History of U.S. Educational Philosophies: Utilitarianism and

advertisement

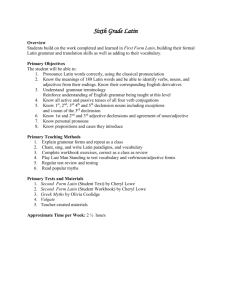

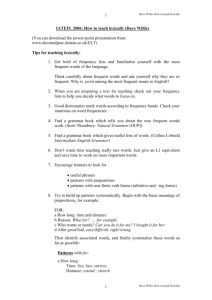

History of U.S. Educational Philosophies: Utilitarianism and Progressivism U.S. education has changed greatly since the Puritans settled in New England during the 1600s. The Puritans shaped religion, social life, and government in North America to their ideals. Their strong belief in education led them to establish Harvard and Yale as colleges and to require a system of grammar schools in the colonies. The Puritans organized their government according to the teachings that they found in the Bible and on the basis of their English experience (Wilson, 2008). There were two common beliefs among the colonists concerning education which were similar to the European education system. The first was that only a few people needed formal education. Education for the masses was uncommon in the world. European educational beliefs for the masses focused on what people needed to know for life at home, apprenticeships, and activities for daily living. There were schools for the rising mercantile classes, but formal education was reserved for a select few, such as the nobility and clergy (Marsh & Willis, 1999). The second assumption shared by the early settlers was formal education should be directed at bringing people into conformity with some prevailing ideal of what an educated person should be. This included religious training; therefore, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew were the mainstay of the curriculum (Marsh & Willis, 1999). In 1647, Massachusetts passed a law requiring every township that had 50 or more households to appoint a teacher of reading and writing, and every township with 100 households or more were required to provide a Latin grammar school. Enforcement of this law was done inconsistently (Button & Provenzo, 1983). Despite the inconsistency of enforcement, children in Massachusetts were far better educated than children in other colonies. These basic reading and writing instructions became known as dame schools. This term was coined because most of the teachers were women and conducted their lessons in their homes (Barger, 2004). Massachusetts was the forerunner of modern education including curriculum and compensatory education guidelines. The majority of children in the colonies received no formal education at all (Button & Provenzo, 1983). The most common model for formal schools was based on Latin grammar school. This was due to the church’s heavy reliance on Latin as part of their Christian teachings. The clergy needed to know the languages in which scriptures were written; therefore, the curriculum of Latin in grammar schools differed very little from the curriculum of similar schools in Europe (Marsh & Willis, 1999). The majority of the curriculum focused on reading and writing and there were some rudimentary mathematics. Students who remained beyond the first few years of school were exposed to classical Greek and Latin literature, as well as scriptures (Barger, 2004). References Barger, R. (2004). Colonial period. Retrieved from http://www.nd.edu/~rbarger/www7/ Button, H., & Provenzo, E. (1983). History of education and culture in America. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Marsh, C. J. M., & Willis, G. (1999). Curriculum: Alternative approaches, ongoing issues (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Wilson, J. B. (2008). Media and children’s aggression, fear, and altruism. Future of Children, 18(1), 87–118.