Price River - Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery

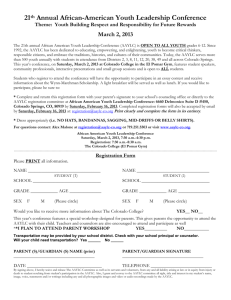

advertisement