Draft National Recovery Plan (2012

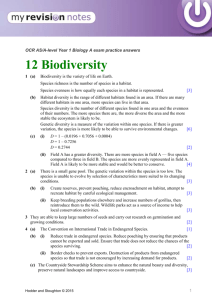

advertisement