World War 1 poems, readings, letters

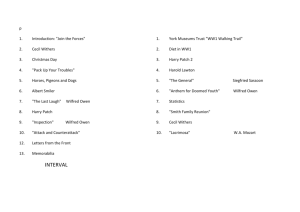

advertisement

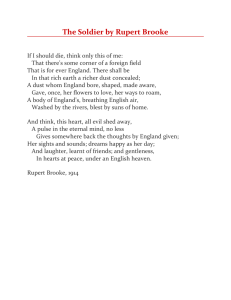

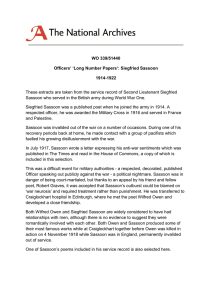

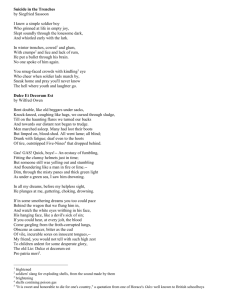

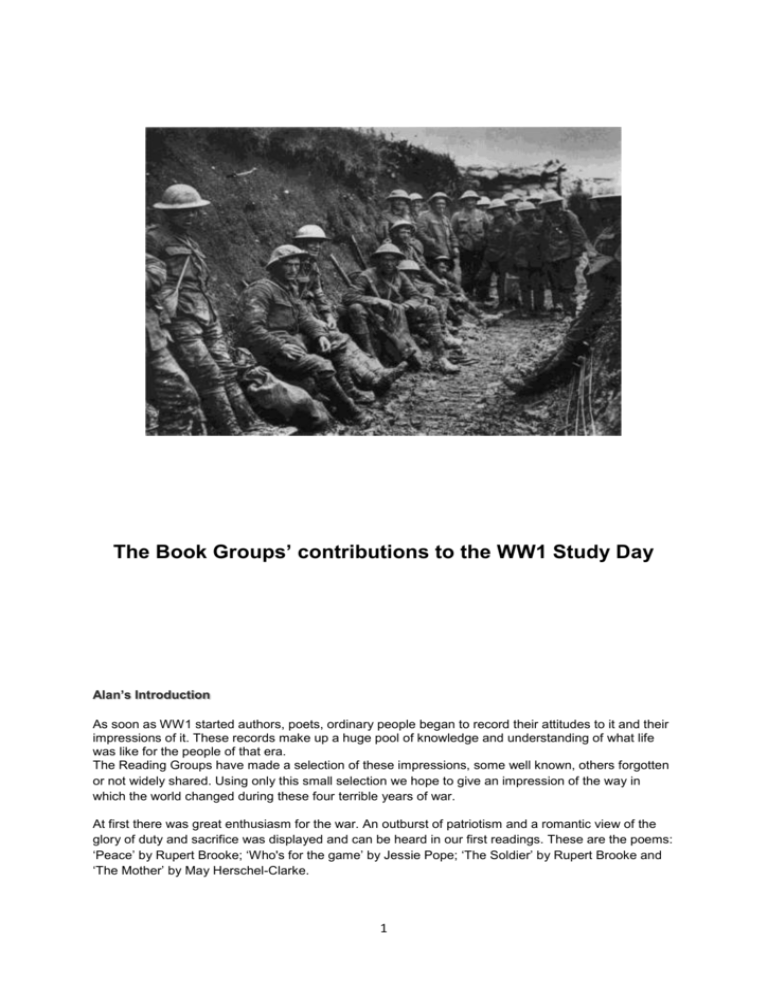

The Book Groups’ contributions to the WW1 Study Day Alan’s Introduction As soon as WW1 started authors, poets, ordinary people began to record their attitudes to it and their impressions of it. These records make up a huge pool of knowledge and understanding of what life was like for the people of that era. The Reading Groups have made a selection of these impressions, some well known, others forgotten or not widely shared. Using only this small selection we hope to give an impression of the way in which the world changed during these four terrible years of war. At first there was great enthusiasm for the war. An outburst of patriotism and a romantic view of the glory of duty and sacrifice was displayed and can be heard in our first readings. These are the poems: ‘Peace’ by Rupert Brooke; ‘Who's for the game’ by Jessie Pope; ‘The Soldier’ by Rupert Brooke and ‘The Mother’ by May Herschel-Clarke. 1 Peace, Rupert Brooke Now, God be thanked Who has matched us with His hour, And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping, With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power, To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping, Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary, Leave the sick hearts that honour could not move, And half-men, and their dirty songs and dreary, And all the little emptiness of love! Oh! we, who have known shame, we have found release there, Where there's no ill, no grief, but sleep has mending, Naught broken save this body, lost but breath; Nothing to shake the laughing heart's long peace there But only agony, and that has ending; And the worst friend and enemy is but Death. 2 Who's for the Game?, Jessie Pope Who’s for the game, the biggest that’s played, The red crashing game of a fight? Who’ll grip and tackle the job unafraid? And who thinks he’d rather sit tight? Who’ll toe the line for the signal to ‘Go!’? Who’ll give his country a hand? Who wants a turn to himself in the show? And who wants a seat in the stand? Who knows it won’t be a picnic – not muchYet eagerly shoulders a gun? Who would much rather come back with a crutch Than lie low and be out of the fun? Come along, lads – But you’ll come on all right – For there’s only one course to pursue, Your country is up to her neck in a fight, And she’s looking and calling for you. 3 The Soldier, Rupert Brooke If I should die, think only this of me: That there's some corner of a foreign field That is for ever England. There shall be In that rich earth a richer dust concealed; A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware, Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam, A body of England's, breathing English air, Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home. And think, this heart, all evil shed away, A pulse in the eternal mind, no less Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given; Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day; And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness, In hearts at peace, under an English heaven. – 4 The Mother, May Herschel-Clarke If you should die, think only this of me In that still quietness where is space for thought, Where parting, loss and bloodshed shall not be, And men may rest themselves and dream of nought: That in some place a mystic mile away One whom you loved has drained the bitter cup Till there is nought to drink; has faced the day Once more, and now, has raised the standard up. And think, my son, with eyes grown clear and dry She lives as though for ever in your sight, Loving the things you loved, with heart aglow For country, honour, truth, traditions high, —Proud that you paid their price. (And if some night Her heart should break—well, lad, you will not know.) Alan’s Link Once the romantic dreams began to fade and people realised that the war was not going to end quickly the mood changed and the need for stoicism and endurance replaced the early enthusiasm. To illustrate this we have selected: ‘Glory of Women’ by Siegfried Sassoon; ‘The Spirit’ a poem by Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy, an Anglican chaplain at the front known as Woodbine Willie. We also have two letters written by servicemen at the front to their families, contributed by one of our members, who is a relative. 5 Glory Of Women, Siegfried Sassoon You love us when we're heroes, home on leave, Or wounded in a mentionable place. You worship decorations; you believe That chivalry redeems the war's disgrace. You make us shells. You listen with delight, By tales of dirt and danger fondly thrilled. You crown our distant ardours while we fight, And mourn our laurelled memories when we're killed. You can't believe that British troops 'retire' When hell's last horror breaks them, and they run, Trampling the terrible corpses—blind with blood. O German mother dreaming by the fire, While you are knitting socks to send your son His face is trodden deeper in the mud. 6 The Spirit, 'Woodbine Willie' When there ain’t no gal to kiss you, And the postman seems to miss you, And the fags have skipped an issue, Carry on. When ye've got an empty belly, And the bulley's rotten smelly, And you're shivering like a jelly, Carry on. When the Boche has done your chum in, And the sergeant's done the rum in, And there ain't no rations comin', Carry on. When the world is red and reeking, And the shrapnel shells are shrieking, And your blood is slowly leaking, Carry on. 7 When the broken battered trenches, Are like the bloody butchers' benches, And the air is thick with stenches, Carry on. Carry on, Though your pals are pale and wan, And the hope of life is gone, Carry on. For to do more than you can, Is to be a British man, Not a rotten 'also ran,' Carry on. 8 LETTERS FROM THE FRONT This is the last letter home of 23 year old 2nd Lieutenant Tom Margerison. He had applied for transfer from a Cyclist Battalion to the Royal Flying Corps, where he became an observer in a twoseater plane, the F.E.2. A week after writing this letter, in April 1917, he and his pilot, Captain Platt, were on a reconnaissance mission over German-held territory in France, when they were shot down by a German ace, Heinrich Gontermann. Their deaths were part of the Royal Flying Corps’s ‘bloody April’ losses where the F.E.2 airplane, already obsolete by then, suffered the worst with 70 out of 100 machines being shot down. A few weeks later 57 Squadron was re-equipped with an up-to-date day-bomber. Too late for Tom. B.E.F. France April 6th 1917 My dear Mother and Father, I was so pleased to receive your letter this morning. I think Arthur’s photograph (his little brother’s) is very good indeed, and it makes one more decoration to my hut. The weather is still very changeable but in spite of this we are up on every possible occasion. There is a great deal of work to be done but up to now I have been lucky enough to come out on the right side. Today it is raining hard so that I am indoors all the time. At any rate it is warmer down below, as I can tell you that up at 14,000 feet it is enough to freeze one. Now, Mother, I don’t want to alarm you, so please do not misunderstand what I am going to tell you, or think that we are going to do anything out of the ordinary. As you know, there is now a lot of fighting in the air going on, and naturally we have our share of losses. The majority of the work is done well over the other side of the lines, so that when a machine is hit and is forced to land they 9 are at once taken prisoners by the Huns. They are shown as ‘missing’ and I am telling you this to show you that practically all the R.F.C. (Royal Flying Corps) people who are reported missing are quite safe and sound, but have been unlucky enough owing to engine trouble, to be taken prisoners. Sometimes, as actually happened in the case of two officers in this squadron, a Hun machine will drop into our lines a photograph and a note saying that certain people are taken prisoners. I also received this morning a letter from Bradford and was sorry to hear little Elsie had been bitten by a dog. I am glad you have at last heard from George (his younger brother in the merchant navy). I received his letter yesterday but owing to the Censor he was not able to tell me very much and I do not know where he is. At any rate his luck is still holding good, and he is safe. (George went down with his ship, just a year later) Owing to various circumstances I am the next observer due to go on leave as soon as this is started again. May it be soon. Well, my dear Mother and Father, I will now close With best love, Your affectionate son, Tom. A letter from the trenches, dated April 1916, from Fred Wilmot, of Hull, to his younger brother ‘Judd’. Fred was 36 and a married man with children when he was enrolled in the army. He returned from the war minus his left arm but with his Yorkshire grit intact. Years later, with a glint in his eye and the cuff of his empty jacket sleeve tucked neatly inside his pocket, he used to enjoy telling his starry-eyed little nephew that he had lost his arm in a fight - as a pirate on the high seas… April 19th 1916 Dear Brother Mine, I am just sending you a few lines to thank you very much for the parcel and at the same time let you know I am quite well and safe up to the present. I expect you will see by the papers we have had a rather rough time and a lot of casualties so I thought I would just squeeze time enough to let you have a short letter, so you would be able to let the old folks know that I was all right and had no 10 occasion to worry. Just read out what you think fit to them so they won’t be upset when they read the papers. Thank you all for your kindnesses in sending me the things you did; everything just seemed to be what I wanted and filled a gap up. We have just come out of the first line trenches wet through, nearly frozen by exposure and dead beat, so you can tell it cheered me up to get the parcel, and Ethel had sent one too. My mate and I had a right royal feast, till he went out again and came back to me in a few hours with a piece of schrapnel in his arm. Well laddie, it has rained and snowed for more than a fortnight and all the time we were making our way further to the front; the roads are awful, but how much more so are the trenches, thousands of shell holes big enough for a man to stand upright in, and then on in the night through the rain and snow to our positions, first up to the top, then over the knees in liquid mud, and still on. Shells bursting over our heads, bullets flying everywhere, enough to break anyone’s heart. As luck would have it, when our battalion went in they started a big bombardment, not half a bad start was it eh. However we got right there at last and then hour after hour on the watch, fighting with Germans only a few yards away – some places 25 yards, some 100 yards, so you can tell a little what it was like. It is an awful thing, Judd, and I am glad I am the only one who is having to get through it, and I hope it will be over before Eddie or Tom has to come over here. Here we are all together one minute and then bang bang and some are gone never to return, and others maimed and shattered for life. Our company has suffered severely, more than anyone else in the brigade. We were up against it from first going in to coming out. However I won’t dwell too long on the matter as I don’t want you to think I am in any way afraid of doing my bit. I could tell you things but it is not the time now, but if I am spared to get back home again I shall be able to speak freely. Don’t be afraid, lad, that I shall not keep my end up even to the last. I shall not be a disgrace to the old name. I think I have got a good name among my chums up to now, and hope to make a better one next time, please God. Well lad, I thank you again for your kindness in sending me those things, it was good to know someone was remembering our needs just when our spirits were at the lowest ebb and we needed encouragement most. I have just had a letter from Dad so will write a short one to him in reply, so you can keep the worst of this to yourself as I shall not tell him much. Well Goodbye for the present, dear brother mine, and the best of luck, and Good Wishes to you from your loving brother, Fred 11 Alan’s Link The horrors experienced by the troops at the front and the sense of loss felt by the families of the fallen at home eventually led to the expressions of despair and bitterness which are among the best remembered and most profound comments on the war. We have chosen ‘Survivors’ by Siegfried Sassoon; ‘Futility’ by Wilfred Owen; an extract from ‘All Quiet on The Western Front’ by German writer, Erich Maria Remarque, and perhaps the greatest response to the horror of war ‘Strange Meeting’ by Wilfred Owen. Survivors, Siegfried Sassoon No doubt they’ll soon get well; the shock and strain Have caused their stammering, disconnected talk. Of course they’re ‘longing to go out again,’— These boys with old, scared faces, learning to walk. They’ll soon forget their haunted nights; their cowed Subjection to the ghosts of friends who died,— Their dreams that drip with murder; and they’ll be proud Of glorious war that shatter’d all their pride… Men who went out to battle, grim and glad; Children, with eyes that hate you, broken and mad. 12 Futility, Wilfred Owen Move him into the sun— Gently its touch awoke him once, At home, whispering of fields unsown. Always it awoke him, even in France, Until this morning and this snow. If anything might rouse him now The kind old sun will know. Think how it wakes the seeds— Woke, once, the clays of a cold star. Are limbs so dear-achieved, are sides Full-nerved,—still warm,—too hard to stir? Was it for this the clay grew tall? —O what made fatuous sunbeams toil To break earth's sleep at all? 13 All Quiet on the Western Front, Erich Maria Remarque ‘’Take cover!’’ somebody shouts, ‘Take cover’!’ The meadows are flat, the wood is too far away and too dangerous; the only cover is the military cemetery and the grave mounds. We stumble into the darkness, and soon every man has flattened himself behind one of the mounds. Not a moment too soon. The dark turns into madness. It rocks and rages. Dark things, darker than the night itself, rush upon us in great waves, over us and onwards. The flashes of the explosions light up the cemetery. There is no way out. In the light of one of the shell-bursts I risk a glance out on to the meadows. They are like a storm-tossed sea, with the flames from the impacts spurting up like fountains. No one could possibly get across that. The wood disappears, splintered, shattered, smashed. We have to stay in the cemetery. The earth explodes in front of us. Great clumps of it come raining down on top of us. I feel a jolt. My sleeve has been ripped by some shrapnel. I clench my fist. No pain. But that is no comfort, wounds never start to hurt until afterwards. I run my hand over the arm. It is scratched but still in one piece. Then I get a knock on the head and everything blurs. But as quick as a flash comes the thought: you mustn’t faint! I sink down into the black mud but get up again immediately. A piece of shrapnel hit my helmet, but it came from so far off that it didn’t cut through the steel. I wipe the dirt out of my eyes. A hole has been blown in the ground right in front of me, I can just about make it out. Shells don’t often land in the same place twice and I want to get into that hole. Without stopping I wriggle across towards it as fast as I can, flat as an eel on the ground – there is a whistling noise again, O curl up quickly and grab for some cover, feel something to my left and press against it, it gives, I groan, and the earth is torn up again, the blast thunders in my ears, I crawl under whatever it is that gave way when I touched it, pull it over me – it is wood, cloth, cover, cover, pretty poor cover against falling shrapnel. I open my eyes; my fingers are gripped tight on a sleeve, an arm. A wounded soldier? I shout out to him – no answer – must be dead. My hand gropes on and finds more shattered wood – then I remember that we’ve taken cover in a cemetery. 14 Strange Meeting by Wilfred Owen (this poem, written in the winter of 1917, is based on Owen’s personal experience of sheltering in a shell-hole for 2 days; he dreams of meeting his German counterpart in hell; the ‘wildest beauty’ for which the young man searched was truth, but war silences truth. Poetry is seen as a redeeming force – cleansing the blood-clogged chariot wheels by revealing the realities of war.) It seemed that out of battle I escaped Down some profound dull tunnel, long since scooped Through granites which titanic wars had groined. Yet also there encumbered sleepers groaned, Too fast in thought or death to be bestirred. Then, as I probed them, one sprang up, and stared With piteous recognition in fixed eyes, Lifting distressful hands, as if to bless. And by his smile, I knew that sullen hall,— By his dead smile I knew we stood in Hell. With a thousand pains that vision's face was grained; Yet no blood reached there from the upper ground, And no guns thumped, or down the flues made moan. “Strange friend,” I said, “here is no cause to mourn.” “None,” said that other, “save the undone years, The hopelessness. Whatever hope is yours, Was my life also; I went hunting wild After the wildest beauty in the world, Which lies not calm in eyes, or braided hair, But mocks the steady running of the hour, And if it grieves, grieves richlier than here. For by my glee might many men have laughed, And of my weeping something had been left, 15 Which must die now. I mean the truth untold, The pity of war, the pity war distilled. Now men will go content with what we spoiled. Or, discontent, boil bloody, and be spilled. They will be swift with swiftness of the tigress. None will break ranks, though nations trek from progress. Courage was mine, and I had mystery; Wisdom was mine, and I had mastery: To miss the march of this retreating world Into vain citadels that are not walled. Then, when much blood had clogged their chariot-wheels, I would go up and wash them from sweet wells, Even with truths that lie too deep for taint. I would have poured my spirit without stint But not through wounds; not on the cess of war. Foreheads of men have bled where no wounds were. “I am the enemy you killed, my friend. I knew you in this dark: for so you frowned Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed. I parried; but my hands were loath and cold. Let us sleep now. . . .” 16 Alan’s Conclusion By our presence here today we are proof of the continuing horrified fascination with the First World war. Its history and literature demand a response from us nearly 100 years later. This demand was met in our final poem, written in 2008 by a 10 year old boy: ‘Never Again’ by Simon Beer. Final poem The Mother (If I should die, think only this of me: That there's some corner of a foreign field That is for ever England. Rupert Brook) If you should die, think only this of me In that still quietness where is space for thought, Where parting, loss and bloodshed shall not be, And men may rest themselves and dream of nought: That in some place a mystic mile away One whom you loved has drained the bitter cup Till there is nought to drink; has faced the day Once more, and now, has raised the standard up. And think, my son, with eyes grown clear and dry She lives as though for ever in your sight, Loving the things you loved, with heart aglow For country, honour, truth, traditions high, —Proud that you paid their price. (And if some night Her heart should break—well, lad, you will not know. 17