Quality Pre-K Programs

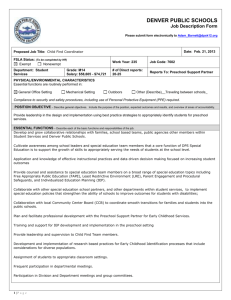

advertisement

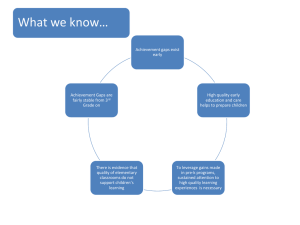

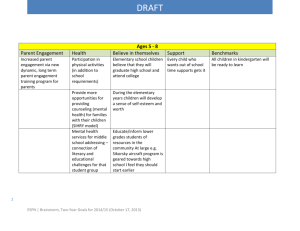

Quality Pre-Kindergarten Programs Cait Miller Policy Research Intern University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Forum Study Group XV: “Education 24/7” In the United States, 76% of children of age three and four receive education and care from someone other than a parent, with 58% attending a center-based program, defined as preschool, child care, or Head Start.1 This large number of young children enrolled in early education programs creates an opportunity to provide programs that will adequately prepare these children for schooling and careers later in life. Researchers have determined that for children, particularly from lower income backgrounds to benefit from early education, these programs must be of high quality standards.2 When looking at what goes into making a quality preschool program, it is helpful to focus on the two dimensions of process and structure. Process quality emphasizes experiences that occur in educational settings and structural quality includes the structural and teacher characteristics of a program. While what makes a quality preschool program may differ in specifics between nations or within states, these aspects all have been shown by studies to be very important in early childhood development. Section 1: Process The process typically involves the experiences that go into an early education program. Curriculum and assessment are both major parts of the process dimension. Other experiences tend to include interactions between students and teachers or students and their peers and the activities that make these interactions possible. Learning opportunities, materials provided, and health and safety routines all also factor into the process dimension. The following sections will explore various best practices for process quality and compare these to the methods used currently in NC Pre-K education. A. Curriculum Broad curriculum standards are targeted at promoting a more even level of quality across differing age groups and provision. They strive to guide and support professional staff in their practice, to facilitate communication between staff and parents, and to ensure pedagogical continuity throughout the transition from early childhood education into school. It is believed that general goals of socialization and well-being are more important for younger children, while specific cognitive aims benefit older preschool students.3 The National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) has shown through studies that a focus on skills rather than Espinosa, Linda (2002), “High-Quality Preschool: Why We Need it and What it Looks Like”, Preschool Policy Matters, NIEER, New Jersey. 2 See Footnote 1 3 Eurydice (2009), “Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe: Tackling Social and Cultural Inequalities”, Eurydice, Brussels. 1 1 activities can help to make social and emotional goals more concrete.4 Broad curriculum aims for early childhood education include: “learning to be”-confident and happy with oneself “learning to do”-experimentation, play and group interaction “learning to learn”-specific educational objectives “learning to live together”-being respectful of differences and democratic values5 Currently in North Carolina, preschool curriculum structure follows closely to suggested best practice goals. Each NC Pre-K program must have a curriculum that has been approved by the NC Child Care Commission and specific curriculum approaches include: pondering, processing, applying experiences curiosity, information-seeking, and eagerness risk-taking, problem-solving, and flexibility persistence, attentiveness, and responsibility imagination, creativity, and invention aesthetic sensibility6 B. Assessment Assessment is a measurement of process quality created by observing the experiences that occur in the classroom and rating the multiple dimensions of the program. These dimensions tend to include teacher-child interactions, type of instruction, room environment, materials, relationships with parents, and health and safety routines. The Early Childhood Environmental Rating Scale (ECERS) has been used across the nation as a measurement for process quality.7 This Scale includes: 43 items organized in seven areas of center-based care for kids ages 2.5-5 Seven focus areas include: personal care routines, space and furnishings, language reasoning, interaction, activities, program structure, parents and staff Each item has detailed descriptors and can be rated from 1-7 with 1 being inadequate and 7 being excellent. Higher rated activities correspond to greater development of advanced math abilities and social skills8 North Carolina uses the ECERS scale to assess Pre-K classrooms across the State, ensuring they are on track. Assessors report feedback in a detailed summary back to site NIEER (2004), “Class Size: What’s the Best Fit?” Policy Brief, NIEER, New Jersey. OECD (2006), Starting Strong II: Early Childhood Education and Care, OECD, Paris 6 Public Schools of North Carolina (2012), Foundations: Early Learning Standards for North Carolina Preschoolers and Strategies for Guiding Their Success. 7 See Footnote 1 8 http://ers.fpg.unc.edu/c-overview-subscales-and-items-ecers-r 4 5 2 administrators. If the score is less than a 5, an improvement plan will be developed to enhance program quality. NC Pre-K funds may be terminated if a program does not meet requirements.9 C. Family Involvement Research has shown that involving parents in early childhood education can enhance children’s achievements and adaptation.10 Parental involvement is independently associated with school performance and achievement starting from early childhood and continuing through midadolescence.11 Parental needs and policy goals should be combined in order to provide reliability and accountability in early childhood education. Currently North Carolina implements policies that encourage family involvement. NC Pre-K contractors must provide a comprehensive plan for family engagement to implement strategies that help to form partnerships with families and generate shared decision-making. Some examples of these opportunities include home visits, parent/teacher conferences, classroom visits for families, parent education, family involvement in decision making, and other opportunities to engage families outside of the regular service day.12 A log of these interactions must be kept on file at the NC Pre-K site.13 D. Professional Development Studies show that professional development has a positive relationship with teaching abilities and student achievement gains. While a number of federal initiatives are driving states to develop effective professional development systems, there is a lack of consistent professional development policies.14 North Carolina currently supports professional development programs to enhance the preschool education workforce. These policies include: Licensed Administrators, teachers, and teacher assistants in nonpublic and public schools must participate in professional development consistent with the State Board of Education policy. Administrators, teachers, and teacher assistants in nonpublic school settings who are working towards Pre-K qualifications must participate in a minimum of six semester hours per year.15 Section II: Structure The structure entails the structural and teacher characteristics of a preschool program. These characteristics include adult-child ratio, staff qualifications and compensation, program 9 ECERS-R (2011), A Guide to the North Carolina Pre-Kindergarten Environment Rating Scale Assessment Process OECD (2012), Starting Strong III: A Quality Toolbox for Early Childhood Education and Care 11 Glass, G. (2004), “More than Teacher Directed or Child Initiated: Preschool Curriculum Type, Parent Involvement, and Children’s Outcomes in the Child-Parent Centres”, Education Policy Analysis Archives, Vol. 12, No. 72, pp. 1-38. 12 Division of Child Development and Early Education (2012), NC Pre-K Program Requirements and Guidance 13 See Footnote 12 14 Demma, Rachel (2010), “Building an Early Childhood Professional Development System”, NGA Center for Best Practices. 15 See Footnote 12 10 3 duration, and age of children within the program. Structural aspects are thought to contribute to quality in more indirect ways than process aspects. These features of early education programs are often regulated through state licensing requirements. A. Group Size and Staff-child Ratios Research has found that smaller groups lead to more positive and simulating interactions between teachers and children.16 Research has shown that staff-child ratios are generally the most consistent predictor of high-quality learning environments as they increase the number of valuable interactions between teachers and children.17 With a smaller number of children to each adult, safety standards improve as staff members have fewer children to look after.18 It has been reported that younger and disadvantaged children tend to benefit more from smaller group size than older or advantaged children.19 It has been suggested that there should be two adults available for each group of 18 children.20 Currently, North Carolina Pre-K staff-child ratios are consistent with best-practice recommendations. NC Pre-K policies state that the classroom will not exceed a maximum staffto-child ratio of 1 to 9 with a maximum class size of 18 children.21 B. Staff Qualifications Research has shown that better educated preschool teachers with specialized training in early education tend to be more effective in providing stimulating staff-child interactions. These qualifications tend to leave teachers with larger vocabularies and increased problem-solving abilities that are more likely to improve children’s cognitive outcomes. A study by the Effective Provision of Pre-School Education in England found that higher proportions of staff with lowlevel qualifications were associated with poorer child outcomes on social relationships with peers and children’s cooperation and higher levels of anti-social behavior.22 On the other hand, teachers with specialized training and higher education levels were associated with positive child-adult interactions, including praising, comforting, questioning, and responding to children.23 The following shows where North Carolina stands relative to required staff qualifications. North Carolina offers some flexibility for teachers who are not fully certified to earn licensure while teaching. 16 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2000). Characteristics and quality of child care for toddlers and preschoolers. Applied Developmental Science, 4 (3), 116-135. Peisner-Feinber, E.S., et al. (1999). 17 Pianta, R. C., W.S. Barnett, M. Burchinal and K. R. Thornburg (2009), “The Effects of Preschool Education: What We Know, How Public Policy Is or Is Not Aligned With the Evidence Base, and What We Need to Know”, Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 49-88. 18 See Footnote 11 19 See Footnote 8 20 Schools.nyc.gov 21 See Footnote 12 22 See Footnote 8, p. 36 23 Elliot, A. (2006), “Early Childhood Education: Pathways to Quality and Equity for all Children”, Australian Education Review, 50, 2006. 4 All lead teachers must hold or be working toward a NC Birth through Kindergarten (B-K) or Preschool Add-on Standard Professional II licensure. Teachers working toward the required licensure must have a minimum of a BA/BS degree and an additional one of four approved licenses. All teachers assistants must hold a GED and hold or be working toward a minimum of an Associate Degree in early childhood education, child development, or child development associate. 24 C. Teacher Compensation Studies have shown that setting minimum wages for early education staff can increase the motivation of current staff and attract highly motivated and qualified professionals to the sector and this can indirectly improve child development and outcomes.25 The National Institute for Early Education Research suggests that Pre-K teacher salaries should be raised to those of comparably qualified K-12 teachers.26 Higher wages attract stronger professional staffs more willing to make long-term commitments resulting in lower staff turnover rates. These lower turnover rates in generally result in stronger relationships between children and staff, calmer child behavior, and improved language development.27 Another study found that fully qualified early education teachers who were paid salaries equivalent to primary education colleagues resulted in student performance that was two or more times larger in literacy and math.28 In North Carolina, teachers in public Pre-K programs receive salaries based on the NC Public School Salary Schedule for Certified Staff and receive benefits from the NC State Health Plan and NC State Retirement System. Licensed Pre-K teachers in private schools are eligible to receive a compensation package.29 D. Program Duration Research shows that longer program duration times tend to be associated with more benefits. Increased duration has been shown to promote greater vocabularies, word analysis, math achievement, and better memory.30 Also, longer duration programs tend to have more visible long-term impacts and reduced fade out effects. North Carolina’s Pre-K programs have the following requirements to try to ensure effective program duration: NC Pre-K sites must provide a Pre-K program for a minimum of 6.5 hours per day for 180 instructional days per calendar year. 24 See Footnote 12 National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) (2003), “Low Wages=Low Quality: Solving the Real Preschool Teacher Crisis”, Policy Brief, NIEER, New Jersey. 26 See Footnote 1 27 Canadian Council on Learning (2006), “Why is High-Quality Child Care Essential? The link between Quality Child Care and Early Learning”, Lessons in Learning, CCL, Ottawa. 28 See Footnote 11 29 See Footnote 12 30 See Footnote 9 25 5 Whenever possible, hours of operation should be consistent with the local school system where the program site is located.31 Conclusion Access to a quality preschool program is very important to starting out a child’s educational experience in an effective way. Structure and process quality play a major role in determining the effectiveness of early education programs. This paper compares best-practice aspects within both structural and process quality to what the state of North Carolina currently requires from NC Pre-K. Overall, it is found that North Carolina’s quality standards for NC PreK are very similar to those that are suggested as broader best practices. 31 See Footnote 12 6

![Service Coordination Toolkit Transition Planning Checklist [ DOC ]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006933472_1-c85cecf2cfb8d9a7f8ddf8ceba8acaf8-300x300.png)