La France chrétienne dans l*histoire

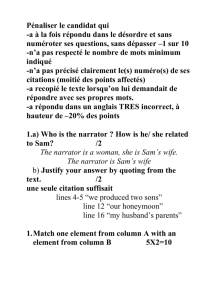

advertisement