Are Kitchens Still the Hearth of the Home?

advertisement

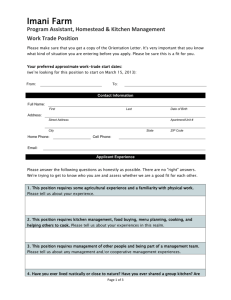

June 2012 GLS Symposium Jennifer Chutter—SFU Is the kitchen still the hearth of the home? I hate cheesy kitsch with sayings like “home is where the heart is,” “home, sweet, home,” or “If you don’t like the fire, stay outta the kitchen.” If the slogan is crossstitched in peach and blue and mounted in a tacky bronze painted frame with a white ribbon adhered to the back in order to hang it from, I feel particularly ill. These overly romanticized notions of home have nauseated me since early adolescence. Rather than explore my possible dysfunctional notions of home and some hidden trauma attached to it during hours of therapy, I decided to become an academic instead. I started with the question “is the kitchen still the hearth of the home” because I am intrigued by the amount of money people are putting into their kitchen and how infrequently people seem to be cooking from scratch. Do you need a $3000 oven to warm up a frozen pizza? Have we somehow become a nation obsessed with shiny new appliances that we have forgot what the actual purpose of them is? Are kitchen appliances the new status symbol? Has the kitchen become the new Victorian parlour, a room to display our wealth and values? As I began my research, I came to realize there are distinct differences, between American and European values embodied in kitchen design; Canada falls somewhere in the middle. “The modern kitchen in America was shaped by the commercial circle of consumers, journalists, manufacturers, and advertisers rather than a critical architectural avant-garde” like it was in Europe.1 For the purposes of this presentation, I have decided to only discuss changes to American kitchens in the last one hundred years and how it relates to the notion of hearth. A hearth is the floor of a fireplace, and by its very nature is messy, covered in ash, soot and partially charred pieces of wood. The hearth stimulated the senses with the hiss and crackle of wood burning, the smell of bread baking and a stew simmering in a pot over an open flame. Since the need for warmth and food is continual, the kitchen, the room that grew around the hearth, was the warmest room in the house and also the best lit. As a result the idea of hearth is often synonymous with household and family and is viewed as the center of home life because it was the one place the entire family would gather. Eating, socializing and sleeping often took place in this room. In many pre-twentieth century homes, especially in rural areas, the kitchen was the largest and central room in the house. I argue that no other room in the house has been so strongly influenced by changes in technology, science, moral values, consumerism, class, family values and feminism in the last one hundred years. All of these shifting ideals are reflected in Ellen Lupton and J. Abbott Miller, The Bathroom, the Kitchen and the Aesthetics of Waster: A Process of Elimination (Dalton, MA: Studley Press, 1992), 48. 1 1 June 2012 GLS Symposium Jennifer Chutter—SFU Is the kitchen still the hearth of the home? the design and function of the kitchen space and in turn has challenged our view of the kitchen embodying the ideas of hearth. I question the movement towards clean lines, stainless steel appliances and the use of expensive materials as to whether it is slowly eroding the idea of hearth because cost of the kitchen renovations does not seem to correlate with an increased cooking or socializing at home. In At Home: An Anthropology of Domestic Space, Irene Cierraad argues “there has never been a period in Western urban history where people spent so little time at home.”2 In order to simplify my approach, I looked at the average middle class kitchen and the changes that ensued within that space. The shift towards the modern day kitchen, as we know it, began before the twentieth century and this shift was more prominent in the United States than in Europe. Catherine Beecher, an American, who published The American Woman’s Home, On Principles of Domestic Science in 1869, sought to make kitchens more efficient by reducing the number of steps between cooking, preparing and washing. She argued that women were not sufficiently prepared for their “life work” in the way men were and just as efficiency models had improved industry, so could increased efficiency in the kitchen improve the “work life” of women. Subtly, the Puritanical ideas of order and cleanliness were applied to kitchen design because Beecher felt that true happiness could only be achieved by devoting oneself, as a wife and a mother, to the improvement of family life, just as God had intended. Her work was one of the first texts to apply scientific language to domestic space. “Her efficiency studies determined that the traditional freestanding tables and dressers should be replaced by compact work surfaces with shelves and drawers beneath them.”3 This idea of making kitchens more efficient was precipitated by two changes. Firstly, in the United States there was a shortage of domestic help. Women were responsible for care of their entire household and secondly, with the rise of industrialization; scientific principles were applied to all aspects of society. At the beginning of the 20th Century, changes to the kitchen began as a result of infrastructure changes as urban environments became more developed. The kitchen became connected to the wider world as it was the first room to be wired for electricity and the advent of running water and a sewer system changed how the room was constructed because of the need for it to be attached to urban infrastructure. As a result, by the 1920s most urban homes had either a gas or an electric stove rather wood or coal burning stove and the fireplace was moved to the living room. Irene Cieraad. At Home: An Anthropology of Domestic Space (NY: Syracuse University Press, 1999), 11. 3 Akiko Busch, The Geography of the Home: Writings on Where We Live (NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999), 42. 2 2 June 2012 GLS Symposium Jennifer Chutter—SFU Is the kitchen still the hearth of the home? Christine Frederick, also an American, further developed Catherine Beecher’s ideas, fifty years later, by applying scientific management principles, or what was known as Taylorism, to kitchen design in her work Household Engineering: Scientific Management in the Home published in 1919. She argued that kitchens should more closely resemble scientific laboratories. Similar cooking ‘tools’ should be clustered together and the heights of counters should be standardized in order to reinforce the idea of orderliness and cleanliness. However, domestic anthropologist, Judy Attfield points out that Frederick’s flaw in her argument is that the kitchen is designed for one worker to carry out many tasks whereas a factory functions on the division of labour and therefore Taylorism could not be adequately applied to the functioning of the kitchen.4 Similar to a factory where a single task is located in a specific area, activities such as eating, socializing and sleeping were moved to their own separate rooms as the physical shape of the kitchen became smaller and closed off from the rest of the house in an effort to minimize the number of steps taken to complete a task. Beecher’s and Frederick’s arguments dramatically shifted the appearance of kitchens. Rather than mismatched pieces of furniture holding various cooking items around the room, with a possible separate pantry and washing area, cupboards started to come in standard sizes and fit around the appliances. While domestic scientists purported the kitchen was becoming more functional with uniform counter heights and standard sized cupboards, the actual functionalism of the kitchen was beginning to be eroded. The height of the surface for baking needs to be much lower than it is for chopping. In order to prepare baked goods, the surface needs to be lower so you can see in the bowl to check the consistency and to knead and roll out dough. Ranges were designed to be at the same height as the countertops with the oven below, which meant that women were bending over lower in order to take things in and out of the oven, a design feature many women complained about. While several models were developed with the oven raised and the cooking surface beside, they did not catch on because the desire for clean lines and uniformity in the kitchen was seen as being more important than the actual ease in which cooking tasks could be undertaken. Margarete Schutte-Lihotsky, a German architect, further refined Beecher and Frederick’s ideas of efficiency and scientific management. In 1926, she developed the galley kitchen, which came to be known as the Frankfurt kitchen. Rather than free-standing cupboards and shelves, cabinets became fixtures permanently adhered to the walls and built around appliances. This marked a significant shift in kitchen design because the space went from being highly individual full of furniture to suit the needs of the family to permanent standardized height and depth of Judy Attfield, Wild Things: The Material Culture of Everyday Life (Oxford: Berg, 2000), 251. 4 3 June 2012 GLS Symposium Jennifer Chutter—SFU Is the kitchen still the hearth of the home? cupboards and work surface in the name of efficiency. It also reinforced the idea that kitchens should be kept orderly and clean. The narrow galley kitchen further strengthened the idea that the only activity to take place in the kitchen is cooking, as there was no room for a table to be placed in the room. One of the main criticisms of her design was that the kitchen was so small only one person could cook there. Schutte-Lihotsky believed that an efficient kitchen would release women to work outside the home because the tasks required to care for the family could be done in a shorter amount of time. This view contrasts sharply with the American idea that an efficient kitchen would allow women with more time to be better wives and mothers. By shrinking the square footage of the kitchen in order to maximize efficiency between work areas, by closing it off from the rest of the house and by limiting the room to a single function, the kitchen began to resemble the aspects of a laboratory rather than a hearth. The laboratory aspect became further supported as new forms of technology entered the home designed to make cooking more precise combined with recipes becoming standardized with specific weights and measures. Cooking became an exact science with pounds, cups, and teaspoons quantifying ingredients rather than relying on recipes passed down generations with dashes of spices, a handful of raisins and two teacups of flour. The appearance of the room also became standardized with white tiles, white walls and white cupboards dominated because the dirt could easily be seen and removed further reinforcing the laboratory aesthetic for American kitchens. Steven Gdula argues in his work, The Warmest Room in the House, that in the early twentieth century, “individuality was something to be sanitized and, along with the germs, food contaminants, and unhealthy lifestyles, removed from the kitchen.”5 However, the scientific approach to kitchen design began to be challenged in the 1950s. Kitchens took on a renewed significance in the post-WWII period and throughout the cold war as a way of strengthening the ideals of home and nation. Firstly, there was a glorification of domestic duties and the importance of women carrying out their work at home was emphasized because with men returning from the war women needed to leave the workforce. Beecher’s idea of a more efficient kitchen as a way to grant women more time to be better wives and mothers was reclaimed as a goal for a modern society. The goal was not to release a homemaker from the drudgery of kitchen chores, but to ensure that she was better able to fulfill her domestic duties. The rise in the number of household appliances did not release her from the amount of time she was spending on housework, but merely increased the expectations placed on her to keep the house clean. Secondly, in an attempt to showcase all the positives of industrial development to a nation shattered by the Steven Gdula, The Warmest Room in the House: How the Kitchen became the heart of the twentieth-century American Home (NY: Bloomsbury, 2008), 7. 5 4 June 2012 GLS Symposium Jennifer Chutter—SFU Is the kitchen still the hearth of the home? destructiveness of war, the kitchen and the related gadgetry became important. The practical purpose of the advancements in technology as a result of the war was emphasized. Rather than factories laying in waste after the need for munitions declined they were converted to mass-producing stoves, fridges, dishwashers and washing machines. The push for consumer goods had a two-fold purpose, one to boost the economy and the second to define Americans as progressive and entering into the age of modernity. Americans reinforced these ideas by displaying model kitchens publicly at home in shopping malls and abroad at Fairs and Expos in order to encourage consumer spending on kitchens. Advertising images relied on nostalgic ideas of hearth; many images had a woman in her much larger kitchen with children underfoot joyous cooking on her new electric range. Modern American society was moving away from the tiny Frankfurt kitchen and white was slowly abandoned as a dominant colour scheme as appliances began to be manufactured in a variety of colours in an attempt to remove the sterility of the laboratory kitchen aesthetic. As Cristina Carbone argues in Cold War Kitchen, coloured appliances “were meant to be understood as a celebration of the freedom of choice of American homeowners and housewives (even if fictitious) and of their ability to individualize their kitchen and separate it from the countless other suburban kitchens of their neighbours.”6 The ideal of Americans celebrating their individuality and freedom dominated cold war politics. Developments in kitchen design were seen as a way to promote the significance of American technological innovation to combat the technological feats of the Russians entering space first. In 1959, Nixon met with Khruschev in the kitchen at the model home at “America’s national exhibition in Moscow.”7 They debated American and Soviet rockets and appliances with equal seriousness. Nixon stressed the importance of having an abundance of choices in technology is what was making the United States strong whereas Khruschev thought the collective energy of the nation towards the specific goal of space exploration was of greater national importance. However, in both countries the idea of home and especially the kitchen came to be closely allied with ideas of nationalism and national identity. New homes built in the post-war period, in both Europe and the United States, needed to embody the ideas of home and a progressive modern nation. Shute-Lihotsky’s standard efficient kitchen resting on mass produced pre-fabricated materials became the fastest way to achieve the goal of building adequate housing quickly in post-war Europe. The United States, also adopted the pre-fab efficient kitchen with the construction of suburbs. The increased standardization in materials and appliances allowed for homes to be produced quickly as cabinet sizes Christina Carbone, “staging the Kitchen Debate: How Sputnik got normalized in the United States” in Cold War Kitchen, ed. Ruth Oldenziel and Karin Zachmann (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2009), 70. 7 Ibid., 60. 6 5 June 2012 GLS Symposium Jennifer Chutter—SFU Is the kitchen still the hearth of the home? and countertops became standardized. Over the last fifty years kitchens have become larger and more open to the rest of the house moving away from the tiny closed off room the kitchen once was; however, the motivations behind the design changes are varied. Some argue that the kitchen became open to the rest of the house to allow the person in the kitchen to still view the television, the new hearth of the home, while others argue it is based on a desire to be closer to family life while preparing food. Still others argue that by opening the kitchen up women are less segregated away from the rest of the house and it allows for a greater sense of equality. I think there is still the push for the idea of hearth and an attempt to create some sense of individuality in our kitchens. We put pictures on the fridge and clutter the counter with personal knick-knacks in order to mark the territory as our own. We are wiling to spend money to change the kitchen to suit our own personal preferences, whether it is the colour of the walls or the tiles, the knobs and drawer pulls or the mouldings. Yet, as Friedman and Krawitz argue, “the attachment to home appears to be more an attachment to the concept of home than to the actual home itself.”8 We are willing to spend a large sum of money renovating so the space is exactly the way we want it, but we are quick to move and start the process again in a new house. In many newer homes, the kitchens are becoming larger with spaces for eating, lounging or carrying on a variety of activities. It has moved away from the singular purpose of the mid-20th century design. However, we are still caught in this interesting dichotomy where we have a renewed sense of hearth in one sense with multiple people and multiple purposes taking place in the same room, but with central heating the room itself is not a space that generates actual physical warmth and fewer people are actually cooking from scratch which eliminates much of the sensory experience of hearth. I believe that the kitchen itself has become the showpiece of the home more than its actual hearth. We are a generation brought up watching television and consuming processed foods, yet the past ten years has seen a proliferation of cooking shows enter the airwaves. I believe that these shows would not be popular if we were not nostalgic for a sense of hearth; however, I believe that the television is the center of family life and not cooking in the kitchen. Increasingly, our kitchens also resemble the kitchens on television shows, “today in many houses the kitchen has become the grandest interior, stainless steel theatres where guests congregate to admire gleaming industrial equipment and the culinary feats of the host or hostess.”9 This creates a show atmosphere where there is a separation between chef and recipients of the Avi Friedman and David Krawitz. Peeking Through the Keyhole (Montreal: McGillQueen’s University Press, 2002), 166. 9 Akiko Busch. Geography of Home: Writings on where we live (NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999), 43. 8 6 June 2012 GLS Symposium Jennifer Chutter—SFU Is the kitchen still the hearth of the home? meal. Akiko Busch argues in her work, Geography of Home: Writings on Where We Live, that we have a reluctance to give up domestic rituals in the name of modern efficiency; however, rather than reverting to traditional cooking methods of a simple tool preparing a simple meal we are relying increasingly on smaller appliances and other kitchen tools to support our domestic desires. Busch furthers her argument by stating that we cultivate sensory experiences to counteract the “increasing engagement with the electronic realm.”10 I think the only was we can create a sense of hearth in the kitchen is by cooking from scratch and that means letting go of the laboratory aspect of kitchens. By turning the preparation of food into a science and by stressing the importance of cleanliness, we have lost the sense of play in the kitchen. Hearths, by their very nature are messy, but create a sensory experience of home and belonging. This process of perpetual generation and consumption mimics the life cycle process and one, I believe, gives our soul rest. 10 Ibid., 44. 7