47-Stowaways - for presenting_sat

advertisement

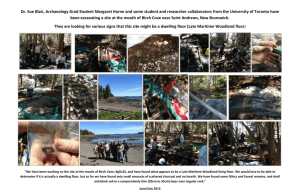

THE STOWAWAYS: DWELLING OTHERWHERE Nicholas Coetzer University of Cape Town South Africa nic.coetzer@uct.ac.za Dave Southwood Photographer Cape Town, South Africa hello@davesouthwood.com NARRATIVE 1: THE PHOTOGRAPHER One scorching Saturday I parked my car near the foreshore underpasses and picked my way across thigh-high, inhumane barriers, dodging absent- minded weekend commuters to the looming underbelly of National Road One. During the months preceding the Saturday the figures living below the highways and ambushed between the palms in the triangles of no-mans’ land which chamfers the hard civil engineering had accumulated in the corners of my eye and I’d decided meet them. I clambered up an approach to a rim of the sump slung between the highways and unexpectedly reared up above the place which I had been observing from my speeding car at street level. The acrid smelling burnt plastic, unremitting high sun, the guarantee of language misinterpreted and general trepidation at approaching a group of hardened bridge-dwellers fused sharply to give the impression of a thousand cicadas screaming. My anxious conception of this place, which I had been watching from a car for some weeks, now tightened around a man washing himself with a crooked elbow beneath a tree some 20 metres below. It takes a while for the eyes to adjust from the deep shadows cast by tons of concrete to intense white daylight. To my surprise there are at least 25 men dotted about: wedged into apexes, gambling intently at the foot of blackened plinths, collapsed under battling trees, waiting it out. Intimidated, I leave. It becomes apparent to me that on weekdays this sump is denuded of people. They must have work. The following Monday I pick my way across a more intent fusillade of sealed cars to this amphitheatre. This time my descent is easier. The bridge swings over the stream “with ease and power.” It does not just connect banks that are already there. The banks emerge as banks only as the bridge crosses the stream... The bridge gathers the earth as landscape around the stream. Martin Heidegger, Building Dwelling Thinking Heidegger’s bridge hangs large over our architectural psyche. Indeed, his often-used Building Dwelling Thinking helps bring focus to a locale in Cape Town’s Foreshore area, a place bounded by bridges and rivers of traffic. We use the word place deliberately, as Heidegger does, to signify not just the clearing of space but the articulation of space, a palpable thickening of something – into something intelligible. Heidegger notes: ‘the bridge does not first come to a locale to stand in it; rather, a locale comes into existence only by virtue of the bridge.’ The place we are interested in is an architectural accident, a leftover space as a consequence of other intentions. It is an island, the indivisible remainder of the vectors of a traffic engineering scheme and its 80km/h curving embankments and abandoned bridges. In the shadow of this design, in the spaces left over in planning, are signs of inhabitation. And of dwelling. For Heidegger, dwelling allows the fullness of what it means to be human to emerge. To dwell is not just to be at peace with the world and to have shelter and comfort; it is to bring an intensifying mindfulness to existence. Thus it is through building that the earth can be made more earthy and the sky with the season’s storms and weather it brings can be intensified – and, by extension, the sky then becomes the heavens bringing meaning to what it means to be mortal. In more esoteric terms, Heidegger refers to this heightened presence of earth, sky, the divine and mortals as ‘the fourfold.’ Buildings as strangely familiar things – here as bridges in the windswept place of the Foreshore – have the potential to bring the place and hence the fourfold into sharper focus. In Heidegger’s formula the right kind of building (as verb and noun) begets dwelling which begets thinking. But how can this admittedly powerful but ultimately hostile place, with the signs of inhabitation of here a seat and here a fireplace, be a place of dwelling? Narrative 2: Under the Bridge A strange atmosphere lingers under the bridge. Technically I am in someone’s home, but the domestic interior is ultra-public due to the roaring periphery of commuters, trucks and Kawasaki which streams incessantly and hems this stage in. At its most refined the earth under the bridges is as fine as silt, silky and inviting. At its coarse end the earth is cannon ball sized and very impractical. A misty grey light, which I have not encountered before, wraps everything gently under the highways. The thought strikes me that perhaps there is lead suspended in the air. The vast plinths seem to suck in heat, or emit coolth. The blackened, grey swathes from countless fires which spring from the gap between the earth and concrete suck in light. The scene is cast in a permanent saturnine evening. Boot prints, bottle tops, a sabre-tooth shard of metal featuring a handle made from wound-up plastic, the remains of an official travel document, the lower mandible of a cow, a half-submerged white packet flagging the spot. So this is what it feels like to be a Mars probe. I come across what must be a bed and begin to read the scrawled notes at its foot, which supports a highway. All of a sudden I realise that a ghostly armada of ships floats on a sea of graffitti. I can see inside the ships. God bless da sea Rashidi mwanza to sea neva afrika again Professor ngaribo Mzala i like ship no like pussy Sea never dry Opportunity never come twise Escape from cape Sex man chateka, from vingweta Hope to disappear “To Cry isn’t solution. You can cry till jesus will come back Bater to get ship. Stowaways! PLANNING CAPE TOWN’S FORESHORE This place, at Cape Town’s Foreshore under the bridges and embankments of the unfinished elevated highways and home to the Stowaways, is more complicated than the rudimentary evidence of dwelling seems to suggest. Beyond the elementary signs of inhabitation and the Heideggerian architectural power of the place the dwelling that exists here – dwelling as intensified human experience and contemplation – does so by resurrecting the faded lines drawn by architects and planners and their unrealised plans for the Foreshore begun some 80 years ago. The Stowaways dwell otherwhere, on the ocean, in history and in the future, their presence at the site surfaces those lines – the ghosted palimpsest places – drawn into this terrain through layer and layer of failed and mutated architectural masterplans that conclude with the elevated highways of the Foreshore. Today, it seems impossible to fathom how the city of Cape Town managed to so severely sever itself from the Atlantic Ocean that crashes its way around the coast at the Cape of Storms but it starts here with the development of Duncan Dock and this hopeful Gateway to South Africa and eventually gets undermined by this ambitious elevated ring road around the city. And so, the Foreshore bridges insist, with each plunging pylon, with each stiff line vaulting to the next, they insist on the presence of the ocean underneath the surface, on the ghostly wash of waves across the once sandy beaches of Table Bay before Duncan Dock pushed the water away. As they hit the surface with the bridge belly hovering above, the pylons plunging into the landfill of the Foreshore pulls the ocean up from below, a meniscus of expectation drawn to the surface of a dead land. With each plunge the pylons resurrect the abandoned Gateway to South Africa, a place of maritime embarkation and disembarkation, of a legitimate dwelling otherwhere. For those that are willing to look, there are signs of the ocean drawn across the embankments and bridges; a folklore of the Stowaways written onto this dead madeup land. Drawn sections of boats describe a life below decks, hiding places for Stowaways. This is the real dwelling place for the Stowaways, of dwelling otherwhere – to be at sea. As they sit literally in the shadow of design, marooned on an island dreaming of the ships that pass so close but separated by a river of traffic and an impassable palisade barrier, the Stowaways wait to steal aboard. From the safety of the river bank they plan new adventures and passages through the loopholes in the global maritime and refugee systems. It is not ironic then, that the land on which they wait is really the smooth space of the ocean called into being by the bridges under which they find shelter. For the Stowaways are quintessential Deleuzian nomads, outside of the logic of capitalism yet using its energy as a line of flight, surfing ships across global trade routes. Rather than being a dwelling place, as hinted at in the signs of inhabitation that started this paper, the place of the Stowaways under and between the bridge is a place of dwelling through thinking. The leftover places of the Foreshore bridges, through a faithful reading of Heidegger, allow dwelling not by comfort and palliative place-making compelled through Norberg-Schulz, but by allowing the Stowaways a place for ruminative thinking about the earth, the sky, the divine and mortality, about a longing for dwelling otherwhere and the authentic condition of being it allows. NARRATIVE 3: THE SHIP IS MOVEN A man has left his clothing out to dry on the grassy shoulder of the highway, at the termination of a path which seems to peter out for no reason. It’s as if, like the path’ s intention, he has evaporated in the heat. His apparel has drifted slowly to the ground. ‘Strange, innit?’ says the owner. I swivel very fast and meet a light-skinned gent with an oversized golden tooth. I know him well. ‘Adam!’ I shout. I haven’ t seen Adam in months, thought he was dead. ‘Where you been?’ I say. ‘In Russia!’ He says. ‘Mutherfuckin’ Russia’ he says, ‘Two months in a dry dock!’ Adam aka Memory Card is my anchor in this 150- man strong group of Tanzanian Stowaways from Dar es Salaam who call themselves Beach Boys and litter the beaches down to Cape Town. ‘If you come to the other wall you will see “MEMORY CARD” written there, that’s me name,’ he says supporting himself with a tattooed arm on an horizontal litany of scrawled Stowaway graffiti which appears on a vast, curved retaining wall only visible though the palisade fence which prevents the Beach Boys from entering the harbour. It’s a stand-off. His arm carries a container ship. As he leans on the wall the multiplied containers on his ship give on to the wall’s ships’ containers. The ships are drawn in section to reveal their holds, or ‘tanals’ as they are called by the Beach Boys. ‘They call me ‘MEMORY CARD’ because I always remind them what is good and what is bad... Maybe one day we gonna make it, gonna slip this life. I left my mummy in Tanzania when I was 16, stow a ship.’ This cyclical explanation comes as he limps down the length of the wall, swaying gently to and fro on a leg which has been beaten by the police, repeatedly masticating a illegal bolus in his mouth, his eyes crackling with stowaway anticipation. The next morning at 4 a.m. I received these texts: ‘Yoh I m going last night I jup ship name blu sky please keep on touch with my family fhone rochel plse tell her what is happen memory card sea power.’ And then: ‘Can feel the the ship is moven bra sound so nice alone this time but have no food only wotar still me gonna make it.’ CONCLUSION We would like to offer three observations by way of conclusion. Firstly, it is our contention that the Stowaways are exemplary subjects of Heidegger’s Building Dwelling Thinking. They fulfil all his ambitions for an authentic condition of being through dwelling as described therein and they do this by dwelling otherwhere as Deleuzian nomads. If the Stowaways are exemplary of Heidegger’s ideas about dwelling then it is because their dwelling is about thinking, it is about dwelling otherwhere: when ‘the ship is moven’. Despite the hostile conditions under and between the bridges, and without overly romanticising this rag-tag group of opportunists, we would suggest that those dwelling otherwhere do not need our sympathy but rather our admiration for being in ‘the fourfold.’ In this sense the Stowaways are architecture’s other, an unaccountable remainder outside of the palliative place-making in architectural theory that derives from so much NorbergSchulz via Heidegger and his bucolic hut in Todtnauberg. But the Stowaways are architecture’s other again; for the authentic condition of being they describe comes from occupying those spaces built by the shadow of design. This is the indivisible remainder that occurs when architects and engineers set out their totalising masterplan vision for the city or to solve a specific problem and inevitably carve the world up in a way that produces an unaccounted for shadow that others find useful. This shadow of design is inevitable. All architectural acts produce an unaccountable other outside the instrumental drive of design. Finally, architects and planners would do well to pay attention to those dwelling otherwhere because they articulate the disconnections in the desires of the city – by occupying them. We must recognise what those dwelling otherwhere say, not just about the flow of capital or social (in)justice, but about the architecture of the city. They put demands on our imagination, opening the city up to unfamiliar readings, exposing its repressed memories and anxieties. As such, this paper presents the Foreshore bridges and the Stowaways as a return of Cape Town’s repressed self. The Stowaways’ daily presence and ambition to embark insists on the return of the ocean to the city and the constitution of the abandoned maritime Gateway. They are the guilty conscience of a city, haunting it for giving up its architectural imagination for the technocratic visions of engineers and efficiency planners. Their daily presence animates the ambitions of every line drawn so starkly by the City’s architect imagining the Gateway to South Africa. Their dwelling otherwhere pulls that grand staircase of embarkation back to life.