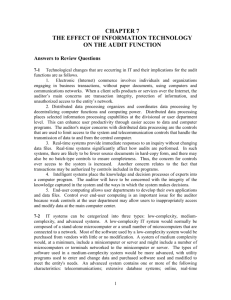

Chapter 11

advertisement