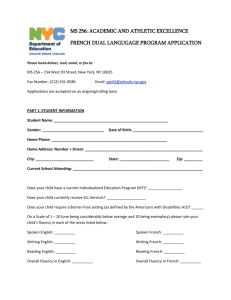

- LSA

advertisement