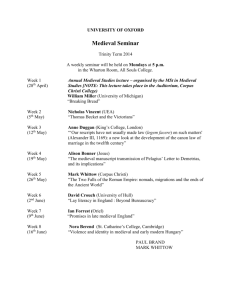

Medieval Bathing for Cleanliness, Health and Sex

advertisement

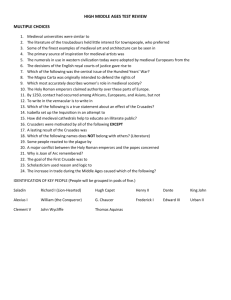

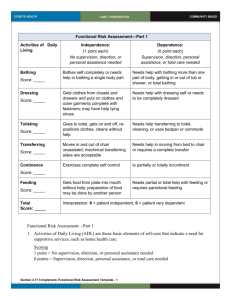

Medieval Bathing for Cleanliness, Health and Sex by Katherine Ashe There is a quite erroneous notion that medieval people didn't bathe. Some Tudors may have been proud of bathing once a month whether they needed to or not, but their ancestors had looked upon bathing as one of the sensual pleasures of life. King Henry III even had a special room for the purpose of washing his hair. The medieval approach to washing hair True, the poor had little access to bathing facilities other than the local well, and hefting buckets of water home for cooking purposes was probably quite enough of a burden. What personal washing was to be done could be done with a bowl of water. Laundry might be done in a village washhouse where once in the spring and once in the autumn stream water could be diverted to large stone tubs. Pounded lavender and soapwort made the washing compound,for soaps were not invented until the midthirteenth century. Soap was then imported from Spain and was only for the rich. Note, however, the shared linguistic root of "lavender" and "laundry," shared with the French word "lavande" and the Latin, heard in the Mass as the priest says, "Lavabo," "I will wash." Not too bad, having your laundry smell of lavender even if it's only twice a year. In cities the early mornings began with the water sellers wheeling their barrow-like barrels through the streets and selling door to door. Few houses, even of the wealthy, would have their own tubs for the immersion of a full grown person. Personal washing would be accomplished with a bowl, filled by a servant with one pitcher with very hot water from a cauldron in the hearth and another pitcher of unheated water from a barrel or stone tank in the kitchen or cellar. The desired temperature was achieved by mixing the water from the two pitchers. This arrangement would prevail for most people until the mid-nineteenth century. So much for washing, but what of bathing? To bathe, medieval men and women went to a bathhouse. Individual tubs were an option Picture a vast cellar, an undercroft with broad columns supporting the building, or multiple buildings, up above. The ceiling is low and groined and there are no windows. Iron chandeliers or candle stands, rusted to a mellow brown, bear numerous fat, white wax candles giving off a scent of honey. At one end of the room is a huge hearth hung with several cauldrons, each giving off a different perfume: attar of rose, mossy vetiver, musk or the haunting sweet aroma of civet (refined from the chokingly foul odor of the civet cat's spray to make one of the loveliest of perfumes.) The atmosphere in the low, dim room is dense with mists and laden with seductive aromas. Arranged in aisles between the sturdy columns are curtained booths, their drapes hung from tall stands to provide total privacy or, for parties of a racy nature, the curtains could be drawn back. Within each booth is a standing rack for clothing, a small table equipped with fruit, sweets, a carafe of wine and goblets, and soaps, oils and strigils (which we will discuss below.) And the central feature of the booth is of course the tub, made of wood like a huge bucket and equipped with seats inside so that the bathers may be immersed up to their necks when sitting. A friend of mine recently bought just such a tub from Russia, where apparently such bathing has continued in some places, sans plumbing, to this day. Such a tub will accommodate at least two people. Or one could share… If this sounds a bit like the modern "hot tub" and the pleasures of the "fast set" in places like Las Vegas, you've got it about right. While such bathhouses were where one went to seriously wash, they were also popular with married couples with sensual tastes, were notorious trysting places for clandestine lovers and were a favored workplace for courtesans. Priests and street corner preaching monks inveighed against them as halls of sin and depravity, and seem to have succeeded in reducing their presence until their reincarnation (with plumbing in place of hot and cold running servants) in modern times. Most illustrations from medieval manuscripts disapprovingly depict the bathhouse of the brothel variety. What of bathing for health? Spas developed all over the Roman empire, wherever there were hot springs and waters with minerals thought to heal or restore health and vitality. Many of these spas have never been out of business since Roman times. Probably everyone knows of Bath and its Pump Room, made the height of fashion by Beau Brummel in the early 19th century. So I'm going to describe a somewhat less grand, and more close to ancient usage, spa, that of Dax, in England's medieval dukedom of Gascony in southwestern France. In medieval times Dax was especially busy, as it was located on the pilgrim route to Santiago de Compostella. Hence it was richly supplied with jewelers' shops to make settings for theseashells which were the proud souvenirs of anyone who had reached Compostella. Today the elegant shops lining Dax's main streets offera wonderful array of toys for grannies to bring back to their grandchildren, and the most beautiful candy shops perhaps in the world: row after row of footed crystal dishes heaped with chocolates wrapped in gold foil, each variety labeled with a tiny reproduction of a painting by Vermeer, Rubens, Rembrandt, etc.Dax, as it always has been, is a place for the rich and elderly to recover, indulge themselves, and think pleasantly of those back home. And the bathing there? The bathers, monkishly sandaled and bundled in hooded white robes as they always have been, hurry through the streets to the bath. Which could hardly be more different from the undercroft bathhouse. Along the main street is a marble trough the rear wall of which has a row of Roman bronze lion heads with open mouths, each spewing a stream of hot water. Above the wall of these small but magnificent public spigots rise the weatheredcolumns of the Roman bath, at the street front of a rectangular, roofless temple-like structure. Where the floor of this temple of health would be is the pool, steaming with water from natural hot springs. A crowd of bathers, immersed amid the wreathing steam, soak in hopes of curing everything from rheumatism to varicose veins. Pilgrims too are still there, soaking their blistered feet after their trudge across the Pyrenees and back again. The bath at Dax today Strigils? I mentioned that soap was a Spanish invention of the mid-thirteenth century, so it was probably available at Dax very soon after its first appearance in Spain. But how did people wash before that? They rubbed themselves with scented oils and then scraped off the oils, dirt and shedding skin with a strigil, which looks rather like a marriage of an old fashioned straight razor with a butter knife. With the sharpness of the latter. The heat of the bath caused pores to open, helping to expel dirt, and the strigil scraped it away, leaving the skin smooth, clean, oiled and scented. A Roman strigil ----This was how people bathed in ancient Rome, this was how they bathed in Europe - until the invention of soap, in Spain, which may or may not be an improvement when dry skin is taken into consideration. However, the new Spanish luxury took over and made the strigil obsolete. Other means of hygiene associated with Spain were not so universally embraced. Gaius ValeriusCatullus, in about 50 BC, pokes a jibe at a Spanish customs of cleanliness in a poem addressed to Egnatius, a young Iberian gentleman overly given to flashing his brilliant smile. Catullus claims he would not be offended by such smiles from people of any of a number of other nationalities, but Egnatius is a Spaniard, and in Spain, according to Catullus, bright, clean teeth were achieved through the use of one's urine. If this seems shocking, we might take note that synthetic urine (urea) is an ingredient in many modern compounds. No doubt the synthetic variety is to be preferred. Cleanliness has meant different things to different peoples at different times. It has always been considered a virtue, in whatever form was current, except of course when it was pursued with excessive sensual gusto. Then it could be a sin. The spa has twothousand years of history as a treat for the rich and a hope for the sick. And lavender still scents some of our laundry detergents. Katherine Ashe is the author of the Montfort series, on the life of the man who founded England's parliament in the year 1258. Montfort The Early Years 1229 to 1243; Montfort The Viceroy 1243 to 1253; Montfort The Revolutionary 1253 to 1260 and Montfort The Angel with the Sword are available from Amazon.