CaseStudyCoralReefs - UCAR Center for Science Education

R.I.P. Nemo

Temperature, Acidity and the Coral Reef Bleaching

The Problem: Coral reefs play an important role on our planet. Known for their high biodiversity, coral reefs provide important resources and are active and essential components of the ocean ecosystem. A recent increase in coral reef bleaching (see below) is leading to a decline in biodiversity, a decline in available fish for food and loss of income money from tourism. There are many factors that play a role in coral reef bleaching. Some people believe it is too late for the world’s coral reefs while others believe drastic measures will help save the coral reefs. What is your opinion? Are coral reefs bleaching due to natural causes or is there something we can do about it? Read the following op-ed (opinion) article as an introduction to the issue. What is the author’s viewpoint?

A World Without Coral Reefs http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/14/opinion/a-world-without-coral-reefs.html?_r=1

(HC = hard copy included)

Your Task: Become familiar with the role of coral reefs in the earth system. Understand what coral bleaching is and what some possible causes are. Evaluate current data and decide for yourself what, if anything, should be done to save the world’s coral reefs.

Part 1 (DAY 1) – Understand what coral is, where coral reefs are located, what organisms live in coral reefs and why coral reefs are important to us. Use the links provided as well as the materials in your folder to help you find answers to the questions below as well as any other questions you can think of. How you organize your team is up to you. Consider dividing the readings into sections, each of you read one section and summarize important details for the group.

Remember, even though you are working as a team, it is your responsibility to make sure you understand everything.

You may need to search for additional sources of information.

Resources:

http://www.seaworld.org/just-for-teachers/lsa/i-030/pdf/background.pdf

Sea World Coral Reefs Background (HC)

http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/tutorial_corals/welcome.html

no hard copy, use the menu on the right side of the web page to explore different topics

Dot Earth Blog: Reefs in the Anthropocene – Zombie Ecology?

Reaction to the New York Times article used as an introduction (July 14, 2012)

http://coralreef.noaa.gov/aboutcorals/interactivereef interactive reef

http://www.coral.noaa.gov/info-resources/education-a-outreach/133.html

NOAA spawning background

Questions:

1.

What are corals?

2.

How are coral reefs formed? Where do they form? How long does it take to form?

3.

What types of organisms live in coral reefs? Give examples of several species.

4.

What do you call organisms that depend on coral reefs but live most of their lives in the open ocean? Give examples of some of these organisms.

Part 2 (DAY 2) – Become an expert on the causes and effects of coral bleaching and how scientists study coral reefs. Use the resources below to search for answers to the questions provided as well as questions you generate as a group.

Complete the Coral Reef Activity at: http://coralreef.noaa.gov/education/educators/resourcecd/activities/resources/bleaching_sa.pdf

(hardcopy included)

Resources:

http://www.skepticalscience.com/coral-bleaching.htm

skeptical review of coral reef bleaching

https://spark.ucar.edu/longcontent/corals-and-climate SPARK background information

http://www.globalissues.org/article/173/coral-reefs#Climatechangecausingglobalmasscoralbleaching background with maps

http://www.osdpd.noaa.gov/ml/ocean/cb/hot_anim.html

animation of hotspots current past 6 months

http://www.sciencedaily.com/articles/o/ocean_acidification.htm

article on ocean pH (HC)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-13605113 article about ocean acidity and deaf clown fish (HC)

http://www.whoi.edu/oceanus/viewFlash.do?fileid=55243&id=38052&aid=52990 animation showing how pH affects shell formation.

Questions:

1.

How are global hotspots changing? Are they increasing or decreasing? In all parts of the world or just some parts?

2.

What are some causes of bleaching? What other factors may stress corals?

3.

What is causing ocean pH to decrease?

4.

What earth spheres are affected by this issue? Give examples of how changes in one sphere affect other spheres.

Part 3 (DAY 3) – Data Analysis

1.

Use the data in the CoralBleachingData excel file located on the In Class Resources page at http://msdavisapes.wikispaces.com/In+class+resources to graph the severity of coral bleaching events at different sea temperatures. Is there a connection between temperature and the severity of bleaching? Is bleaching more severe during past El Nino events?

2.

Use the data in the CoralBleachingData excel file to map bleached reefs on the Caribbean map provided. Make sure your map has a key that shows the severity of the bleaching at each reef. Don’t forget to make a note of the year of bleaching.

3.

Use the fertilizer and tourism and disease data (in the same excel file) to see if you can make connections between the amount of agriculture, the amount of tourism and the severity of bleaching and or presence of diseases. Record any conclusions you made.

4.

Compare your map to the maps at: http://www.wri.org/charts-maps/publication/4919 . Can you make any more connections?

5.

Research any other possible connections you may have ideas about (ie. The number of snorkelers/divers visiting a reef or amount of fishing occurring in an area) to make further conclusions.

Part 4 (DAY 4) – Recommendations

Now that you have some evidence about what is causing coral reef bleaching, what are you going to do about it?

Time to save Nemo. Make a list of recommendations for reducing the amount of coral reef bleaching occurring in the Caribbean. Use the information and data you have collected to create convincing options that the rest of us (and the world) can buy into.

You will share your results in a brief presentation to the class. Create a Prezi or PowerPoint using the following guide:

Presentation length (8-10 minutes) o 2 minutes – background o 2 minutes – what you learned from your data analysis o 4 minutes – your recommendations and why they would work o 2 minutes for questions

Each member of your group must participate in the presentation

Be clear so others can get a good overview of your case study

Write 2-3 clicker questions to be used both before and after your presentation to gauge the feelings and opinions of your audience. This should provide you a measure of how your presentation informed you audience and changed their perceptions. These could be multiple choice, short answer, or likert scale.

Op-Ed Contributor

A World Without Coral Reefs

By ROGER BRADBURY

Published: July 13, 2012

IT’S past time to tell the truth about the state of the world’s coral reefs, the nurseries of tropical coastal fish stocks. They have become zombie ecosystems, neither dead nor truly alive in any functional sense, and on a trajectory to collapse within a human generation. There will be remnants here and there, but the global coral reef ecosystem — with its storehouse of biodiversity and fisheries supporting millions of the world’s poor — will cease to be.

Overfishing, ocean acidification and pollution are pushing coral reefs into oblivion. Each of those forces alone is fully capable of causing the global collapse of coral reefs; together, they assure it. The scientific evidence for this is compelling and unequivocal, but there seems to be a collective reluctance to accept the logical conclusion

— that there is no hope of saving the global coral reef ecosystem.

What we hear instead is an airbrushed view of the crisis — a view endorsed by coral reef scientists, amplified by environmentalists and accepted by governments. Coral reefs, like rain forests, are a symbol of biodiversity.

And, like rain forests, they are portrayed as existentially threatened — but salvageable. The message is: “There is yet hope.”

Indeed, this view is echoed in the “consensus statement” of the just-concluded International Coral Reef

Symposium

, which called “on all governments to ensure the future of coral reefs.” It was signed by more than

2,000 scientists, officials and conservationists.

This is less a conspiracy than a sort of institutional inertia. Governments don’t want to be blamed for disasters on their watch, conservationists apparently value hope over truth, and scientists often don’t see the reefs for the corals.

But by persisting in the false belief that coral reefs have a future, we grossly misallocate the funds needed to cope with the fallout from their collapse. Money isn’t spent to study what to do after the reefs are gone — on what sort of ecosystems will replace coral reefs and what opportunities there will be to nudge these into providing people with food and other useful ecosystem products and services. Nor is money spent to preserve some of the genetic resources of coral reefs by transferring them into systems that are not coral reefs. And money isn’t spent to make the economic structural adjustment that communities and industries that depend on coral reefs urgently need. We have focused too much on the state of the reefs rather than the rate of the processes killing them.

Overfishing, ocean acidification and pollution have two features in common. First, they are accelerating. They are growing broadly in line with global economic growth, so they can double in size every couple of decades.

Second, they have extreme inertia — there is no real prospect of changing their trajectories in less than 20 to 50 years. In short, these forces are unstoppable and irreversible. And it is these two features — acceleration and inertia — that have blindsided us.

Overfishing can bring down reefs because fish are one of the key functional groups that hold reefs together.

Detailed forensic studies of the global fish catch by Daniel Pauly’s lab at the University of British Columbia confirm that global fishing pressure is still accelerating even as the global fish catch is declining. Overfishing is already damaging reefs worldwide, and it is set to double and double again over the next few decades.

Ocean acidification can also bring down reefs because it affects the corals themselves. Corals can make their calcareous skeletons only within a special range of temperature and acidity of the surrounding seawater. But the oceans are acidifying as they absorb increasing amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Research led by Ove Hoegh-Guldberg of the University of Queensland shows that corals will be pushed outside their temperature-acidity envelope in the next 20 to 30 years, absent effective international action on emissions.

We have less of a handle on pollution. We do know that nutrients, particularly nitrogenous ones, are increasing not only in coastal waters but also in the open ocean. This change is accelerating. And we know that coral reefs just can’t survive in nutrient-rich waters. These conditions only encourage the microbes and jellyfish that will replace coral reefs in coastal waters. We can say, though, with somewhat less certainty than for overfishing or ocean acidification that unstoppable pollution will force reefs beyond their survival envelope by midcentury.

This is not a story that gives me any pleasure to tell. But it needs to be told urgently and widely because it will be a disaster for the hundreds of millions of people in poor, tropical countries like Indonesia and the Philippines who depend on coral reefs for food. It will also threaten the tourism industry of rich countries with coral reefs, like the United States, Australia and Japan. Countries like Mexico and Thailand will have both their food security and tourism industries badly damaged. And, almost an afterthought, it will be a tragedy for global conservation as hot spots of biodiversity are destroyed.

What we will be left with is an algal-dominated hard ocean bottom, as the remains of the limestone reefs slowly break up, with lots of microbial life soaking up the sun’s energy by photosynthesis, few fish but lots of jellyfish grazing on the microbes. It will be slimy and look a lot like the ecosystems of the Precambrian era, which ended more than 500 million years ago and well before fish evolved.

Coral reefs will be the first, but certainly not the last, major ecosystem to succumb to the Anthropocene — the new geological epoch now emerging. That is why we need an enormous reallocation of research, government and environmental effort to understand what has happened so we can respond the next time we face a disaster of this magnitude. It will be no bad thing to learn how to do such ecological engineering now.

Roger Bradbury , an ecologist, does research in resource management at Australian National University.

A version of this op-ed appeared in print on July 14, 2012, on page A17 of the New York edition with the headline: A World Without Coral Reefs.

SeaWorld/Busch Gardens

Coral Reefs Background Information

What are corals?

It’s amazing to think that something as large as the Great Barrier Reef was built by softbodied creatures smaller than your thumbnail. The animals that create reefs such as the

Great Barrier Reef are called coral polyps. Coral polyps are invertebrates—animals without a backbone. Each polyp constructs a hard cup of limestone, or calcium carbonate, around its soft body. The cup is called a corallite.

There are two kinds of corals, soft corals and stony corals. Both types of corals belong to the phylum Cnidaria (ni-DAREee- uh), a group of animals that use stinging cells to capture prey and defend themselves.

Sea anemones and jellyfishes are also cnidarians.

Basic body plan

A coral polyp’s body is a tubelike sack.

One end of its body is attached to a hard surface. The opposite end is the mouth.

Stony corals build a hard limestone cup around their bodies. They withdraw into Diving among coral reefs can be a wonderful experience. the cup during the day, and extend their mouths outside at night to feed. Surrounding the polyp’s mouth is a crown of tentacles that the polyp uses to move food to its mouth and sometimes to defend itself.

A meal fit for a polyp

Some corals eat plankton, tiny animals called zooplankton, and small fishes. Others consume organic debris. Many reef-building corals get the nutrition they need to survive from zooxanthellae, a microscopic algae that lives inside a coral polyp’s tissues.

Through photosynthesis, zooxanthellae convert carbon dioxide and water into oxygen and carbohydrates. The coral polyp uses carbohydrates as energy. The polyp also uses oxygen for respiration and in turn, returns carbon dioxide to the zooxanthellae. Zooxanthellae also recycles the waste given off by the polyp and returns amino acids.

Diving among coral reefs can be a wonderful experience.

Venomous barbs paralyze prey

The tip of each tentacle is covered with stinging cells called nematocysts. Inside these bulbous structures are coiled, venom-filled threads with tiny barbs. When triggered chemically or by something brushing against it, the capsule explodes and ejects the thread in a powerful burst of force and speed. The barb penetrates the victim's skin, and injects a potent venom that paralyzes or kills the creature. Then, the tentacles carry the prey into the polyp's mouth. There are no teeth in the polyp's mouth; the food simply passes directly into the digestive cavity inside its body.

How do corals reproduce?

In some stony corals, polyps are either male or female and produce sperm

and eggs. But other reefbuilding coral polyps are hermaphrodites both male and female at the same time. The microscopic, free-swimming larvae that hatches from the fertilized egg is called a planula. Several hours or days later, the planula settles to the bottom.

At this point in its development, a stony coral polyp begins producing a limestone shelter to protect its body

A reef takes shape

Once the polyp is established, it begins to reproduce itself through

“budding.” A small piece of the polyp may pinch off to form another individual,or a new polyp develops on a thinlayer of tissue extending out from the original polyp’s body. As a colony grows, it takes on a branched, flat, or globular shape depending on the type of coral.

When coral polyps die, their soft bodies decay, leaving only their hard calcium cups behind. New coral colonies grow on the empty limestone structures. Large coral reefs continue to develop on the skeletons of coral polyps that existed about 10,000 years ago!

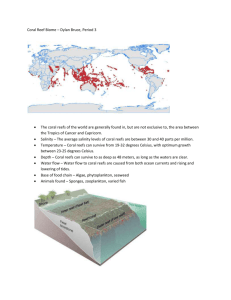

Coral reef regions

Various species of corals are found in all oceans of the world, but stony corals require certain conditions to create the vast, complex reefs. Because zooxanthellae need sunlight for photosynthesis, reefbuilding corals grow in clear, shallow water no more than 46m (150 ft.) deep. Stony coral polyps also need warm water from 20°-28°C (68°-82°F) in order to thrive. As a result, reef-building corals are scattered throughout the tropical and subtropical

Western Atlantic and.IndoPacific oceans, generally within 30°N and 30°S latitudes.

Corals create many micro-habitats for different species including fish, octopus, urchins, and anemones.

Three types of coral reefs

Many coral reefs are found near land in shallow water, because they need sunlight to thrive. There are three types of reefs: fringing, barrier, and atoll. Fringing reefs border shorelines of continents and islands in tropical seas. Barrier reefs are found farther offshore.

The Great Barrier Reef off northern Australia in the Indo-Pacific is the largest barrier reef in the world. This reef stretches more than 2,000 km (1,240 miles).

Atolls are circular- or oval-shaped reefs that surround a central lagoon. They're formed when a small volcanic island disappears below the ocean surface. The result is several low coral islands around a lagoon.

Who's at home on the reef?

A variety of colorful sponges provide shelter for fishes, shrimps, crabs, and other small animals that live on the reef. Bryozoans, microscopic invertebrates, form branching colonies over coral skeletons and reef debris, cementing the reef structure. Octopuses, shrimps, crabs, snails, and clams also call a coral reef home.

Fishes play a vital role in the reefs food web, acting as both predators and prey. Their leftover food scraps and wastes provide food or nutrients for other reef inhabitants. Reefs are

important

Corals remove and recycle carbon dioxide. Excessive amounts of this gas contribute to global warming. Reefs also shelter land from harsh ocean storms and floods. Local economies benefit from fishing opportunities and tourists attracted to coral reefs. Coral reefs are living laboratories where students and scientists can study the interrelationships of organisms and their environment.

Because the pores and channels in certain corals resemble those found in human bone, coral skeletons have been used as bone substitutes in some surgical techniques. Some evidence suggests that the coral reef might provide important medicines in the future.

Parrotfish are adapted for eating the algae inside coral.

What can harm corals and coral reefs? Parrotfish use chisel-like teeth to nibble on hard corals. These fish are herbivores and eat the algae within the coral. They grind the coral's limestone cup to get at the algae. The crownof- thorns sea star is another well-known predator of coral polyps. Large numbers of these sea stars can devastate reefs, leaving behind only the calcium carbonate skeletons.

An anemone fish peeks out from the tentacles of its anemone “home.”

Human activities also have serious affects on the world's coral reefs. Oil slicks, pesticides, garbage, and other forms of ocean pollution poison coral polyps. When fertilizer and untreated sewage wash into streams and storm drains, they end up in the ocean, where they accelerate algae growth. Unfortunately, high concentrations of algae can overwhelm and smother the polyps.

Changes to land habitats can damage coral reefs, too. When tropical forests are cut down to clear land for agriculture or homes, topsoil washes down rivers into coastal ecosystems.

Soil that settles on reefs smothers coral polyps and blocks out the sunlight needed for corals to live. Coastal development and dredging to build seaside homes, hotels, airports, and harbors can also ravage reefs.

A desire to have a bit of reef beauty at home has created a big demand for reef fish for aquariums, and shells, sponges, and coral skeletons for souvenirs. Some people pour cyanide in the water to stun the fish and make them easier to gather. However, coral polyps and other reef organisms are poisoned by this chemical. Overfishing and overcollecting also disrupt the balance of the reefs ecology. Divers and snorklers that stand on, sit on, or handle corals can injure the delicate polyps. Vigorous kicking can stir up sand that smothers polyps. Dropped boat anchors can gouge the reef and crush corals.

Coral bleaching

Coral reefs around the world are suffering from bouts of a puzzling condition that causes them to lose their coloring. Bleaching occurs when coral expels its symbiotic zooxanthellae.

Without zooxanthellae, the coral polyps have little energy available for growth or reproduction. Scientists aren't sure why bleaching occurs, but elevated water temperatures, ultraviolet radiation, and diseases or viruses affecting the zooxanthellae are some of their hypotheses.