaphy was performed to protect the cornea. Radiotherapy with Strontium-90 followed without complication. Flunixin meglumine was administered intravenously and an eye mask was placed. He was discharged the same day and prescribed oral flunixin meglumine for two days. Rechecks The horse returned four days postoperatively with complaints of acute blepharospasm, increased epiphora, and periocular swelling OS. General physical exam revealed no signs of systemic disease and was unremarkable except for his left eye and adnexa. A sedated ophthalmic examination revealed that the cornea was fluorescein stain positive OS with a small 1mm superficial corneal ulcer in the ventrotemporal quarter of the cornea, with three to four adjacent satellite lesions that were stain negative. These lesions are presumably white blood cell 5 infiltrates running in a curvolinear band corresponding to the temporal lower eyelid curve. The anterior chamber was normal OS with no flare or cells noted. The pupil was relatively miotic compared to the normal eye. Cytology assessment of the cornea showed many white blood cells suggesting a corneal bacterial infection. It was suspected that a stitch rub could be causing the problem but the small ulcer was far away from the stitches making this an unlikely cause. It was most likely an exposure ulcer from the lid block and the procedure, even though the cornea was stain negative at the end of surgery. The location is the exact location of majority of exposure keratitis cases in the equine. Cytology assessment showed many white blood cells suggesting a corneal bacterial infection. Several loose sutures were removed or trimmed and the partial tarsorrhaphy was removed. The surgical site was healing well, with granulation tissue present. The horse was discharged for medical management at home with two ophthalmic antibiotics; ciprofloxacin 0.3% and cefazolin 50mg/mL every six hours, ophthalmic atropine every twentyfour hours, and oral flunixin meglumine every twenty-four hours until recheck. The horse returned for a recheck ten days postoperatively. The ophthalmic examination revealed the following; the pupillary light reflex was intact OD and sluggish OS due to previous atropinization. The cornea was fluorescein stain negative OU. The previous ulceration OS was resolved with very faint remnant fibrosis. There was no corneal abscess seen. The surgical site was healing as expected and was covered with healthy granulation tissue. There was no visual evidence of tumor at this time. The ciprofloxacin was continued every eight hours until the final recheck. The horse returned for a final recheck six weeks postoperatively. A brief ophthalmic exam was performed and one remaining suture was removed. There was a small area of soft 6 swelling at the surgery site but no gross evidence of tumor recurrence. No epiphora was noted at suggesting that the nasal lacrimal duct was patent. All medications were discontinued. Histopathology The surgical biopsy was submitted to the Cornell’s Animal Health Diagnostic Center for histopathology. Histologic Diagnosis: Eyelid mass, left ventral: Squamous cell carcinoma Final Comments: The eyelid is expanded by a well-demarcated proliferation of neoplastic squamous cells that focally invade the underlying submucosal connective tissue, consistent with a squamous cell carcinoma. Based on the examined sections, the mass appears incompletely excised. Prognosis Prognosis for equine periocular squamous cell carcinoma is highly variable depending on size and invasiveness of the tumor. Early recognition of tumors and prompt intervention are associated with a positive outcome. Degrees of success are relative to the accessibility and invasiveness of the tumor. Maintenance of eyesight can be difficult as many horses can require enucleation to excise invasive ocular tumors. Secondary spread to regional lymph nodes may support a poor prognosis and may influence the decision to initiate treatment. Of tumors that are 7 completely excised, twenty-two percent recur without adjunctive treatment.1 Discussion Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for approximately twenty percent of all equine mucocutaneous tumors arising in places such as the periocular region, the genitalia, and nasal and oral mucocutaneous junctions.1 The most common location for squamous cell carcinoma is the periorbital region, with the eyelid most commonly affected.2 It continues to present a therapeutic challenge to practitioners; most often because horses are presented to a veterinarian far too long after initial recognition of the tumor and surgical excision is no longer possible. Most squamous cell carcinomas are locally invasive and slow to metastasize, but metastasis to local lymph nodes is not uncommon.3 If metastasis to lymph nodes is diagnosed, the affected node should be surgically removed if possible and the prognosis downgraded considerably. Several treatment modalities have been successful in eliminating or managing squamous cell carcinoma, with surgical excision and intratumoral chemotherapy yielding the best results across the literature. The most common course of treatment is surgical excision or debulking followed by a form of adjunctive therapy, such as hyperthermia, cryotherapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and photodynamic therapy. Various success rates of these treatments have been reported, however, comparing these publications can be difficult because it is difficult to control for the type and severity of the squamous cell carcinoma affecting the horses in the study. In reality, treatment success might not be the most critical factor in choosing a course of therapy. Owners generally prefer therapies that are administered once, at the time of surgery, resulting in fewer visits to the veterinarian. Recently, hyperthermia and cryotherapy have been used less 8 frequently as they have only shown moderate success clinically.1,4 Various types of chemotherapy have been used extensively in the field. Cisplatin can be administered in two different approaches, intralesional injection of a viscous fluid and implantation of biodegradable beads allowing the drug to be released over time. In one study, beads after surgery had a 60% success rate.1 The cost is approximately twenty dollars per bead and most often five beads are needed. 5-fluorouracil is available as a topical cream and as a sterile, injectable solution. The topical cream is popular is as an alternative to other chemotherapy drugs because it does not require special preparation or equipment to deliver, and is relatively inexpensive. Treatment recommendations vary in duration and frequency from daily application for two weeks to twice monthly for eight months. A success rate of 90% was found in horses with squamous cell carcinoma of the external genitalia that received combination therapy in the form of surgical excision and 5-fluorouracil application.5 Mitomycin-C can be placed in sterile sponges and applied to the surgical field after tumor resection for one to five minutes. Reported success is 70%.6 Photodynamic therapy is a technology that has been around for decades but only recently is being used in the treatment of periocular squamous cell carcinoma in horses. Photosensitizer drugs are preferentially absorbed by proliferating tissue, which allows for selective uptake by tumor cells.7 The drug is injected locally at the site of the tumor and the cells are then destroyed when light is delivered to a highly specific area. Pilot research has shown promising success however more data are necessary to compare this new treatment with other established modalities.8 In our patient we chose radiotherapy with Strontium-90 because it is hopefully a one-time treatment, with good reported success, that can be performed immediately after surgery. This treatment is difficult to use in the field because of the initial cost of the Stontium-90 probe and 9 the special training, certification, and handling required to use the probe. However, in a hospital setting, Strontium-90 is an easy treatment. Because the radiation can only penetrate 2mm strontium-90 should only be used for superficial lesions. One study reported an 83% success rate strontium-90 radiation when combined with surgical excision.1 Complications include loss of hair pigment, permanent epilation, palpebral fibrosis, and cataract and corneal ulceration; none of which were seen in our patient. 10 References 1. Taylor, S. and G. Haldorson, A review of equine mucocutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Equine Veterinary Education. 2013 25: 374-378. Print. 2. Kaps, Simone, et al. Primary invasive ocular squamous cell carcinoma in a horse. Veterinary Ophthalmology. 2005 8: 193–197. 3. Limawararut, Vanessa, et al. Periocular squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2006 35: 174-185. Print. 4. King, Tracey, et al. Therapeutic management of ocular squamous cell carcinoma in the horse. Equine Veterinary Journal. 1991 23: 449-452. Print. 5. Fortier, L.A. and MacHarg, M.A. Topical use of 5-fluorouracil for treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the external genitalia of horses: 11 cases (1988–1992). J. Am. Vet. Med. Ass. 1994. 205: 1183-1185. Print. 6. Rayner, S.G., and N. Van Zyl. The use of mitomycin C as an adjunctive treatment for equine ocular squamous cell carcinoma. Australian Veterinary Journal. 2006. 84: 43-46. Print. 7. Sherman, Wesley, et al. Photodynamic therapeutics:basic principles and clinical application. Therapeutic Focus. 1999 4: 507-517. Print. 8. Guiliano, Elizabeth, et al. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of periocular squamous cell carcinoma in horses: a pilot study. Veterinary Ophthalmology. 2008 11: 27-34. Print. 11