Laura Brooks UNIV 112: Semantics and Syntax Revision February

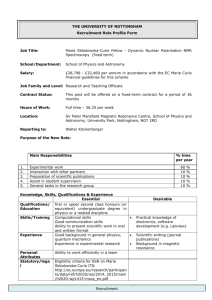

advertisement

Laura Brooks UNIV 112: Semantics and Syntax Revision February 13, 2015 Taking the good with the bad seems to be a common theme in passionate pursuits. In my experience, the bad effects serve to highlight the positive consequences. Before I was even in elementary school, I became enamored with movies and plays. Theatre became a significant part of my life early on, and I seized any opportunity I could to act. My siblings and I would create elaborate stages in my grandparents’ house to act out stories based on books we had recently read, which meant they were usually from the “Magic Tree House” series by Mary Pope Osborne. We would wrap ourselves in the sheets of colorful fabric my grandmother had not used yet and perform in the three-foot wide space where the kitchen met the den. Our impromptu shows continued until my older sister got to high school and became too old and ‘too cool’ to perform with us, but my passion never died. By the time I was 10, I had joined my elementary school’s drama club and was the lead in “The Mousetrap Mystery,” one of the two plays featured at Malibu Elementary School’s annual dinner theatre. In fifth grade, I made my musical debut as a singing penguin in “Tacky the Penguin: The Musical.” But it was not just acting, I adored watching plays, too; when the house lights dimmed, I would get swept into other worlds, none of which were ever exactly the same. This was especially intense while watching the high school plays with their intricate wooden sets and elegant costumes made for acting. In one act, the trees would be bare and eerily silhouetted by a faint light as the fog cascaded down the stage, and in the next act, the trees would suddenly sprout leaves for the artificial sun to shine through. I undoubtedly knew I wanted to be apart of it. I was lucky enough to attend Princess Anne High School, a high school known in Virginia Beach for having an exceptional performing arts department. The very first chance I got, I joined the drama club and thespian troupe, and while it was nowhere near as dramatic as science and radium’s effects on Marie’s life, it affected mine both favorably and adversely. Walking into the auditorium to audition for Arsenic and Old Lace in the fall of my freshman year forced me to confront a feeling of insecurity I developed knowing almost every one of the fifty kids auditioning was more experienced and probably more talented than I was. As I stood in line outside the classroom where auditions were occurring, my palms were sweating as I ran through the monologue over and over again in my head, trying to focus while an excited and nervous chatter filled the air. When the door opened, and it was my turn to enter, I did so with my head held high. There were two tables in the room, pushed together side by side and sitting in front of 8 pairs of eyes all focused on me as I walked onto the little black box stage. The director and company were kind and encouraging, and despite the anxiety that I felt, I was able to perform my monologue. It was that day that I received the first rejection of my high school career. It came in the form of an odd inquiry from the director, “Would you rather be a dead body or on tech crew?” I would later learn from an upperclassman that being asked that question meant I was “not terrible, but they wanted someone with more experience and an older look.” That student would later become one of my best friends while we worked together on six shows before he graduated and our friendship continues to thrive. Theatre provided me an excellent way to connect with peers in a way I never had before. Every one of us had to interact to make sure the show went smoothly, and because of that, we came to know each other on a personal level and shared things that we had never shared before. The oddest friendship that I developed through theatre was with my teacher, Mrs. Ball. After spending hours together in and out of school performing, seeing shows, and discussing all things theatre, we came to know each other and our families really well. She is the first I turn to for recommendations and occasionally advice because as I always joke, “Ball sees us more than my 2 parents and other teachers combined.” These relationships I developed apply outside of theatre as much as inside. My time management skills improved exponentially as I had to balance an advanced course workload with rehearsals, chorus shows, sleep, and family. With that, I also improved my problem solving and ability to work well under pressure, as theatre is often unpredictable. One time while I was controlling lights for the Virginia High School League OneAct district competition, a light bulb burned out before our turn and no one noticed until we had already started. The area that it lit was vital to our blocking and set placement, and it was too late to alter any of it. Despite the overwhelming urge to freak out, I maintained composure and directed one of the spotlights to focus on the darkened, which provided the necessary light and prevented the audience and judges from noticing. I have been able to utilize these skills to answer questions during interviews, class, and to balance my current coursework with community service and a social life. But at the same time, my pursuit of theatre has hurt me. I have lost countless hours of sleep due to rehearsals running late, which delayed the rest of my schedule, often including dinner, homework, and sleep back a few hours. This often meant sleeping less than six hours before waking up at 6 a.m. for school. My lack of sleep led to restlessness and trouble focusing in class, which prevented me from performing to the best of my abilities and caused unnecessary stress that permeated other areas of my life. My social life suffered as I missed spending times with friends in order to nap or make up work. My family was also adversely affected. With both my parents working and needing the cars, I often had to rely on them for rides to or from rehearsal. If rehearsal unexpectedly ran late, my dad, who had been working since 6 in the morning, may have had to wait for me for up to half an hour before I could leave or if it ended early, my parents would try and get me as soon as possible. I have also missed some important 3 events in my family and friends’ lives as a result of conflicting schedules or travelling for competitions. In the most extreme case, I missed the funeral for an extended family member because I had to travel for the state one-act competition and no one could fill in for me. I was devastated and did not get to fully enjoy the event because I wanted to be with my family and say goodbye but had to honor my commitments. The feelings of guilt and sadness I felt were amplified when we lost by a margin of less than seven points. I refused to quit, even when the negative consequences piled up because I loved theatre, and it affected my life in more positive ways than negative. In their pursuit of scientific discovery, Marie and Pierre Curie’s lives were altered in both positive and negative ways. Their pursuits led them to each other and love. It was Marie’s passion for science and desire to further her education that led her to travel to France and enroll in the Faculté des Sciences in 1891 (Redniss 25). From there, she was able to advance her knowledge and move into workspace in labs of respected inventors and scientists and ultimately, to meet Pierre. Without Marie’s passion for science leading her to France and Pierre passion leading him to be well known and respected in the scientific community, the two may have not known the love that they did. But the two were not solely lovers; they became parents, partners, and collaborators in their research. As partners in research, they were able to pursue scientific discovery together and more efficiently by helping each other and sharing their findings. In Marie’s study of radioactivity, “Pierre provided Marie with tools and a technique he had developed with his brother years earlier” (44). In doing so, it allowed Marie to begin working faster and measure data more easily. Their closeness in the lab, which is exemplified by their shared notes, research, and laboratory logs, allowed their love to deepen (57). In 1903, their cooperation culminated in them winning the Nobel Prize (73). This gained them more publicity 4 than they had previously received and the recognition allowed them to travel to new places and discuss their passions with others. However, their relentless pursuit of scientific discovery also resulted in undesirable consequences. The prolonged exposure to radiation took its toll of the couple. “Marie was too ill to travel to Stockholm to accept the award” and Pierre was growing weak (74). Marie suffered an early death at 66 due to side effects of her exposure and Pierre was remained unwell in 1906 before his death (171, 94). They did not suffer alone; their family endured the consequences as well. Marie’s residency in France meant she had to leave her family in Poland (33). When the couple started their family together, they continued to spend time in the lab and often neglected their children; then, in 1903, after years of studying radioactivity, Marie suffered a miscarriage, which was a devastating loss to the couple (74). The recognition they received was not all positive. “Marie found fame unnerving” (163). It was her position in science that made the affair between her and Paul Langevin the scandal that it was portrayed as. Paul, a former student of Pierre Curie, was in a terrible marriage and had previously taken other lovers, which his wife had tolerated (128). However, Jeanne Langevin was upset by Paul’s affair with Marie; she was so upset that “She accosted Marie and threatened to kill her if she did not leave France” (128). Her increased disdain towards Marie could have been due to her fear that Paul would leave her as he shared more in common with Marie as scientists or her dislike for foreigners as Marie originated from Poland. Madame Langevin exposed the affair just before Marie was announced as the winner of a second Nobel Prize (132). The scandal quickly escalated, much to Marie’s dismay, to the point where “Newspapers around the world reported on ‘the greatest sensation in Paris since the theft of the Mona Lisa’ ” (133). The media turned against her, and her peers in the scientific community began to doubt her with some going as far as to request her to refuse the Nobel Prize 5 (133). Marie, seeing “no connection between [her] scientific work and the facts of private life” went to Sweden to receive the award and afterwards continued to endure great disrespect (135, 146). Marie and Paul’s relationship did not last, but the rumors and glares did (148). To escape scrutiny as her health was deteriorating, Marie escaped to the countryside in 1911 until the start of World War I in 1914 (148). Despite the health problems, controversy, and judgment that Marie faced in France, she returned to aid her country and continue to further her pursuit of science (156). Marie’s determination to return and develop new equipment supports a belief that her pursuit of science was more important than the trouble it caused in her personal life. I struggle to even compare my pursuits with Marie and Pierre Curie’s. Mine is on a smaller scale than theirs as my sacrifices and the consequences were much less; however, there are some similarities. It is notable that both pursuits did affect other aspects of our lives and the way we looked at the world. Theatre opened my mind and exposed me to people I would not have met otherwise. Because we all worked together and got to know each other on a personal level during each show, it was illogical to judge a person because of their way of life. When we got down to it, there were too many similarities and more important things to worry about than categorizing each other based on stereotypes. Our discussions of our life choices were not debates or attempts to convert the other; they were conversations meant to help us clear up misconceptions and better understand our company. It made me a better, more aware person. It did so, in much the same ways that science opened the Curies’ minds to ideas of new discoveries and the idea of spiritualism. The Spiritualist movement of the nineteenth-century was centered on the idea of communicating with the deceased (52). “The movement attracted leading thinkers and artists,” and among them were Marie and Pierre Curie (53). The possibility was intriguing to these minds with Pierre believing “If the Spiritualist claims proved to be true… there was 6 ‘nothing more important from a scientific point of view’ ” (53). Because the Curies were more experimental in their scientific pursuits, they were more open to the possibility. This with their own observations and supporting measurements taken during the séances increased Pierre’s curiosity (53). While Pierre pursued the idea of Spiritualism, Marie continued her scientific pursuit with radioactivity (54). Both pursued studies that had little evidence and no guaranteed positive outcome. On the other hand, I knew that theatre would provide me a creative outlet, new opportunities, and experience I could use on résumés at the very least. It was the negative effects that I was more unprepared for. Just the phrase ‘passionate pursuit’ entails strong emotion and a chase of some sort, which already shows that it is not meant to be easy. It is our responses to the negative results that affect our view of the situations. While I had no idea of the stress that theatre would put on my academic and social life, I found ways to balance it all for the most possible benefit. The Curies were also unable to foresee the consequences of their pursuit, but they included them in their scientific research instead of giving up. From sickness to early deaths, Marie and Pierre suffered gravely as a result of their research on radioactivity, but they did so without losing their passion. When radium’s contact with his skin gave Pierre a lesion, he received it with joy, and as she was dying, “[Marie] chronicled her own deterioration as laboratory data in neat columns on graph paper” (70, 168). The negative effects did not deter the Curies or me from continuing our pursuits. Passionate pursuits are not without sacrifice, but the sacrifices can highlight the positive outcomes. There is no guarantee of success in any passionate pursuit, but the likelihood of it increases with the dedication and determination of the individual. 7