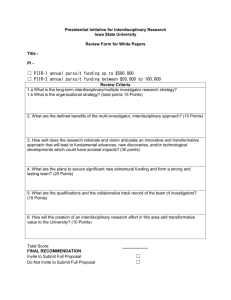

Three Dimensions of Successful Interdisciplinary Collaborations

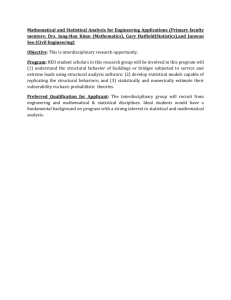

advertisement