Tabletop exercises on disaster preparedness gaining popularity w

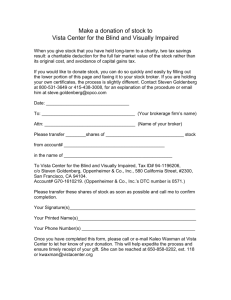

advertisement

By: Adrian Courtenay Paul Goldenberg In a growing national trend, tabletop exercises for disaster preparation are increasingly being embraced by elected officials and their stakeholders at all levels of government as powerful tools in the creation of preparedness plans for dealing with man-made or natural disasters. Tabletop exercises have been championed by DHS at the federal level since shortly after 9/11, but in the post-Hurricane Sandy era of 2013, there has been a growing realization that disaster preparedness requires total community involvement. Government officials are now being joined in the exercises by community leaders, private sector companies, faith-based organizations and other stakeholders. The term “tabletop exercises” refers to the use of simulated crises or emergency situations that are designed to measure preparedness of officials, test the resiliency of the community’s response and ensure that all stakeholders in the community — from law enforcement, first responders and public safety personnel to schools, hospitals, private sector and critical infrastructure — understand their roles and the roles of others in dealing with an emergency. The exercises also “stress-test” plans to identify gaps and areas that may require improvements. According to Paul Goldenberg, CEO of New Jersey-based Cardinal Point Strategies, and a long-time proponent, tabletop exercises are powerful tools to use in getting a shared emergency response plan in place in a state, county or municipal community, and to identify shortfalls in managerial capabilities. The plan, according to Goldenberg, is something that has to be established before an emergency takes place, so the community can be sure it is prepared when a catastrophe occurs. “Who knew before Hurricane Sandy struck in 2012 that the roller coaster at Seaside Park, New Jersey would be under 10 feet of water, or that most of Staten Island and lower Manhattan, including the subways, would be flooded? Or that a town in Quebec would see 50 of its citizens killed in a train wreck?” “Elected officials do not typically think about disasters and emergency response when they decide to run for office and start campaigning,” said Goldenberg. “But when they are sworn in and given the keys to the city, it may not dawn on them until too late that with those keys come tremendous responsibility and, in fact, their decisions during a catastrophic event may also determine who lives and dies. They soon realize that they will be responsible and accountable for the outcome — and the outcome is going to depend on how well they pulled together law enforcement, first responders, schools and hospitals, and engaged everyone in the community.” In a moving affirmation of the complexity of disaster preparedness exercises and the need for a whole community approach, Bill Akers, mayor of Seaside Heights, NJ, was recently quoted in the Newark Star Ledger in commenting on his community’s handling of Superstorm Sandy. “I could have done a lot better… I was overwhelmed… I should have delegated instead of thinking I could coordinate everything myself,” he said. According to Paul Goldenberg, there are still many elected officials, county executives, mayors, city managers and other leaders who are admittedly ill-equipped and woefully unprepared to respond to, manage and lead through a crisis or disaster that impacts their community. Large-scale crises and disasters, both natural and manmade, know no jurisdictional or geographic boundaries and require a “whole of community” approach and response. “In every case,” he said, “these incidents require leadership and capacity to meet the fundamental components of crisis and emergency management; namely, protection, prevention, response and recovery. A pro-active approach to preparedness requires forward-thinking, informed decision making and active problem solving, as well as coordination, collaboration and cooperation with the federal, state, local and private sector partners and stakeholders.” Another point that needs to be remembered, according to Goldenberg, is that DHS, FEMA and the FBI, while all very effective, are not first responder agencies. “In the first 36 hours,” he said, “you’re on your own. They’re a complement to what citizens and first responders can do.” So, the job of saving lives depends on the plan. Who is in charge? Which agency is the lead? “The key to a successful tabletop exercise,” Goldenberg continued, “is the facilitator who is responsible for eliciting questions and directing dialogue between stakeholders and enabling interaction among participants.”