WORD - Northern Territory Government

advertisement

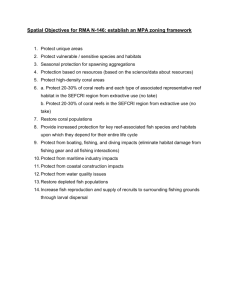

COASTAL REEF FISH – What’s the problem? The following is a summary of the scientific evidence regarding at risk coastal reef species as compiled by fisheries experts at the Department of Primary Industry and Fisheries. The Northern Territory has a reputation for recreational fishing that anglers elsewhere often envy. Our waters are home to a range of high quality sport fish and the Territory offers true wilderness fishing experiences. However, the sustainability of several popular reef species has come under threat in recent years because they are now being targeted more efficiently than before and they have biological traits, such as a schooling behaviour, slow growth rates and susceptibility to being caught before becoming mature that make them vulnerable to over fishing. Many of our reef species are also much less resilient to catch and release fishing than species such as barramundi and trevally. Ensuring the long term sustainability of key reef species in the face of advancing fish finding technology, increasing fishing effort and high rates of catch and release fishing is the most significant emerging challenge confronting Northern Territory fisheries management today. Fisheries management needs to consider the current situation but also think ahead to factor in the future. The potential for recreational fishing to expand and put even more pressure on our fishery resources is something we all need to consider. Our population is expanding and we have access to bigger and more powerful boats equipped with sophisticated fish finding technology. We are putting more pressure on our reef fish than ever before and we cannot simply rely on the productivity of our fish stocks to replenish the resource under that pressure. Not acting today to promote sustainability will raise the likelihood that much stronger management measures (such as seasonal or area closures) will be needed in the future to assist the recovery of stocks following significant depletion. The most concerning point is that with all of the new technology and knowledge available to us, we should be able to find the fish more easily and increase our catch rates if stocks are in good health. However, the fact that catch rates have declined significantly for fish species that aggregate at known sites even with technology and knowledge improvements, means that the true level of decline may be even greater and is being masked by our improving ability to still find fish within areas that are over-fished. Page 1 of 4 COASTAL REEF FISH – What’s the problem? How do we know there is a problem? Many anglers themselves have noticed there is a problem. Popular fishing spots no longer have good catches, or have become less reliable grounds for species like golden snapper. While some fishers may feel things are okay because they can still catch their possession limit from time-to-time, the reality is that fewer big (and old) fish are being caught overall at these sites. Fishers are progressively moving further afield to find spots where catches are still good. All of the observations suggest that there is a problem. In response to these concerns, fisheries scientists have studied the problem by comparing annual rates of catch-per-unit-of-effort (CPUE) to monitor fluctuations in fishing productivity and abundance over time. For the purpose of this discussion, CPUE is the number of fish caught each hour spent reef fishing. A stable CPUE across years is an indicator of sustainable catches while a declining CPUE means it is becoming harder to catch the fish and may be an indicator that stock decline may be occurring. Data from across the Territory (blue line in the graph below) show a steady decline in CPUE for reef fish (drawn from commercial and fishing tour operator logbook data). Data from the Darwin region (red line) show a significant reduction in the CPUE. A graph showing general decline in reef fish catch across the entire Northern Territory (blue line) and the significant decline in catch rates in the Darwin area (red line). (Source: Fisheries logbook data). A graph of the number of golden snapper and jewfish caught (blue bars) and the number subsequently released (orange bars) across the entire Northern Territory by resident recreational anglers. (Source: 2009/2010 recreational fishing survey data). Page 2 of 4 COASTAL REEF FISH – What’s the problem? So in summary we know from catch data that catch rates and catch numbers are declining. We also know from survey data and commercial and fishing tour operator logbook data that people are travelling further to remote fishing grounds to find fish in numbers they used to find close to home. While the evidence is clear for golden snapper and jewfish, it is important to remember that other vulnerable reef fish may also be under pressure. As further evidence, scientists also use mathematical models to analyse data and compare the current state of our resources to virgin stocks before any fishing pressure started. This involves mathematical analysis of catch trends from all sectors and determining how fishing-related mortality differs to natural mortality levels of unfished stocks based on the age and growth structures (how quickly fish grow and when they become mature spawners), reproductive capacity (how many eggs can be produced by individuals and populations) and life history traits (where and when they spawn and how many juveniles are likely to survive) of the species. As a rule of thumb, we should be maintaining the spawning potential of our stocks (when compared to virgin stocks) at about 50 or 60 per cent as a lower limit. Recent analyses show that for golden snapper our spawning potential in heavily populated areas is likely to be as low as 20 per cent of virgin stocks (well below the lower limit of 50 to 60 per cent). The graph below is an output of the golden snapper models and highlights this problem. To be fished sustainably, the ‘fried egg’ on the diagram should be below the red lines and hovering above 0.5 or 0.6 on the bottom axis (which shows the ratio of egg production potential now compared to an unfished stock). The ‘fried egg’ hovers above 0.2 on the bottom axis and the shape of the egg stretching towards the top left of the graph tells scientists that the problem is worsening as catches trend towards 2 or 2.5 times as much as they should be to stay sustainable. Ultimately, this means that to get catches back to sustainable levels we need to make at least a 30% reduction in our catch rates now so that stocks can recover. If we allow the over-catch trend to continue towards the top of the graph, the need to reduce our catches will escalate to even greater levels and closures may be the only option to achieve that recovery. Graph showing a model output for golden snapper – for the stock to recover the fried egg needs to shift to a position below the red line and to the right of 0.4 on the horizontal axis. U 2010 / Umsy refers to a comparison of current harvest rates to maximum sustainable harvest; and E2010 / E0 refers to the comparison between current egg production capacity and egg production capacity of an unfished stock. Page 3 of 4 COASTAL REEF FISH – What’s the problem? Why is any change to recreational fishing necessary? Changes to how all sectors (recreational, fishing tour operator and commercial) are managed are required to fix this problem. In the case of golden snapper, the recreational fishing community is the greatest user of golden snapper stocks by a considerable margin. Over 80% of all fish caught are taken by recreational anglers and how well the recreational sector responds will determine how solutions work. Recreational fishing survey data indicates that over 300 000 days are fished each year in the Territory by recreational anglers, representing 1.9 million hours of fishing effort. The majority of recreational fishing effort occurs within coastal areas and almost one third of it occurs in and around Darwin Harbour. A graph showing the numbers of golden snapper and jewfish caught by each sector in 2010. The recreational data refers to Northern Territory residents only and catches would go up considerably when including visiting anglers. (Source: 2009/2010 recreational fishing survey data; Fisheries logbook data). Page 4 of 4