(2010). Managerial Learning as Co-Reflective Practice

advertisement

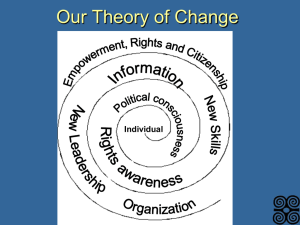

Evaluating Executive Leadership Programs: A Theory Of Change Approach Working Paper Watkins, Karen; Hybertsen Lysø, Ingunn; deMarrais, Kathleen; Abstract As executive leadership development becomes more informal and experiential, traditional evaluation models of learning transfer based on fixed objectives do not capture emerging program outcomes. What is needed is a more robust approach that looks at open objectives and what changes have occurred that impact both the individual and the organization. This paper presents an evaluation model based on Theory of Change that identifies critical incidents of new behavior and explores changes at individual, group, and organizational levels. This evaluation model relies on repositioning management learning in leadership development programs, and incorporate theories of action, workplace and organizational learning. Two case-studies of executive leadership development in the USA and Europe demonstrate the model’s usefulness. Introduction As corporations face unprecedented financial turbulence, leaders make extremely difficult choices regarding where to cut back, and even more difficult, where to invest. Many have slashed their training and development budgets (Berta, 2009), even cutting whole training departments. Others have held tight to their most strategic asset, their people, cautiously investing in HRD activities (Mattioli, 2009). Scholars in HR and management learning can help corporations make these critical choices through strong evaluation research to demonstrate the business returns of their investments in HRD. Researchers have struggled to find evaluation models that capture emerging program outcomes beyond individual learning. This paper contributes an evaluation model of executive leadership development that considers changes at different levels as well as open objectives. Existing evaluation models (Kirkpatrick, 1998; Holton & Baldwin, 2003; Belling, James & Ladkin, 2004) focus on factors enhancing or hindering transfer of individual learning back at work, and were designed to capture learning in fairly traditional training formats based on fixed objectives. Increasingly, leadership development is much more holistic, focused on challenging experiences, knowledge acquisition, skill development, and solving real business problems as in action learningbased leadership development (Blackler & Kennedy, 2004; Gosling & Mintzberg, 2006). Embedded in these complex program designs are opportunities for individuals and their managers to self-identify outcomes; and for serendipitous outcomes to emerge from the experiences, the settings selected, and the challenges faced. What is needed is a more robust approach that examines changes that impact both the individual and the organization. These executive leadership development programs in particular call for a deeper, more organizational analysis and a repositioning of management learning. Given the caliber of participants in these leadership programs, learning must be tied to the level and scope of their work—calling for more open-ended, exploratory work–embedded learning approaches that emphasize judgment, and strategic, global thinking. This calls for a more dynamic and developmental approach to evaluation, which considers the range of learning modes and levels (Marsick & Watkins, 1999), and the complexity of systems change (Patton, 2011). A relevant approach is to identify critical incidents of new behavior and to explore changes at the individual, group, and organizational level. A model with promise for capturing a complex array of outcomes is an adaptation of the Theory of Change Model of evaluation (Evaluation Forum, 2003). This paper traces how management learning in executive leadership development is being repositioned, leading us to rethink evaluation of emerging program outcomes. Second we discuss the usefulness of a theory of change approach to evaluation of executive leadership development. Finally, empirical material from two case studies of executive development programs from the USA and Europe are provided to illustrate the usefulness of this approach for HR developers. Repositioning managerial learning in executive leadership development The number of providers of leadership and management development programs and consultancies is ever-increasing, paralleling the expansion of management knowledge Sahlin-Andersson and Engwall (2002) document. Although there has been a dramatic growth in programs aiming at educating, developing and training managers, there has been increasing doubt of the relevance (Antonacopoulou, 1999), the effectiveness (Mintzberg, 2004a), and the true yield of training expenditures (Blume, Ford, Baldwin & Huang, 2010). Theorists emphasizing experience and experiential learning continuing the tradition of pragmatism associated with John Dewey have exercised considerable influence with management learning (Burgoyne & Reynolds, 1997). In general, the field of management learning seeks to reverse the privilege of theory over practice and Schön’s (1983) ideas of the professional as a reflective practitioner is one of the most prominent contributions to this field. Burgoyne and Reynolds (1997, p.8) stated that the field of management learning addresses both ideas about learning, and designs for learning; examines purposes, processes and outcomes of education, training and development activities; and engages with the worlds of theory production as well as inquiry and practice. This study of executive leadership development concentrates on the operations level, which includes evaluating and investigating managerial learning in management programs and in the workplace. In studies of management development and education, Armstrong and Fukami (2009) advocate treating formal and informal learning approaches as complementary components in the overall process of management learning. Some studies on management development stem from related studies of the design of management programs and action oriented activities for learning (Pedler, 1997) and have emphasized the importance of managers’ experience (Mintzberg, 2004b; Blackler & Kennedy 2004). An extensive portion of literature on experiential learning elaborates on teaching methods and techniques in training, such as Reynolds and Vince’s (2007) edition concerning management education. The work of Marsick and Watkins (1990, 1999) and Watkins and Marsick (1993, 2008) focuses on exploring the range of learning modes – from formal to informal to incidental that help build work-related learning capacity – and subsequently how to diagnose and create a continuous learning culture to make learning part of the DNA of the organization. Much learning is claimed to be incidental as it is taken for granted, tacit or unconscious, but can be probed and intentionally explored through a passing insight (Watson & Harris, 1999; Marsick, Watkins, Callahan, and Volpe, 2009; Hill, 2003). This repositioning leads us to rethink evaluation approaches to capture emerging program outcomes associated with more experiential, reflective learning approaches. Rethinking evaluation of emerging program outcomes Empirical studies on program outcomes have measured the success of a management program based on evidence of transfer of the managers’ learning back to the organization (Easterby-Smith, 1986). It is generally acknowledged that individual managers’ participation in management programs seldom leads to organizational development or change (Campbell, 1971; Burke & Day, 1986; Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Tannenbaum & Yukl, 1992; Holton & Baldwin, 2003). In fact, Holton and Baldwin (2003 p.4) stated that “the most commonly cited estimate is that 10% of learning transfers into job performance, and reports from the field suggest that a substantial part of organizations’ investment in HRD is wasted due to poor transfer.” Comprehensive frameworks of transfer interventions have been developed to identify key factors for overcoming this so-called “transfer problem” (Holton & Baldwin, 2003; Belling, et al., 2004). In managerial learning, transfer of knowledge and skills back to the workplace is complex, particularly when acknowledging transfer as a process that is also influenced by several factors in the recipient organization. This part of the literature assumes the relationship between training and learning is strong and program outcomes are seen as rather fixed. However, Antonacopoulou’s (2001) empirical case-study of training from the perspective of the managers’ learning as liberation of knowledge through self-reflecting claimed that the relationship between training and learning can be weak and paradoxical. When it comes to literature on emerging program outcomes, a more recent line of empirical studies of management development and education provide valuable insight into program outcomes from the perspective of the individual manager (Hay, 2006; Sturdy, Brocklehurst, Winstanley & Littlejohns, 2006; Carroll & Levy, 2008; Lysø, 2010). These studies give resonance to experienced managers’ individual change through participating in executive leadership development programs. However, these studies concentrate on the individual level of learning in terms of identity and self-confidence, and do not address the impact on the organization. A perspective of the learning organization can help us rethink evaluation of program outcomes that focus on executive leadership development. Recent meta-reviews of research exploring transfer (Burke & Hutchins, 2007; Choi & Ruona, 2008; Blume, Ford, Baldwin & Huang, 2010) and experience-based learning in leadership development (McCall, 1998; 2004; Day, 2001; DeRue & Wellman, 2009; Campbell & Smith, 2010) have reinforced the importance of a focus on organizational and workplace learning. Learning is assumed to decline if not supported by more organizational learning approaches including learning across organizational levels, availability of feedback from a network of peers and supervisors, and transparent processes of selection and development for high potential leaders. Supervisor support, goal relevance, linkage to organizational goals, and the organizational learning culture [growth and advancement opportunities, support for creativity, risk taking and innovation driven culture], and the Watkins and Marsick (1993) dimensions of a learning organization all point to the role of the organization in ensuring impact from leadership development. According to Marsick and Watkins (1999), what remains consistent across conceptualizations for a healthy organization are: (1) openness across boundaries, including an emphasis on environmental scanning, collaboration, and competitor benchmarking; (2) resilience or the adaptability of people and systems to respond to change; (3) knowledge / expertise creation and sharing; and (4) a culture, systems and structures that capture learning and reward innovation. We argue that evaluation processes must mirror this level of complexity and focus on organizational capacity building more than focusing on fixed objectives. When participants work on workplace problems in action learning programs, they not only learn by doing, but they also come face-to-face with the messy, ambiguous reality that often exists outside the classroom (O’Neil, J. and Marsick, V. 2007). This is especially true when evaluating executive leadership development programs where, given the roles of the individuals involved and the work-based activities employed in the learning process, the organization is inevitably impacted. This leads us to rethink evaluation of emerging program outcomes, focusing on change at different levels. Model of evaluation using a theory of change perspective A Theory of Change model (The Evaluation Forum, 2003) begins by asking those responsible for leadership development programs to identify the theory of change that underlies their leadership development program. Program providers identify relevant activities and show how they are linked to intended outcomes of the program. Of particular interest for programs based on action learning that operate at individual, team, and organizational levels is that they specify outcomes at four levels in Table One. Table 1 Four levels of change (The Evaluation Forum, p.6) Level Changes Short-term Individual Level changes in knowledge and skill in the program Intermediate Individual Level Organizational Level System Level changes in participant behavior demonstrated at some period after the program changes in the organization that result, in part, from expanded roles of participants changes that result in new policies, procedures, etc. that result from having better trained leaders in the organization From this tiered analysis, designers of executive learning programs can make more visible the critical outcomes of investments in leadership development. One tool to capture emerging changes at each level is the critical incident technique. The Critical Incident Technique (CIT), a method for collecting data, has been widely used in many research settings since its development by Flanagan (1954). Typically, CIT questions begin with the stem: “Think about a time when…” From these data, evaluators identify the extent to which program activities do in fact lead to intended outcomes, and potential areas where causal linkages may be fragile or broken. This provides an opportunity to capture emerging program outcomes. Two empirical case-studies illustrate this approach to evaluating executive development. Two case studies of executive leadership development Longitudinal research on executive leadership development provides opportunities to understand and conceptualize the nature of managerial learning in such programs, as well as to explore emerging program outcomes using interpretive methodology (Geertz, 1973). The empirical material used in this paper is drawn from two empirical case studies of executive leadership development situated in the USA and Europe. The European program was an off-site “leadership of change” program taking place in a network of small- and medium sized companies located in an international and export oriented region of Norway. At the time of this study, this program had served a network of different industry companies with executive leadership development for 15 years to develop their leaders to be more adaptive to change and globalization. The researcher’s role was to evaluate the program design as well as to explore emerging outcomes from the perspective of the participants. The U.S. program was a senior executive development program that targeted individuals who directly reported to senior vice- presidents in a ten billion a year global healthcare company. The program incorporated action learning teams and spanned four months. Interviews were conducted with participants, their supervisors, peers, and subordinates. The data from the U.S.-based organization that follows illustrates the use of the theory of change framework as a heuristic to analyze program outcomes. Demonstrating the evaluation model: The Global Healthcare Company In this study, individual executives who participated in an action-learning focused executive development program responded to critical incident prompts in four major skill areas of the program [globalization, innovation, strategic thinking, and communication]. In addition, peers, subordinates, and supervisors were asked to give similar critical incidents from their observations of the participant in order to establish triangulation of the new behaviors. In all, a total of fifty-six individuals were contacted. Respondents for phase one of this study were 14 of 15 participants, 9 of 10 supervisors, 9 of 15 peers, and 8 of 15 subordinates [N = 41]. Following this phase of the study, data were presented to human resource executives on findings. This led to re-design of some aspects of the program. Finally, follow-up interviews were conducted with the participant and their supervisors [N = 23]. Questions were more global, seeking retrospective observations of the role of the development program in the individuals’ evolving leadership capacities. As seen in Table one below, findings presented to leadership focused on outcomes at multiple levels. At the individual level, we observed transfer of some skills, integration of feedback, some job changes that led to continued growth, and a sense of being tapped that created high expectations. At the organizational level, a culture of up and downstream leadership, a common language, and stronger affiliation with the organization as one that invests in its people were observed. At the programmatic level, the activities with the longest term impact were the 360 degree feedback, the cohort, action learning, and the evaluation process itself as an opportunity to reflect and integrate learning. Examples of our findings from this study were captured in smaller causal maps that pulled out the big picture perspective given in Table Two such as that given in Figure One below. One of the most powerful themes researchers heard, even to the extent that a supervisor referred to it as a best practice, was the way in which the organization consciously develops talent—with the program as a new and important component of that process to tap, refine, and hone leadership skills. Figure one below illustrates how this theme was depicted using the participants’ language of up and downstream product development. Senior leadership • Create culture of development especially through coaching and talent development reviews • Create Executive Program • Tap People • Mentor Participants Program Participants • Self-analysis with tools, experience • Create cohort network through projects, Aspire program • Reflect, continue to develop leadership through new work experiences Program Participants' Subordinates • Mentoring – modeling and sharing Aspire strategies, materials • Sponsoring proteges, teams • Reviewing and supporting work of new cohort • Making critical decisions about building their team Figure 1 Becoming More Effective Mentors and Developers of People: Creating Up and Downstream Leadership Development (Watkins & deMarrais, 2010) The figure enables us to capture the theme, examples of how it manifested itself, and aspects of the organization’s culture that reinforced the theme. The elements of a theory of change approach— moving from activity to outcome to goal – while making clear the incidental development and change assumptions – enhance the findings from evaluation research such as this. We shared our learning about this evaluation with the organization. We had a number of assumptions underlying our evaluation approach, some of which did not prove accurate. We believed that higher order skills learned would be more observable through critical incident interviews and critical incidents were a useful way to identify whether or not individuals used and integrated new skills, knowledge, and beliefs. We assumed that one way to verify behavior change and transfer of learning was to ask individuals who supervised the participant, peers, and subordinates for illustrations of the new behavior in addition to the participant. What we learned was that while some surface changes such as using new tools or a new presentation were readily observable by these peers and subordinates, the more important, subtle changes in leadership were not. These changes were generally more cognitive, such as a broadening of one’s internal vision; a change of confidence in dealing with others; a greater awareness of listening more carefully; and mentoring and developing subordinates. Like our respondents, we agreed that it is very difficult to state unequivocally that the incidents given can necessarily be traced to learning through the program. Yet, even as they questioned the correlation between changed behavior and the training program vs many other influences on the individuals, everyone acknowledged that the program had some role in the new skills. Ferreting this out in a study such as this remains elusive. Finally, we believed that the evaluation process itself was an intervention that enabled participants to reflect on and re-engage their learning, and supervisors to think more deeply about the outcomes one can reasonably expect from a development program such as this. Participants agreed. One participant commented, “You know, it’s a funny thing, having this conversation with you, I think it certainly has increased the learning I got from this.” Another noted, “I think that it requires reflection, and that’s why it’s nice to actually – the way we’re doing it with you a year later is really – I can see the tremendous value in it, because when you do reflect upon it, I can point to just a number of things that clearly were affected by my participation” (Watkins & deMarrais, 2010). Watkins and deMarrais (2010) concluded, “In the end, the benefits of this program reported by participants were embedded in the experience itself- being selected, being part of a talented cohort, engaging in the global village of the organization, and producing valued outputs for key stakeholders through both the action learning project and the many different new skills and ideas they took back to their roles. They experienced being valued by the company, often being promoted, and being listened to as someone who might be “up and coming”- aspiring. These outcomes cannot be quantified like a score on a test, but we continue to believe that they increase loyalty and commitment, thereby potentially increasing performance and decreasing turnover. For individuals at this level, this is an outcome that is well- worth the cost of the program” (p. 29). The outcomes on four levels of change are summarized in Table Two. Table 2 Case 1: Aspiring Leaders Theory of Change TOC Model Elements ASPIRING LEADERS LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITIES FOLLOW-UP ACTIVITIES GLOBAL COHORT SHORT TERM INDIVIDUAL OUTCOMES GREATER GLOBAL AWARENESS SOME TAUGHT MATERIAL TO SUBORDINATES INDIVIDUALS EXPERIENCED HIGH PERFORMING TRUSTED TEAM INTERMEDIATE OUTCOMES BEING TAPPED CREATES HIGH EXPECTATIONS HIGH SUPPORT FOR INNOVATION INITIATIVE LACK OF NEW OPPORTUNITIES DIMINISHED LEARNING IMPACT ORGANIZATIONAL OUTCOMES UP & DOWNSTREAM LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT SHARED VISION, COMMON LANGUAGE ABOUT INNOVATION SYSTEM-LEVEL OUTCOMES GOALS MEMORABLE INNOVATION MODELS INDIVIDUALS MAINTAINED CONTACTS AMONG COHORT ACTION LEARNING 360 DEGREE FEEDBACK UPDATE ON RESULTS OF PROJECTS? COACHING IF SUPERVISORS FELT SKILLS NOT IMPROVED PROACTIVE LEARNERS LEARNED NEW SKILLS TO RESPOND SUPERVISORS OBSERVED WHETHER AN INDIVIDUAL COULD ADAPT FROM FEEDBACK, MOST PROACTIVE, ADAPTIVE INDIVIDUALS PROMOTED RELATED ORGANIZATIONAL ACTIVITIES & OUTCOMES INNOVATION TALENT INITIATIVE DEVELOPMENT REVIEW PARTICIPANTS MENTORED OTHERS FOR DOWNSTREAM LEADERSHP ENABLING OF SHARED LANGUAGE BY LEADERS NEW POSITIONS, GREATER PROGRAM ENLARGED ROLES AWARENESS AND ENABLED OFFERED COLLABORATION SELECTION OF OPPORTUNITY TO ACROSS UNITS NEW LEADERSHIP DEVELOP IN STRONGER RESTRUCTURED STRATEGIC SKILLS UNITS STRONGER INNOVATION IS ALREADY STRONG INSTILLS A TOOLS ENABLED LONG TERM, TOP GLOBAL EVERYONE’S STRATEGIC STRONG SHARING OF FUTURE LEADERS BUSINESS CONCERN (NOW THINKERS APPLY CULTURE OF CLEAR, COMMON WILL HAVE UNDERSTOOD THEIR SKILLS TO LEARNING VISION SHARED MORE BROADLY MORE SYSTEMAMONG TOP EXPERIENCE ACROSS WIDE ISSUES, LEADERS FROM ASPIRE, ORGANIZATION) MORE CROSSCOMMON FUNCTIONAL LANAGUAGE AND PROBLEMS TOOLS TO CREATE MORE EFFECTIVE LEADERS, BETTER ABLE TO WORK IN A GLOBAL CONTEXT, TO FOSTER INNOVATION, WORK MORE STRATIGICALLY AND AT A HIGHER LEVEL, AND ABLE TO COMMUNICATE EFFECTIVELY Demonstrating the evaluation model: The Corporate Network This case study is based on one cohort [N=22] of the executive leadership program. The skills areas of the program were similar to the previous U.S.-based case [organizational change, strategic thinking, and communication]; with adaption to increased globalization as an overarching focus. The empirical material includes transcriptions of 20 in-depth interviews with the managers during and one year after the program was completed, and extensive participatory field notes from a six week long program seminar including action-based learning activities. While these managers were at an earlier stage of their career than those in the previous case study, we see similar findings of emerging outcomes on multiple levels for the more experienced participants. The exploratory focus of the nature of managerial learning in the program led to the construction of a conceptual model, which is depicted in Figure 2 (Lysø, 2010). The learning processes among the managers in the program were characterized as developing a shared language, figuring out one’s identity as a leader, and working cooperatively with other managers to make sense of managing. Figure 2. Managerial Learning as Processes of Co-Reflective Practice (Lysø, 2010) Learning processes in the program Genera ng managemen facts Processes of co-reflec ve prac ce Managerial iden ty work oing ’s ong ry r e g a A man ng trajecto learni Making sense of managing Figure 2. Managerial Learning as Processes of Co-Reflective Practice (Lysø, 2010) This conceptual framework is based on our repositioning of managerial learning as ongoing and open-ended, and Wenger’s (1998) concept of learning trajectory is applied to emphasize this. Following this model of learning, program outcomes need to be seen as emerging. The managers’ cooperative work of making sense of the work of managing during the program sessions, as well as in the interviews with managers one year after the program was completed, gave an opportunity to explore critical incidents on different levels from the perspective of the managers. When data were presented to the program providers regarding redesign of the program, they also gave retrospective reflections of the impact of the program for the individuals’ leadership capacity and their companies over the years. The findings are similar to the previous case focused on outcomes at multiple levels. At the individual level, the majority of managers’ experienced new managerial formulations and a stronger identity as a leader. We also observed transfer of some skills, in particular communication and organizing teams. Some managers felt more self-confident to participate in strategic thinking, to work more internationally, and to change jobs (to other companies in the region) that led to continued growth. At the organizational level, more strategic thinking, better handling of change processes, and a common language, were experienced. The program activities with the longest term impact were the 360 degree feedback, action learning in terms of a real-life project, and the co-reflective processes in the cohort and in interviews with the researcher. Examples of our findings were captured according to what new managerial formulations that were demonstrated during the program and in the interviews where the managers reflected on their experience from the program and their accomplishing of the real-life change project. Concluding remarks Evaluation using a theory of change model as an interpretive heuristic focuses us on the essential premise of development programs—that through this set of activities, individuals will change. The model makes this assumption both more transparent and more challengeable, and also explores potential benefits and emerging outcomes at organizational and system levels. With so much invested in executive development programs, and so little invested in evaluating them, a theory of change heuristic is one way to help human resource development personnel make the case for this kind of development where program outcomes are less predictable, less measurable, and potentially far more impactful. References Antonacopoulou, E.P. (1999). Why Training does not imply Learning: The individual’s Perspective. International Journal of Training and Development, 4(1), 14-33. Antonacopoulou, E. P. (2001). The paradoxical nature of the relationship between training and learning. Journal of Management Studies, 38(3), 327-350. Armstrong, S.J. and Fukami, C.V. (2009). The SAGE Handbook of Management Learning, Education and Development. Sage Baldwin, T. T., & Ford, J. K. (1988). Transfer of training: A review and directions for future research. Personnel Psychology, 41, 63–105. Belling, R., James, K. & Ladkin, D. (2004). Back to the workplace: How organizations can improve support for management learning and development. Journal of Management Development, 21(3), 234-255. Berta, D. (2009). “CHART: Budget cuts burn training plans, Nation's Restaurant News, (March 23, 2009). Retrieved September 25, 2009, from http://www.nrn.com/article.aspx?keyword=&menu_id=1540&id=364518 Blackler, F., & Kennedy, A. (2004). The design and evaluation of a leadership programme for experienced chief executives from the public sector. Management Learning, 35(2), 181-203. Blume, B., Ford, J., Baldwin, T. and Huang, J. Transfer of Training: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Management 2010 36 (4) 1065-1105. Burgoyne, J., & Reynolds, M. (1997). Management Learning: Integrating Perspectives in Theory and Practice. London: Sage. Burke, M. J., & Day, R. R. (1986). A Cumulative Study of the Effectiveness of Managerial Training. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(2), 232-245. Burke, L. A., & Hutchins, H. M. (2007). Training transfer: An integrated literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 6(3), 263-296. Campbell, J. P. (1971). Personnel Training and Development. Annual Review of Psychology, 22, 565602. Campbell, M. and Smith, R. (2010). High-Potential talent: A view from inside the leadership pipeline. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership. Carroll, B. & Levy, L. (2008). Identity Construction in Leadership Development. Paper presented at the International Conference for Studying Leadership. Auckland, New Zealand. Choi, M. and Ruona, W. (2008). An Update on the Learning Transfer System. Proceedingsof the “Lifelong education and human resource development: Focused on the future 2008,” Seoul, Korea, 3-24. Day, D. (2001). Leadership development: A review in context. Leadership Quarterly 11 [4] 581-613. DeRue, D. S. and Wellman, N. (2009). Developing leaders via experience: The role of developmental challenge, learning orientation, and feedback availability. Journal of Applied Psychology. 94 [4] 859–875. Easterby-Smith, M. (1986). Evaluation of Management Education, Training and Development. Aldershot: Gower. Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 327-358. Geertz, C. (1973). The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic books. Gosling, J. & Mintzberg, H. (2006). Management Education as if Both Matter. Management Learning, 37(4), 419-428. Hay, A. (2006). Seeing Differently: Putting MBA Learning into Practice. International Journal of Training and Development, 10(4), 291-297. Hill, L. A. (2003). Becoming a manager: how new managers master the challenges of leadership. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press. Holton, E. F. III & Baldwin, T. T. (2003). Making Transfer Happen. In Holton, E. F. III & Baldwin, T. T. (eds.) Improving Learning Transfer in Organizations. San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey Bass, Publisher. Kirkpatrick, D.L. (1994). Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels. San Francisco, CA: BerrettKoehler. Lysø, I. H. (2010). Managerial Learning as Co-Reflective Practice: Management Development Programs – don’t use it if you don’t mean it. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, NTNU, Trondheim Mattioli, D. (2009). “Companies Renew Focus on Employee Training, Betting That Strong Managers Will Help Through the Recover, “WSJ, Feb. 9, 2009. Marsick, V. and Watkins, K. (1999). Facilitating learning organizations: Making learning count. London: Gower Press. Marsick, V., & Watkins, K. (1990). Informal and incidental learning: A new challenge for human resource developers. London: Routledge. Marsick, V., Watkins, K., Callahan, M., & Volpe, M. (2009). Informal and incidental learning in the workplace. In M.C. Smith (Ed.). Handbook of research on adult development and learning. London: Routledge Press. McCall, M. W. (1998). High flyers: Developing the next generation of leaders. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. McCall, M. W. (2004). Leadership development through experience. Academy of Management Executive, 18, 127–130. Mintzberg, H. (2004a). Managers Not MBAs: A hard look at the soft practice of managing and management development. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. Mintzberg, H. (2004b). Third-Generation Management Development. T+D, 58(3), 28-38. O’Neil, J. and Marsick, V. (2007). Understanding action learning. New York: AMACOM. Patton, M.Q. (2011). Developmental Evaluation: Applying Complexity Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use. NY: The Guilford Press Pedler, M. (1997). Interpreting Action Learning. In Burgoyne, J., & Reynolds, M. (1997). Management Learning: Integrating Perspectives in Theory and Practice. London: Sage. Reynolds, M. & Vince, R. (eds.) (2007). The Handbook of Experiential Learning and Management Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Sahlin-Andersson, K. & Engwall, L. (2002). The expansion of management knowledge: Carriers, Flows, and Sources. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books. Sturdy, A., Brocklehurst, M., Winstanley, D. and Littlejohns, M. (2006) `Management as a (Self) Confidence Trick - Management Ideas, Education and Identity Work', Organization, 13(6), 84160. Tannenbaum, S. I., & Yukl, G. (1992). Training and Development in Work Organizations. Annual Review of Psychology, 43, 399-441. The Evaluation Forum (2003). Guide to evaluating leadership development programs. Seattle, WA. Retrieved September 27, 2009 from http://www.capacity.org/en/resource_corners/leadership/tools_methods/tools_methods_guide_to _evaluating_leadership_development_programs Watkins, K. And deMarrais, K. (2010). A Theory of Change Evaluation of Executive Development. Technical Report. Watkins, K., & Marsick, V. (1993). Sculpting the learning organization. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Watkins, K. and Marsick, V. (2008). Trends in workplace learning in the United States. In Jarvis, P. [Ed.].The Routledge International Handbook of Lifelong Learning, London: Routledge Press. Watson, T. J., & Harris, P. (1999). The Emergent Manager. London ; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Yukl, G. (1994). Leadership in organizations (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.