Considerations for Cost of Implementation

advertisement

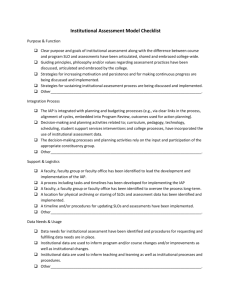

DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. Educator Evaluation Systems: Considerations for Cost of Implementation Elizabeth A. Barkowski Research Associate Value-Added Research Center Wisconsin Center for Education Research University of Wisconsin Madison barkowski@wisc.edu Association for Education Finance and Policy 38th Annual Conference New Orleans, Louisiana March 14, 2013 1 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. Educator Evaluation Systems: Considerations for Cost of Implementation Introduction and Policy Context The advent of new educator evaluation systems, spurred by state-level legislative changes as well as federal initiatives such as ESEA waivers and Race to the Top, is driving states and school districts to seek new and innovative ways to measure educator effectiveness. To date, 36 states have passed legislation and/or engaged in efforts to revamp educator evaluation systems (Education Week, 2013). These new evaluation systems generally use multiple measures of educator effectiveness, such as observations of teacher and principal practice and measures of student growth, to generate an educator’s overall evaluation rating. The ultimate goal of these initiatives is to identify educator strengths and weaknesses to help inform strategic human capital management decisions. While reforming educator evaluation systems has gained traction across the nation, the development and implementation of such systems requires time, effort, and money. Related costs could include the development of new human resource data management systems, the cost of developing and implementing metrics to evaluate teacher and principal practice, the calculation of value-added, and the implementation of other student growth measures. The direct costs of implementing educator evaluation systems may be low for some states and school districts; however, stakeholders should consider hidden, or indirect, costs comprised of the time and effort needed to implement such systems. This paper discusses the direct and indirect costs associated with the implementation of new educator evaluation systems and uses the implementation of student growth measures for traditionally non-tested teachers as a case to discuss specific costs. 2 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. Educator Evaluation System Overview Educator evaluation systems in most states and school districts typically base an educator’s evaluation rating on measures of practice and student growth. Figure 1 displays the typical breakdown of state educator evaluation system. The percentage, or weight, of the various components of an educator’s evaluation varies by state; however, states typically base 50% on measures of practice and 50% on student growth. Regardless of the weight, the cost of implementing each component would be similar. Figure 1. Basic Educator Evaluation System Student Growth (ranges from 20 – 51%) 50% 50% Educator Practice (observation) Educator Evaluation System Components and Associated Tasks Given that the various components included within new educator evaluation system are typically unfamiliar to teachers, principals, and school district central office staff, states and school districts must take time to develop or procure, train on, and implement each component of the system. This section describes the steps involved in the development and implementation of educator evaluation system components and identifies potential costs associated with each. Developing educator evaluation systems. Some states have passed legislation and appropriated funds to develop new educator evaluation systems. This process often involves the creation of a group or division within the state education agency to manage the development and 3 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. implementation process. This requires state agencies to hire or repurpose staff from other areas. States often contract with outside organizations to help lead the development process and sometimes compensate stakeholders for their work. Employees within state agencies working on educator evaluation initiatives often work to develop and implement the state system through a variety of activities, all of which would require state expenditures. These activities could include: Convene committees of stakeholders to explore options for evaluating educators. Lead committees in the development of the state educator evaluation system. Work with committees to create communication materials, guidance, and training around new systems. Present information on new systems to educators around the state. Hold workshops and trainings on how school districts will implement new systems. Develop and manage data systems needed to support the implementation of new systems. Serve as contacts for technical support around the implementation of new systems. Teacher and principal practice standards and rubrics. All educator evaluation systems include some measure of teacher and principal practice. States and school districts define professional standards for teachers and principals, which include the knowledge and skills that educators are expected to possess. States and school districts often use rubrics to measure the degree to which teachers and principals fulfill these standards. The rubrics outline specific skills and practices that relate to standards and typically include descriptions of multiple levels of performance that teachers and principals achieve in relation to those skills. 4 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. For purposes of teacher and principal evaluation, some states have adopted existing educator practice rubrics. Wisconsin and Illinois, for example, use the Framework for Teaching, developed by Charlotte Danielson, as its teacher practice rubric. Other states, such as New Jersey and Florida, provide a list of rubric options that districts can use to evaluate educator practice. Other states, such as Georgia and Tennessee, developed their own educator practice rubrics. While there is some variation in the way in which states determine how they will develop or adopt rubrics used to evaluate educator practice, each approach requires time, effort, and funding. Imagine a state that began the process of adopting educator practice standards and developing a process by which those standards will be evaluated. States and districts may engage in the following activities: Develop or adopt standards, guidelines, and rubrics to measure educator practice. Train educators and evaluators on the system, which may include in-depth training on rubrics, evaluator training and certification, annual calibration and re-certification for evaluators. Allocate time in districts to implement the system, including time to conduct observations, collect evidence of educator practice, hold pre- and post-observation conferences, submit and score evidence and observations. Instill mechanisms to track, monitor, and report evaluation results. Student growth measures. New evaluation systems typically require that a portion of an educator’s overall evaluation be based on measures of student growth. States such as Indiana, Rhode Island, New York, Tennessee, Wisconsin, and Georgia typically use two distinct types of student growth measures to evaluate teachers: (1) value-added measures of student growth and 5 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. (2) student learning objectives (SLOs). Both approaches require significant time and resources to implement. States and school districts incur specific costs when calculating value-added measures of student growth. Since most states and districts do not have the capacity to calculate such measures in-house, they often contract with nationally-recognized vendors to run the calculations. This requires states or district to pay a vendor for time and effort. Value-added also requires that states and districts collect student/teacher linkages needed to accurately identify students that were taught by a particular teacher (and thus associate those students’ growth on standardized tests with that teacher). The need for student/teacher links along with an intensive verification process could require states to upgrade state data systems. Value-added measures of student growth are limited to teachers who teach in state-tested grades and subject areas. Currently, most states administer annual assessments in grades 4-8 math and reading. In order to measure growth in non-tested grades and subjects (which encompasses approximately 70% of teachers), states and school districts may adopt the SLO process to evaluate student growth for teachers that lack standardized assessments. The SLO process requires teachers to set annual student growth targets using existing assessment data and student work as baseline data. The degree to which students meet those growth targets by the end of semester or school year is thought to be that teacher’s impact on student learning. States and districts typically use scoring rubrics to assign a score or final rating to SLOs based on the amount of growth achieved by students. These ratings are then factored into a teacher’s overall evaluation score. Principals can also develop SLOs focused on student growth at the school level. 6 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. The implementation of SLOs requires states and school districts to directly or indirectly fund the following: Development of guidelines around the SLO process, including guidelines for selecting and/or development assessments, setting growth targets, and scoring. Training sessions for educators to learn about the SLO process. Teacher and principal time to develop SLO targets and identify or develop assessments they will use to measure student growth toward meeting those targets. Teacher and principal time to approve and score SLOs. Districts may use existing staff time or hire new staff to assist with the process. Detailed Cost Example: Measures of Student Growth for Non-Tested Teachers Measuring student growth in non-tested grades and subject (NTGS) has proven a significant challenge for states and school districts. Many new educator evaluation systems require that student growth comprise a significant portion of an educator’s overall evaluation rating. The challenge is determining how to measure student growth in areas in which states do not administer standardized assessments. For example, most states administer assessments in grades 4-8 math and reading. The new PARCC and Smarter Balanced common core assessment systems will include assessments for additional grades and subject areas, but will still leave many grades and subject areas “untested.”1 Given the lack of assessments in many grades and subject areas, along with the requirement that student growth must account for a significant portion of an educator’s evaluation, states and school districts must determine ways to capture an educator’s impact on student growth. Some options may include the following: 1 For more information on the PARCC and Smarter Balanced assessment systems, please visit http://www.parcconline.org/parcc-assessment and http://www.smarterbalanced.org/smarter-balanced 7 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. 1. Procure and purchase new assessments 2. Develop new assessments 3. Use a Student Learning Objective approach This section provides a description of potential costs associated with the implementation of each option for measuring student growth in NTGS. Cost categories were identified based on knowledge of the development of new state educator effectiveness initiatives and recent proposals released by states and school districts. Estimate Assumptions Cost categories included in this section are based on potential first year costs of implementing options to measure student growth in NTGS. It is assumed that costs may decrease over time, given familiarity with various approaches to measuring student growth and the development of assessments or data system that support such measures. Option 1: Cost of Procuring New Assessments at the State Level Some states, such as Illinois2, are working to expand the grades and subjects in which students are assessed on an annual basis. Illinois, for example, plans to contract with an organization to identify assessments in NTGS, forge contracts with assessment vendors, and make these assessments available to districts through an electronic assessment platform (potentially at a reduced cost). The purpose of procuring additional assessments is to provide useful information to teachers about student levels of knowledge in a subject area and to measure student growth over the course of a school year. 2 In August of 2012, the state of Illinois released a Request for Proposal (RFP) to identify an organization to procure assessments for the state in traditionally non-tested areas. The RFP also required the proposing organization to lead a process to work with groups of educators to develop assessments in non-tested areas and create an electronic bank of assessment items. 8 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. This assessment procurement process requires knowledge and expertise, as well as time and effort, to undergo the identification of assessments and the procurement process. Finally, once a state identifies additional assessments to administer, the state or individual school districts must pay test vendors to administer these assessments. This section describes potential costs associated with the procurement of assessments at the state level and the administration of assessments at the local school district level. Table 1 identifies potential costs that states and districts might incur if they choose to procure assessments in some NTGS. State costs. The procurement of assessments at the state level would require state education agencies to identify commercially available assessments in traditionally NTGS (those other than math and reading in grades 4-8). Assume that a state agency allots staff member time to work on the assessment procurement process. An agency would potentially repurpose a portion of staff members’ time and preclude these staff members from engaging in their regular, daily responsibilities. For this reason, the agency would incur an indirect cost for implementing this process. Agencies could also contract with a vendor to provide knowledge, expertise, and guidance to assist with the procurement process. State agencies and partnering vendors may also create or procure a data system to host assessments so that districts can access, pay for, and administer new assessments. Agencies would incur the direct costs of developing and hosting such a system, as well as incur costs required for ongoing updates and maintenance. District costs. Once a state procures and makes available assessments in traditionally non-tested grades and subject areas, districts would pay testing vendors (potentially at a reduced rate) to administer these assessments. Direct costs would include the direct cost of administering 9 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. each assessment multiplying by the number of students taking each assessment. Districts would also incur indirect costs related to the time spent by teachers and principals to administer assessments. Based on the size of the district, indirect costs may also include time spent by central office staff to assist with the coordination of assessment administration and the collection and maintenance of assessment data. Finally, in order to determine levels of student growth for use within a state’s educator evaluation system, districts would contract with a vendor to calculate value-added estimates. Some assessments, such as the NWEA MAP, may have built-in structures for reporting student growth. Others may not. The direct costs associated with value-added calculations may vary by vendor. Implications. The procurement of assessments at the state level would provide districts with new options to assess students in currently NTGS and provide student growth data for teachers teaching in these areas. If a state were to undergo such a procurement process, from an economies of scale standpoint, each district in the state would not be required to spend time and effort to identify assessments and contract with vendors. Also, states could negotiate reduced test administration rates by making assessments available to all districts in the entire state. This could bring down the overall combined state and district cost of procuring and administering assessments. Regardless of the ability of states to procure assessments, it is likely that no commercial, nationally recognized, standardized assessments assessments exist in some NTGS. This means that states and districts would still be required to develop alternative measures of student growth for some teachers. This would require additional costs to implement alternative measures, such as SLOs. 10 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. Table 1. Categories of First Year Costs for Assessment Procurement Quantity Total Cost State Assessment Procurement State Agency Staff Time Guidance and Expertise # staff * # hours 1 contract - State Assessment Platform Data System Administration and Maintenance 1 system # staff * # hours - # tests * # students # hours * # teachers # hours * # principals - # students - District Cost to Administer Cost of Assessments Assessment Administration District Value-Added Calculations Option 2: Cost of Developing New Assessments at the State Level States such as Illinois and Colorado are working to convene groups of educators to develop assessments in traditionally NTGS. This process requires expert knowledge of assessment development, training for educators on the development of assessments, and compensation for experts’ time and effort. After the development of such assessments, districts can use the assessments to measure student growth in NTGS for purposes of teacher evaluation. This section describes potential cost categories associated with the development of assessments at the state level and the administration of assessments at the local school district level. Table 2 identifies potential costs that states and districts might incur if they choose to develop assessments in some NTGS. State costs. If a state decides to develop assessments in some NTGS, state education agencies might contract with national experts to lead the development process. This assumes that a state agency would contract with a vendor and pay expert facilitators to lead educators through the process of developing assessments. The state could convene expert educators and stakeholders from around the state to partake in the process, providing these experts with a 11 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. stipend to compensate for their participation. Facilitators may train expert educators on how to develop assessments, and then facilitators and experts would engage in the actual development process. Similar to the cost of procuring assessments, this estimate assumes that the state education agency would develop a data platform to host assessments so that districts can access and administer new assessments. In future years, the state might reconvene this group on an annual basis to modify assessments and develop additional assessment items. District costs. Once a state develops and makes available assessments in traditionally non-tested grades and subject areas, districts would, in theory, administer assessments free of charge. This means that districts would incur fewer direct costs associated with the administration of new assessments. This estimate assumes that teachers and principals will still allocate time to administer assessments and acquire indirect costs. In order to determine levels of student growth for use within a state’s educator evaluation system, districts could contract with a vendor to calculate value-added estimates using state-developed assessments. Implications. The development of assessments at the state level would provide districts with new options to assess students in currently NTGS and provide student growth data for teachers teaching in these areas. In contrast with the procurement of assessments at the state level, the availability of assessments without the administration cost could significantly reduce the direct costs that districts must pay when developing student growth measures for non-tested teachers. This could reduce the overall cost of implementing such measures when factoring in the cost of implementation for all districts in a state. Regardless of the ability of states and expert vendors to develop assessments, it is likely that groups of educators and experts will not develop standardized assessments in all grades and subject areas. This means that states and districts would still be required to develop alternative 12 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. measures of student growth for some teachers, such as using SLOs. This, as with the assessment procurement option, would require additional costs at the state and district level. In addition to cost, the development of assessment requires high levels of knowledge and expertise. For example, if teachers repeatedly use the same test items, it could result in a “narrowing of the curriculum.” Creating and using several parallel test forms that are equated for overall difficulty could address this; however, this would also require additional knowledge, expertise, and money on part of the state. Similarly, groups of educators creating assessments at the state level may lack knowledge of the psychometric properties of valid and reliable assessments. For this reason, the procurement of large-scale standardized assessments with wellestablished psychometric properties may provide more valid and reliable measures of student growth. Table 2. Estimated First Year Cost of Assessment Development Quantity Total Cost State Assessment Development Guidance and Expertise Facilitators Training Development 1 contract # facilitators * # days # experts * # days # experts * # days - State Assessment Platform Data System Administration and Maintenance 1 system # hours * # staff - # hours * # teachers # hours * # principals - # students - District Cost to Administer Assessment Administration District Value-Added Calculations Option 3: Cost of Implementing the Student Learning Objective Process Many states with redesigned educator evaluation systems are turning to SLOs as a solution to measure student growth in NTGS. Many states also use SLOs as an additional 13 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. measure of student growth for tested teachers. SLOs are often thought of as a no-cost or low-cost alterative to measure student growth in NTGS. While the direct costs associated with the implementation of SLOs may be lower than the procurement or development of assessments, however, hidden indirect costs exist. This section describes potential cost categories associated with the implementation of SLOs at the state and school district level. Table 3 identifies potential cost categories that states and districts might incur if they implement SLOs as measures of student growth in NTGS. State costs. In order to implement the SLO process, states must provide districts with some level of guidance and training. In this estimate, it is assumed that a state would contract with an organization or vendor with expertise in the area of SLOs. This vendor contract would include the development of SLO process guidelines and the development and delivery of training on the SLO process. Alternatively, the state could fund state agency staff to develop and train on such processes, which may or may not prove less costly. Similar to the other cost estimates, this estimate assumes that the state education agency would develop a data platform to track and monitor SLOs. This estimate assumes that the state would incur direct costs to develop or procure such a data system and fund the administration and maintenance of the system. District costs. Individual districts would assume the majority of costs included in this estimate. In order to implement and manage the SLO process, a district may hire, or repurpose, staff members to help review, approve, and score SLOs. Districts may also choose to provide stipends to educators to serve as SLO campus facilitators to assist teachers and principals with the SLO process. 14 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. Districts might also incur direct and indirect costs by sending teachers and principals to training on the SLO process. Districts might pay for substitutes to take over teacher classrooms while teachers attend training, or use existing professional development days for training. Similar, principals might attend training on SLOs, not only to learn how to develop their own SLOs but also to approve and score teacher SLOs. Indirect district costs associated with the SLO process entails teacher and principal time spent to develop, approve, and score SLOs. Teachers, for example, may spend time reviewing student baseline data and setting student growth targets. If no assessments of student growth exist, teachers might develop assessments on their own or with teams of teachers. Teachers track and monitor student progress over the course of the year, then collect evidence of final student growth at the end of the year. Principals will also spend time developing their own SLO, plus time spent reviewing and approving teacher SLOs. Principal time spent on SLOs may be reduced if campus facilitators and central office staff assist with the SLO approval and scoring processes. Implications. When solely examining direct district costs, the SLO process may appear to be the least expensive option used to measure student growth in non-tested grades and subjects; however, indirect costs that factor in teacher and principal time may be equivalent to or higher than other options. Once states complete the development of guidance and training on SLOs, they might incur few, in any, direct costs related to the SLO process. Also, a state data system is not as necessary for the implementation of SLOs as it is for the implementation of new assessments. The elimination of the state data system included in this estimate would reduce state direct costs. Regardless of costs, little standardization of SLO student growth measures exists. The level of rigor may vary across teachers, schools, and school districts. The use of teacher- 15 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. developed assessments may threaten the reliability and validity of SLO student growth outcomes. Inconsistencies in the SLO scoring process may also arise. While states and school districts could somewhat standardize the process to create quality control mechanisms, the process is still subject to issues of validity and reliability, which may or may not be present with the use of standardized assessments and value-added estimates of growth. Table 3. Estimated First Year Cost of Implementing Student Learning Objectives Quantity Total Cost District Direct Costs District Staff Salaries Campus Facilitator Stipend Teacher Training Time Principal Training Time # staff # per school * # schools # hours * # teachers # hours * # principals - District Indirect Costs Teacher Implementation Time Principal Implementation Time # hours * # teachers # hours * # principals - State Assessment Platform Data System Administration and Maintenance 1 system # hours * # staff - State Guidelines and Training 1 contract - Discussion and Policy Considerations This paper provides examples of the potential costs that states and school districts might incur when developing and implementing new educator evaluation systems. In addition to cost, stakeholders should consider the level of rigor and fidelity of implementation of evaluation system components when selecting and implementing various models. For example, statewide training for educators on evaluation system components may be costly; however, training can help the state ensure common understanding of the system and increase the likelihood that school districts will implement the system with fidelity. Within respect to selecting methods to measure student growth for teachers in traditionally NTGS, as well as other evaluation system components, it is important to consider 16 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. both direct and indirect costs associated with implementation. The use of SLOs, for example, may appear to be an easy solution to measure student growth; however, the time to implement SLOs may account for large indirect costs for school districts. Reducing the amount of time spent on the SLO process may result in compromises to consistency in rigor and the scoring of SLOs. Using nationally-recognized standardized assessments to measure student growth may be the most rigorous, valid, and reliable approach to measuring student growth; however, the direct costs of implementing this option may be high. The development of assessments at the state level may reduce assessment administration costs, yet may require much time, effort, and expertise. Also, states are not likely to acquire or develop assessments for all grades and subjects, which would require the development of alternative student growth evidence sources or SLOs. The direct costs of implementing SLOs may appear to be lower than paying for standardized assessments; however, district may incur high indirect costs to implement the SLO process. Additionally, the improper implementation of educator evaluation systems may result in unintended, negative consequences. Eventually, many states intend to use educator evaluation results to make high-stakes human capital decisions, yet inaccurate measures of educator effectiveness could result in lawsuits or other difficult matters. The use of standardized tests to measure student growth, for example, may be the most rigorous and reliable way to measure a teacher’s impact on student learning; however, the expansion of standardized tests could be costly. The use of SLOs as an alternative to standardized tests could result in gaming of the system or inaccurate measures of teacher effectiveness. If states and districts attempt to reduce costs by eliminating rigorous training on evaluation system components and reduce the time that educators spend implementing the system, then the system may not provide useful information 17 DRAFT – Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. about educator effectiveness. States and districts should consider such tradeoffs and determine how to best balance cost with rigor, reliability, validity, and fidelity of implementation. Finally, it is important for states to consider long-term costs associated with educator evaluation systems and the rigor of evaluation measures. More rigorous evaluation measures may provide more accurate and useful information about teachers. Districts may use this information to inform human capital decisions, leading to long-term cost savings. Misinformation on educator effectiveness, however, may cost districts more money in the long run. References Sawchuk, S. (2013). Teachers’ Ratings Still High Despite New Measures. Education Week. Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2013/02/06/20evaluate_ep.h32.html 18