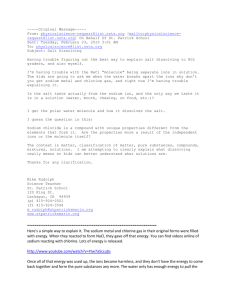

Sodium Study Chart

advertisement

Recent studies that support limiting sodium to less than 1,500 milligrams a day Study Description Conclusion Strengths Limitations Dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Appel LJ The National Academies Press 2005 A 600-plus-page book from the Institute of Medicine that analyzed research on optimal water, potassium, sodium, chloride and sulfate levels. Identified 1,500 mg/day as the adequate intake level of sodium for adults, and 2,300 mg/day as an upper level intake. One of the most complete reviews of the scientific evidence for goal-setting of potassium, sodium, chloride, sulfate and water intake. Based on a review of existing data The importance of population-wide sodium reduction as a means to prevent cardiovascular disease and stroke. A call for action from the American Heart Association. Appel LJ Circulation 2011;123:1138-1143 This advisory supplemented the AHA’s original policy paper (Lloyd-Jones DM et al, Circulation. 2010;121:586613), with a focus on justification of the AHA’s recommendation for intake of dietary sodium.-. This metaanalysis examined trends for CVD events and all-cause mortality in 7 randomized controlled trials that had tested the efficacy of a sodium reduction intervention. The scientific evidence indicates that the dietary sodium limit of <1,500 mg per day is associated with a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke and kidney disease. Experts in the basic, clinical and population sciences present a thoughtful analysis of sodium reduction as it relates to cardiovascular disease. Based on a review of existing data One trial conducted in extremely sick patients with heart failure had little or no relevance for the general population. The analysis included seven trials. Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Taylor RS Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:843-853 In five trials, the number of events was lower among those consuming less sodium. In one trial, the number of cardiovascular events was similar among participants with lower and higher sodium intakes. -more- Several authors also participated in the AHA’s overall goals paper. Because the heart failure trial included patients who already were very sick and on medications that effect sodium balance, the results can’t be applied to the general population. The remaining six trials were analyzed separately for those with high and normal blood pressure. As a consequence, the power to recognize a statistically significant effect of sodium reduction on CVD risk was extremely limited. A subsequent analysis (see He FJ, below) that excluded the heart failure trial and pooled data from the remaining trials identified a statistically significant 20 percent decrease in cardiovascular events among the lower-sodium group. Circulation/Whelton – 2 Study Name Lead Author Publication Date/Citation Long-term effects of dietary sodium reduction on cardiovascular disease outcomes: observational followup of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention (TOHP). Cook NR BMJ 2007;334:885-892 Effect of potassiumenriched salt on cardiovascular mortality and medical expenses of elderly men. Chang HY Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:1289-1296 Salt reduction lowers cardiovascular risk: meta-analysis of outcome trials. He FJ Lancet 2011;378:380-382 Description Conclusion Strengths Limitations This long-term, follow-up study included data from two previous randomized controlled clinical trials to examine the long-term effects of reduced sodium consumption on cardiovascular events among adults 30-54 with high blood pressure. This clinical trial examined the relationship between lower sodium, potassiumenriched-salt intake, medical expenditures and death from cardiovascular disease among 1,981 elderly male veterans in northern Taiwan. The paper is a quantitative assessment of the clinical trials in the study by Taylor, et. al. (see description, p. 2). Sodium reduction was associated with an approximately 25% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events. The results were analyzed according to the participant’s original randomized assignment (lower sodium intake or usual care) and events were tracked over a prolonged period of time (10-15 years), increasing the statistical power to recognize an effect of sodium reduction on CVD morbidity and mortality Incomplete follow-up rate; questionnaire format rather than direct measurement of blood pressure, weight, and sodium intake. Results demonstrated that elderly men who switched to lower sodium, potassiumenriched salt lived longer and spent less on in-patient care than men who consumed regular salt. It’s the only randomized, controlled, clinical trial comparing cardiovascular events among patients who consumed less sodium (and more potassium) compared to their counterparts who consumed their usual (high sodium) diet. Limited data, including no 24hour urine collections were obtained. After excluding a confounding trial, investigators reported a statistically significant 20 percent decrease in cardiovascular events among the lower-sodium group. See Taylor, et. al., p 2. See Taylor, et. al., p. 2. The trial only examined elderly veterans in Taiwan, who may not be similar to the general U.S. population. Consumer article: Flawed science from JAMA. Why you should take the latest sodium study with a huge grain of salt. The Nutrition Source. Harvard School of Public Health. 2012. www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/salt/jama-sodium-study-flawed/index.html Circulation/Whelton – 3 For the latest heart news, follow us on Twitter: #Heart News. ### The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association receives funding mostly from individuals. Foundations and corporations donate as well, and fund specific programs and events. Strict policies are enforced to prevent these relationships from influencing the association’s science content. Financial information for the American Heart Association, including a list of contributions from pharmaceutical companies and device manufacturers, is available at www.heart.org/corporatefunding.