Desperate Glory: Wilfred Owen and grim reality of WWI

advertisement

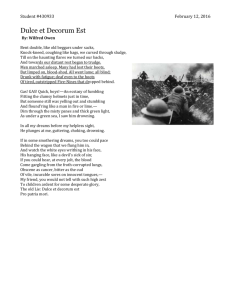

1 7 February 2015 Desperate Glory: Wilfred Owen and grim reality of WWI Countless civilizations have long heralded the bravery of those who go to battle. The Romans held soldiers in the highest regard; in “Odes”, the poet Horace writes of the glories of war: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori: How sweet and honorable it is to die for one's mors et fugacem persequitur virum country: nec parcit inbellis iuventae Death pursues the man who flees, poplitibus timidove tergo (Ode spares not the hamstrings or cowardly backs III.2.13). Of battle-shy youths. It has become so synonymous with honor and bravery that in 1913 the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in London inscribed the first line on their chapel wall (Law 44). Yet poet Wilfred Owen decried it as “The old lie...” (line 27) in his famous poem “Dulce et Decorum est”. Owen wrote the poem from his infirmary bed during WWI, providing an honest look at war through a soldier's eyes. Many idealistic young men of his time naively believed war would be an adventure (Cuthbertson 267) and, fueled by romanticized stories of patriotism and honor, came to think of the war as their noble duty (Brittain 30). However, these lies led to many losing their innocence and lives because they were unprepared for the realities of war. Those who returned were hardened by the atrocities they witnessed. “Dulce et Decorum est” presents the reader with the harsh reality of war, in stark contrast to tales of patriotism and poetic bravery. Owen's poem and his own tragic end serve as a cautionary tale from beyond the grave. When the war broke out in 1914, many writers presented an idealistic view of war through stories and poems, to be viewed as a grand adventure and a courageous sacrifice. One of these was the 2 English poet Rupert Brooke, who famously wrote, “If I should die, think only this of me / That there’s some corner of a foreign field / That is for ever [sic] England...” (“Soldier” 1-3). “The Soldier” gives us a glimpse into the mind of a young WWI soldier whose dying wish is to be remembered for his sacrifice and his duty to his homeland. Works such as this and Horace's “Odes” were used for recruitment, inspiring many young men all over Europe to join the military (Roberts 67). Wilfred Owen, then only a budding poet, became enamored with the glory of war, and recalls in “Dulce et Decorum est” those who would “...tell with such high zest … the old lie” (25-27). In 1915, he joined and was made a second lieutenant. Owen would later describe himself and his fellow soldiers as “children ardent for some desperate glory” (26), not because of their youth, but for their naivety and the abandon with which they rallied at the chance to prove themselves as proud patriots. Owen and the young men of his unit did not realize what the war had in store for them. By 1916, new innovations in weapons led to the development of grenades better suited for trench warfare; and in 1917, Germany introduced the world to the deadly and highly effective mustard gas (Fussell 10). It became clear to those on the war front that they were fighting a very different kind of battle, one they were unprepared for. “Dulce et Decorum est” recounts the dangers the young men faced: “... outstripped, Five-Nines that dropped behind / Gas! Gas! Quick, boys!” (Owen 8-9). Owen reminds the reader of their youth, yet even that left them unmatched to outrun the falling explosives and poison gas. Many were not quick enough to place on their gas masks and soon felt the lethal effects of the poisonous mustard gas. A grim picture is painted: “[on the] wagon that we flung him in, … watch the white eyes writhing in his face” (Owen 18-19), as these boys gather their broken, dying comrades, and place them in wagons to continue the march. In 1917, Owen was injured in combat and was taken to a wartime hospital, where he was diagnosed with shell shock (Owen 239). He saw himself hardened, his views changed; the reality in 3 complete disparity with the poems that inspired him to join the war effort. While confined to the hospital for his recovery, he met fellow poet Siegfried Sassoon who shared his new sentiments on the war and became encouraged to write poems about the true nature of war (Sassoon 86-90). It was here that he wrote “Dulce et Decorum est”; the graphic violence of the poem was brutally honest for its time, and worlds apart from the patriotic poems of Rupert Brooke, who had once served as Owen's inspiration. Dejected, but unflinching in his deep sense of duty, Owen returned to the front upon recovering in the summer of 1918, writing “I came out again in order to help these boys; directly, by leading them as well as an officer can; indirectly, by watching their sufferings that I may speak of them as well as a pleader can.” (Owen 351). On Armistice Day 1918, bells rang out to celebrate the end of the war, and Owen's parents received tragic news (Stallworthy 286). Wilfred had been kill on November 4th, 1918, exactly one week before Armistice; while crossing Sambre Canal with his men (Cuthbertson 293; Sassoon vi). He was only 25 years old. Bolstered by inspirational tales of courage and bringing honor to their homeland, many young men confidently joined the military, unaware of the cruelty and suffering they would soon experience. Wilfred Owen's “Dulce et Decorum est” transports the reader to the front lines of WWI, giving the audience a firsthand look as young men, weary from marching and exposed to the perils of poison gas, lose their innocence and become men only through facing tragedy and death. Owen himself joined as an idealistic youth and, after being injured, saw his views changed. He tragically lost his life upon returning to the front. Due to the efforts of his friend, and fellow soldier, Siegfried Sassoon, Owen's poetry was posthumously published (Day Lewis viii) and he became known as one of the most important writers of WWI. “Dulce et Decorum est” stands the test of time to caution those who approach battle with youthful abandon of the grim fate that awaits them. Though the literary world experienced a tremendous loss all those years ago, Sassoon put it best when he said “All that was 4 strongest in Wilfred Owen survives in his poems” (v). 5 Works Cited Brittain, Vera. “Letter from Roland to Vera. 29 Sept. 1914.” Letters From A Lost Generation: First World War Letters of Vera Brittain and Four Friends. Ed. Alan Bishop and Mark Bostridge. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1998. 30. Print Brooke, Rupert. “The Soldier.” The Collected Poems of Rupert Brooke. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1915. 115. Print Cuthbertson, Guy. Wilfred Owen. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014. Print Day Lewis, Cecil. “Acknowledgments.” The Collected Poems of Wilfred Owen. Ed. Cecil Day Lewis and Edmund Blunden. New York: New Directions Publishing Co, 1965. viii. Print Fussell, Paul. The Great War and Modern Memory. London: Oxford UP, 1975. Print Horace. Book III. 2. 13. The Complete Odes and Epodes. Trans. David West. London: Oxford UP, 2008. Project Gutenberg. Web. 4 Feb. 2015 Law, Francis. A Man at Arms: Memoirs of Two World Wars. London: Collins, 1983. Print Owen, Wilfred. “Dulce et Decorum est”. Poems. Ed. Siegfried Sassoon. New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1921. 15. Print ---. “Letter 506.” Selected Letters. Ed. John Bell and Harold Owen. London: Oxford UP, 1967. 239. Print ---. “Letter 662.” Selected Letters. Ed. John Bell and Harold Owen. London: Oxford UP, 1967. 351. Print Roberts, David. Minds at War. Philadelphia: Trans-Atlantic Publications Inc., 1999. Print Sassoon, Siegfried. “Introduction.” Poems. Ed. Siegfried Sassoon. New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1921. vvi. Print ---. Siegfried’s Journey, 1916 - 1920. New York: Viking Press, 1946. Print