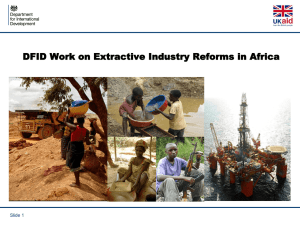

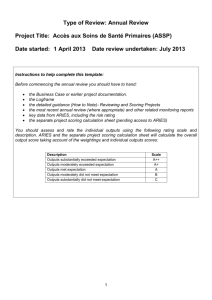

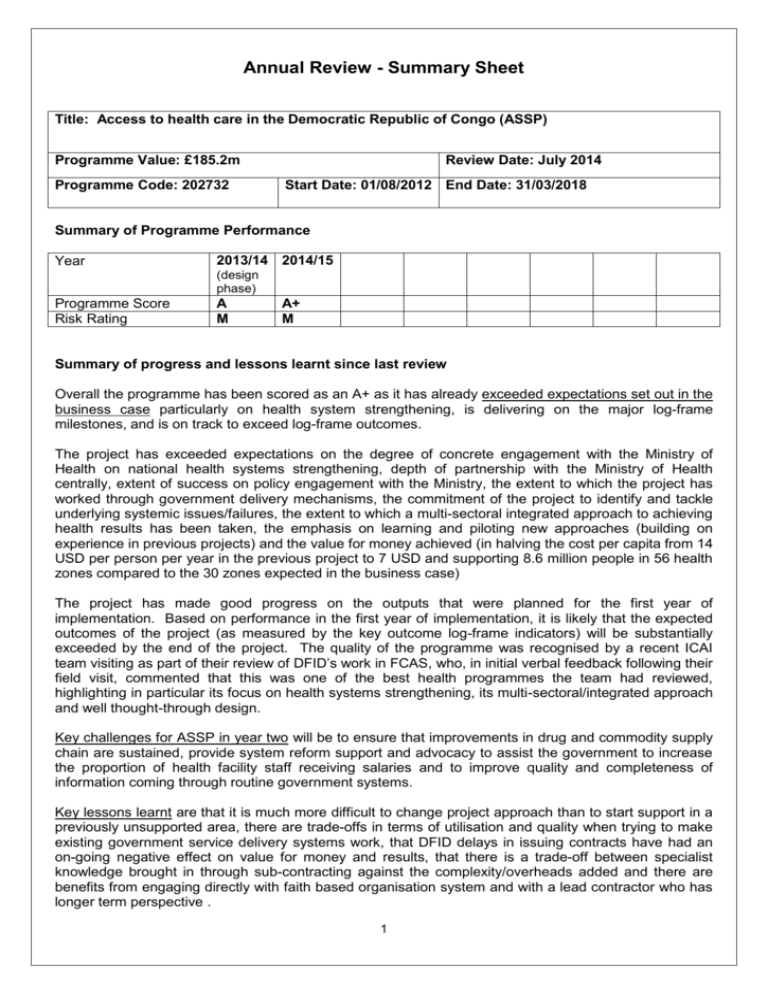

c: detailed output scoring - Department for International Development

advertisement