teacher training manual for EiE

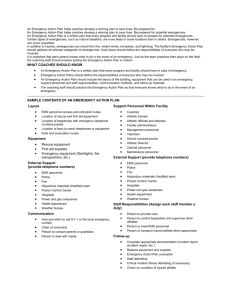

advertisement