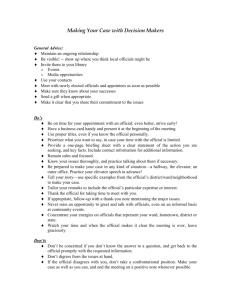

Political- administrative interface in the inclusive government

advertisement

Paper to be presented at the Multinational Conference on Improving the Quality of Public Services and Public Management (27-29 June 2011) Title The bureaucracy under the inclusive government in Zimbabwe Author Ricky Munyaradzi Mukonza Tshwane University of Technology (South Africa) Department of Public Management Contact Details Cell: +27745037780 Email addresses: tsanomunya@yahoo.com Or ricky.mukonza@gmail.com Abstract In the recent past African countries that experienced disputed elections such as Kenya and Zimbabwe ended up with inclusive governments, also commonly referred to as governments of national unity (GNUs). A lot has been written on the subject and most of the literature generated focuses on the merits and demerits of this political phenomenon in general terms. This paper however, seeks to analyze how top public servants in Zimbabwe have reacted to the change in the country’s political terrain brought about by the inclusive government. It is a given in public administration and political theory that the administrative stratum of government follows the direction given by the political stratum. The paper, however argues that top public servants in Zimbabwe have taken time to transform to meet to the demands of the new political order and this has had a negative impact on the operations of the inclusive government, thus to service delivery. It is further contended that until there is harmony between political and administrative heads, particularly in ministries manned by former opposition political parties, squabbles will continue to bedevil the inclusive government and service delivery will not improve as anticipated. The notion of a politically neutral public service is interrogated to ascertain whether it is feasible in Zimbabwe or elsewhere in the world for that matter. A qualitative research approach is employed through the analysis of different texts on and by the inclusive government and on the basis of the findings, a conclusion is reached. Experiences from other countries will also be utilized to further give weight to the arguments. A history of public service as well as a survey of the constitutional and legislative frameworks in Zimbabwe is given to give context to the arguments advanced in this paper. Introduction The signing of a power sharing agreement in 2008 between the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU PF) and the two formations of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) resulted in the formation of the inclusive government in February 2009. This development brought about fundamental changes in the politics of Zimbabwe. Since 1980 when Zimbabwe attained independence from colonial rule to 2008, the country’s political space, particularly in government has been dominated by ZANU (PF). The inclusive government meant ZANU (PF) had to share governmental power on almost equal terms with the two MDC formations. All this was done on the basis of a power sharing document, the Global Political Agreement (GPA) which inter alia, redistributes power among the different political players in the inclusive government. The GPA also implores all players in government work together for the benefit of the people of Zimbabwe. The paper among other things explores one of the key variables in the policy process and ultimately in service delivery namely the relationship between the bureaucrats and political officials. It is argued that the relations particularly between top public officials in some ministries manned by MDC ministers are poor and this impacts negatively on service delivery and thus militates against the letter and spirit of the GPA. The paper further interrogates whether the idea of a politically neutral public servant is possible under the inclusive government or any other government system. Lastly, recommendations are proffered on how best relations can be improved between political and administrative heads in the inclusive government. As a point of departure, an attempt is made to explain and contextualize the term top public official. Top public officials explained The terms top public official, top bureaucrat and top civil servant are sometimes used interchangeably as if they mean the same. For the purpose of this paper it is important to interrogate the meanings attached to all the three for clarity. Venter and Landsberg (2011:82) define public officials as people manning government offices; these could be employed by either the national or provincial governments of a country. Put in other words it refers to a component of a state’s management and public administrative apparatus which is sometimes referred to as the bureaucracy (Venter and Landsberg, 2011:82). It therefore can be derived that top public officials are those tasked with heading the different government departments. Closely linked with top public official is the term top bureaucrat. It might be plausible to trace the origins of the word bureaucracy. The word is derived from a compound Greek word bureau which means rule and kraten which refers to table. According to Hanekom and Thornhill (1983:117) the word bureaucracy conjures up different images but in its original sense means rule from the table and was used to refer to rule by public officials. Venter and Landsberg (2011:84) understand bureaucrat, which is a derivative of bureaucracy to refer to non-elected, professional staff and normally life long government employees. From the explanations provided, it seems the two terms means one and the same and any attempt to differentiate them has no real value. In some cases top public officials are referred to as top civil servants. Cloete (1995:20) defines civil servant as members of the public service. It is however important to observe that top civil servant refer to top public servants other than uniformed forces appointees In the context of this paper, top public official refers to administrative heads in government departments or ministries and assume different titles from one country to another. In Zimbabwe, they are referred to as secretaries and differ from South Africa where they are called Director Generals while in Britain they are known as permanent secretaries. Irrespective of these semantic differences these top officials are in most cases the accounting officers of the entities they head. It is these functionaries who are the centre of discussion of this paper. Before focusing on them, an overview of the history of Zimbabwe’s public service is presented to give context to proceeding discussions. A historical overview of public service in Zimbabwe The advent of independence in 1980 presented the government of Zimbabwe with a number of challenges. From a public administration perspective transformation of the public service delivery system from a settler colonial administration that favoured a white minority to one that accommodates the majority black population was a priority (Chimhowu, 2010: 111). The Growth and Equity document and the Three Year Transitional Plan outlined government’s vision and agenda to of a socialist transformation in the society. One of the major challenges faced at the point was shortage of skills, particularly at the strategic levels of government. Jenkins (1997:581) argues that new Black ministers whose recommendations were critical in the appointment of permanent secretaries were not willing to work with top public servants from the previous government. The main reason was suspicion that these top officials were likely to sabotage government policies and programmes. Agere (1997:86) cites the example of the Ministry of Transport where resistance was demonstrated after the appointment of a black minister. This prompted the minister to go ahead and appoint a black permanent secretary and in other key positions in the ministry (Agere, 1997:86). The approach had its own problems; firstly in most cases the appointees did not have requisite skills to lead critical government projects. Secondly, where they had skills they did not have the experience to quickly fit into the vision of the new government. Although the government organised training programmes to assist public servants acquaint them with how government operated and to understand the rules and procedures guiding service delivery, still there were serious challenges in the implementation of government policies in key government sectors (Chimhowu, 2010: 111). Towards the end of the first decade of black rule in Zimbabwe, government through the 1989 Public Service Commission Kavran Report identified some of its weaknesses. The Report, inter alia, revealed a bureaucracy characterized by ; lack of a performance management culture, arrogance, poor work attitudes, high staff turnover, a bloated and secretive (Chimhowu, 2010: 112). The other important findings were that there was general poor communication of decisions from top management to the lower strata of government as well as to the general public and there was duplication of functions. In other words the Report painted a gloomy picture of the Zimbabwe’s public service at the time. However what the Report did not say but is apparent in its contents is that there was general lack of leadership in the public service. The state of affairs portrayed by the Report called for reforms in the country’s public service. Nevertheless, no reforms were introduced until 1997 arising from a Customer Satisfaction Survey in 1996 showed that there were no changes in the manner in which the bureaucracy behaved. The situation was worsened by the negative effects brought about by the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP) introduced in the early 1990s. From 1996 to 2002 reforms in the public service were focused on making it result-oriented, in other words, maintain expenditure while at the same time address socio-economic challenges such as poverty, unemployment and service delivery as much as possible (Chimhowu,2010:114). Efforts were made to borrow private sector approaches such as entrepreneurship, this was combined with restructuring which focused on streamlining functions to eliminate duplication as well as achieve speedy decision making by compressing the top level grades (Chimhowu, 2010:114). Between 2002 and 2008, the socio- economic and political crisis that hit the country did not spare the public sector. This however did not stop further public service reforms from being instituted and this time they were aimed at enhancing performance, service delivery and good governance (Chimhowu, 2010:115). Chimhowu (2010:115) further states that values such as integrity, honesty and ethical standards diminished in the public sector particularly from 2003 onwards as a result of the economic and political crisis. This prompted government to reform its ethical approach in 2005 and this included, inter alia, performance agreements with administrative heads. Administrative heads were in turn expected to conduct performance reviews for their staff to ensure that objectives of their ministries are met. Leadership was also an important component in the public sector reform. In that regard, executive management programmes were introduced at the Zimbabwe Institute of Administration and Management (ZIPAM) and these were targeted at middle managers and above (Chimhowu, 2010:115). A brief discussion on the constitutional and legislative framework guiding top public officials in Zimbabwe follows. Constitutional and legislative framework for top public officials Legislatively and constitutionally, top public officials in Zimbabwe are guided by the Constitution of Zimbabwe, 1979 and the Public Service Act, 1995. According to the Public Service Act, 1995, top public officials are referred to as secretaries and they are heads of their respective ministries. It must be noted that many official and non-official documents including the Global Political Agreement and different Southern African Development Community (SADC) Communiques wrongly refer to them as permanent secretaries. According to a Member of Parliament, Mr. Felix Magalela, the use of the term permanent secretary, though wrongly so, carries connotations of officials who are permanently employed by government irrespective of their performance (http://zimvest.com/there-are-no-E2%80%98%&permanent-secretaries accessed on 03/05/2011). Constitutionally, Section 20.1.7 of the Constitution of Zimbabwe, 1979 as amended through Constitutional Amendment 19 gives the President power to appoint (permanent) secretaries. This position has however been contested by the MDC-Tsvangirai formation which argues that all top government positions including the appointment of secretaries, ambassadors and Provincial Governors should be done with the consultation of all the Principals in the GPA, that is, all the leaders of political parties in the agreement. In the past, the President appointed top public officials with recommendations from the minister of the concerned ministry and in consultation with the Public Service Commission (Agere, 1997:86). With the brief overview of the legislative and constitutional framework, the paper proceeds to look at the politicaladministrative interface in the inclusive government. Political- administrative interface in the inclusive government The importance of the relationship between top public officials and political heads in the execution of government responsibilities can not be overemphasized .Thornhill and Hanekom (1995:2) aptly put across the point when they wrote “An important phenomenon affecting the administration of public affairs is the relationship between the political head of a state department – the minister and top public officials his/ her department…”. In general terms general roles of the Minister are inter alia; providing political direction, leadership, motivation, control and accountability for the department they are in charge of. On the other hand public managers act as advisors to ministers with regard to technical and political matters, policy and resource management (Thornhill and Hanekom, 1995:2). The above implies that top public officials need to strongly identify with the policies of the government they serve. Given the above background it is important that an analysis of the relationships between ministers and top public officials in Zimbabwe’s inclusive government be done. This is particularly important in ministries manned by the Movement for Democratic Change. The coming into being of the inclusive government in Zimbabwe brought in some changes on the political landscape notably the ministers from the two formations of the Movement for Democratic Change. The ministers, some of whom did not have experience in government were faced with the challenge of working with experienced top public officials appointed from the previous government. The initial unilateral appointment of these top officials by the President without prior consultation with Principals from the other political parties as prescribed by the Global Political Agreement did not inspire a spirit of trust and cooperation necessary for good working relations between ministers and their top officials. The mistrust partly explains the widely reported disagreements that rocked the inclusive government on the appointment of (permanent) secretaries. The argument put forward by the Movement for Democratic Change, particularly the formation led by Morgan Tsvangirai is that (Permanent) Secretaries in MDC led ministries must be appointed by the concerned party. Logically, this would lead to a workable relationship between the permanent secretaries and ministers and subsequently enhance implementation of government policies and service delivery. In resolving the issue, the parties agreed to let the appointed permanent secretaries serve their terms. The mistrust and power struggles between some MDC ministers and their permanent secretaries proved retrogressive for the inclusive government faced by the challenges of transforming the economy, achieving political stability, spearheading constitutional reform and delivery of services. A prominent example of a struggle between an MDC minister and his permanent secretary was exposed by the Court case between a company bidding to supply electricity meters, Solhart Zimbabwe and the Minister for Energy and Power Development. The Minister in his opposing affidavit wrote “… in any event I need to set the record straight. I as the Minister for Energy and Power Development set policy and directions and not the permanent secretary. He (permanent secretary) can only write concerning parastatals on my say-so, not on his own initiative. He has no part except what I ask him to do…” (News Day, 2011:1). Firstly, what is striking in the statement is the tone with which the Minister uses in reference to his top public official. The tone does not reflect a close relationship between the concerned minister and the (permanent) secretary. Secondly, there appears to be a confusion of the roles of the two. The Ministers appears to be at pains to clarify his duties and authority and the question is; if there is a good relationship between him and his secretary, why could this not be done in the offices? The other example of political-administrative discord in the inclusive government is evident when the secretary of Information and Publicity, George Charamba publicly castigated the Prime Minister for signing a bilateral agreement with the South Korean government (CISOMM, 2010:17). The former argued that the later did not have jurisdiction to preside over such matters. Although in this case the secretary could have been right in line with the GPA, the issue was supposed to have been handled by the President of the country, it is was against protocol for the secretary to publicly criticize the Prime Minister. This is because according the same GPA, the Prime Minister is the head of government business which means, not only is the Prime Minister a superior to the secretaries but also to the ministers in the inclusive government. The International Crisis Group (ICG) (2010:5) states that (permanent) secretaries have taken advantage of the inexperience of MDC ministers to acquire free reign in determining the pace and implementation of government policies and decisions. The ICG (2010:6) further cites example in the Ministry of Education and Ministry of Public Service where the (Permanent) Secretaries overturned decisions with regard to new school and structures and manpower audit of civil servants respectively. In an interview capture by the ZimOnline, 27 August 2009 the Minister of Education alluded to a perception of two centres of power in his ministry (him on one side and his secretary on the other), however he attributed this to the process of transition that the country was undergoing (Interview: ‘Education sector still very fragile’ Available on: httpwebcahe.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:TrkdF8jkJfAJ.www.zimonline.co.zw accessed on 27/05/2011) It is however worth to note that conflicts between political and administrative heads is not only confined to the inclusive government. The fall out between the then Minister of Information and Publicity, Jonathan Moyo and his secretary, Charamba in 2005 is a case in point. In this case the later boasted of his experience in government which spanned over two decades against the minister’s less than five. Closely linked to this example is that between the then Minister of Agriculture, Joseph Made and his secretary, Pazvakavambwa who had a fall out as a result of disagreements on a deal that led to the purchase of substandard fertilizer from a South African company (Chimhete, 2005:1). It is important to explain why some of these conflicts arise in the political administrative interface. Firstly, the issues of expertise in which in most cases top public officials are more knowledgeable about a ministry’s line functions than their political heads (this is not always the case). According to Thornhill and Hanekom (1995:28) while ministers provide political direction and leadership to officials and the public, public officials weigh in with their expertise on policy and management issues. Secondly, public officials tend to be more experienced on government business than their political superior. This gives them an advantage in solving what could be complex matters and if there is poor rapport between the top official and the minister conflicts could arise. Lastly the personality variable particularly in policy making can not be under estimated. In some cases the minister in spite of his shortcomings might want to be seen as the leader of the process which might not augur well with his or her top public official thus resulting in a clash. The importance of a good relationship between administrative and political heads in government is important for good policies and ultimately service delivery. This is particularly so given the important roles which both play in the running of ministries. Examples have been cited of poor working relations between administrative and political heads in the inclusive government and the period before it with the aim to show how this has derailed the smooth operations of government for the benefit of the people of Zimbabwe. Suggestions for politically neutral top public servants have been suggested as a solution to these conflicts between secretaries and ministers in the inclusive government, it is therefore critical to interrogate the possibility of having politically neutral top public servants. Politically neutral public servant: A myth or reality? The challenges that rocked the appointment of permanent secretaries in Zimbabwe prompted suggestions for politically neutral public servants. When the matter was resolved, Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai in his statement remarked “… We do not believe that civil servants should be appointed on a partisan basis, so there will be no civil servant from MDC or ZANU PF. Any civil servant who participates in partisan politics will have no place in our public service, and I urge the Minister of Public Service to ensure that the appropriate measures are put in place to that effect” (Prime Minister, 2009:1). In the statement, the Prime Minister appears to envisage a public service that is neutral in its operation. The question is whether or not neutrality is possible particularly for top public servants given the environment within which they execute their duties. Dolan (2003) as cited in Kalema (2009:550) alludes that the concept that public officials must serve members of the public impartially or should be recruited on the basis of competency rather than any partial considerations is neither new nor unique. The point is further given weight by a manuscript on the ancient Egyptian civil service which advises public officials to: Be courteous and tactful as well as hones and diligent: all your doings are publicly known and must therefore be beyond complaint or criticism. Be absolutely impartial: always give reason for refusing a plea: complainants like a kindly hearing even more than plea. Preserve dignity but avoid inspiring fear. Be an artist in words, that you may be successful strong, for the tongue is a sword (Civil service Manuscript from Egyptian Pharaohs – c. 3000 B.C. as cited in Kalema, 2009:550). Furthermore, works of early Greek philosophers such as Aristotle in Politics and Plato in Republic emphasise the importance of impartiality and competence in public service. According to O’Toole (2006:3) these philosophers were advocating for an ideal public official who regards the interests of the whole society as being the guiding influence in public decision making that their personal or other partial interests are to be set aside. Plato in the Republic succinctly puts the idea, he refers to holders of public officers as “philosopher rulers” who ‘ will be those who, when we look at the whole course of their lives, are found to be full of zeal to do whatever they believed to good for the commonwealth and never willing to act against its interest” (O’Toole, 2006:3). The above shows that early philosophers viewed politically neutral and duty conscious public servants as key in advancing societal goals. European and American experience Influenced by early philosophers, the principle of neutrality is argued to have evolved in the Western industrial economy and is widely associated with the emergence of multiparty politics (Kalema, 2009:550). Page (1992) as cited in Kalema (2009:550) asserts that Britain, France and Germany instituted reforms in their recruitment systems to include examinations. The need for neutrality and impartially in public servants was dire in England and later in America as ruling parties lost elections to opposition parties. The situation required a non-political and more permanent civil service for stability and continuity of governments (Paris, 1969:36). According to Dang (1966:67) in France the need for separation of administration and politics has long been entrenched in the French political-administrative culture and is further supported by the old French adage “le government change, la’ administration reste” , meaning that government change but the administration remains the same. In Britain, the Northcote-Trevelyn Report of 1854 influenced key changes in Britain’s public service including, recruitment to civil service based on merit and nonpartisan, permanent civil service (Whincop, 2002 as cited in Kalema, 2009:550). O’Toole (2006:194) however dismisses the notion of portraying public servants in Europe as neutral, disinterested and anonymous saying it was only an ideal. He further contends that public officials were only human beings who had ambitions and aspirations like all people and they actually viewed their jobs as platforms to achieve these aspirations (O’ Toole, 2006:195). Experiences in Zimbabwe and South Africa On paper, Zimbabwe envisages a merit based and non-political public service and this is reflected in Section 18 of the Public Service Act, 1995 which reads; The Commission shall— (a) have regard to the merit principle, that is, the principle that preference should be given to the person who, in the Commission’s opinion, is the most efficient and suitable for appointment to the office, post or grade concerned; and (b) ensure that there is no discrimination on the ground of race, tribe, place of origin, political opinions, colour, creed, gender or physical disability. The above applies to members of the public service other than secretaries. According to the GPA, permanent secretaries are appointed by the President of the Republic, this makes them political appointees. The political nature of top public servants explains why a majority of them end up occupying political positions in government. Examples include, current Minister of Justice Patrick Chinamasa who was once a secretary in the ministry, former Minister of Labour and Manpower Development, July Moyo who was once a secretary in the same ministry and the current Minister of Higher Education, Stanely Mudenge is a former secretary in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In fact a closer look at the current ZANU (PF) cabinet ministers reveals that a majority of them were once occupants of top administrative positions in government. This gives credence to O’Toole (2006:195) ‘s assertion that public officials were only human beings who had ambitions and aspirations like all people and they actually viewed their jobs as platforms to achieve these aspirations South Africa has adopted a combination of British, French and American systems both during and post apartheid. Kalema (2009:551) however states that although top public officials adhered to liberal principles, they were highly politicized. The post of Director General was held by National Party members only (Venter and Landsberg, 2011:85). In terms of policy, post apartheid South African government envisaged a public service that is “faithful to the Constitution, non-partisan and loyal to the government of the day” (Republic of South Africa, 1995:9). South Africa has also established a neutral body, the Public Service Commission to deal with personnel issues in the public service. Currently appointment of top public officials in South Africa is a prerogative of the President. It is however worth to note that this approach caused disagreements between former President Thabo Mbeki and the then Minister of Home Affairs Buthelezi (Kalema, 2009:551). The latter did not agree to the Director General appointed to his department. Kalema (2009:551) citing Esau (1997) concludes that public servants in South Africa are political appointees who are expected to play neutral roles. Conclusion To conclude, reviewed literature has shown that there are challenges in the relations between some ministers and there top public officials in the inclusive government. This has the potential to derail progress in the attainment of the goals set for the inclusive government. It has also been argued that politically neutral top public officials exist in a utopian world; in the real world they are political. The nature of their roles, particularly in interacting with elected political officials requires that they engage in political activities. Peters (1995:91) argues for a mixture of political disposition and administrative talent in top public officials and he refers this as responsive competence as opposed to neutral competence. The major question on political versus merit appointment is that of degree, in other words, the extent to which political appointments can be made (Peters, 1995:91). In finding the right mixture, the question of what must be done to ensure that relations between ministers and top public official effectiveness of government, needs to be addressed. Given the conflicts identified between ministers and top public officials in the inclusive government, it is recommended that the President reverts to the earlier system of consulting with concerned ministers when appointing administrative heads. This will foster a spirit of trust that is necessary for the two to work together in advancing the goals of the inclusive government. The danger of this approach however is that it might deteriorate into a political patronage system in which top public officials act as the minister pleases instead of giving their expert advice as objectively as is required in performing their roles. The inclusive government is faced with a mammoth task of transforming the Zimbabwean socio-economic and political environment for better and this requires unity of purpose among political and administrative heads. References Agere, S. 1997. The management of interface among the policy and administrative leadership in Air Zimbabwe. Asian Journal of Public Administration 19 (1) 86-101 Beetham, D.1987. Bureaucracy. Stratford: Open University Press Peters, B. G. 1995. The Politics of Bureaucracy. London: Longman Group Ltd Jenkins, C. 1997. Politics of economic policy-making in Zimbabwe. The Journal of Modern African Studies 35 (5) 575-602 Chimhowu, A. 2010. Moving forward in Zimbabwe: Reducing poverty and promoting growth. [Online]. University of Manchester. Available from: www.bwpi.manchester.ac.uk/moving forward in zimbabwe1 Chapter 10.pdf. [Accessed on 03/05/2011] O’Toole, B. J. 2006. The ideal public service: Reflections on the higher civil service in Britain. New York: Routledge Republic of South Africa. 1995. White Paper on Public Service Transformation. Cape Town: Government Printers Zimbabwe.1995. Public Service Act. Harare: Government Printers Zimbabwe. 1979. Constitution of the Republic of Zimbabwe, 1979 (Including Amendment No. 19). Harare: Government Printers Hanekom, S.X and Thornhill, C. 1983. Public Administration in contemporary society: A South African perspective. Pretoria: Macmillan South Africa (Pty) Ltd Cloete, J.J.N. 1995. Public Administration Glossary. Pretoria: van Schaick Paris, H. 1969. Constitutional Bureaucracy. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. Wallace, M., Fertig, M. and Schneller, E. 2007. Managing change in the public services. Blackwell Civil Society Monitoring Mechanism (CISOMM), 2010. Six month shadow report on the performance of the inclusive government of Zimbabwe. Harare International Crisis Group (ICG). 2010. Zimbabwe: Political and Security Challenges to Transition. Africa Briefing (70). Harare Zimbabwe. Prime Minister. 2009. Statement on the Implementation of the Global Political Agreement and The Outstanding Issues. Harare. Dang, N. 1965. Vietnam: Politics and Public Administration. Honolin East-West Centre Press Venter, A. and Landsberg, C. 2011. Government and politics in South Africa. Pretoria: van Schaik, Gildenhuys, J. S. H. and Knipe, A. 2000. The organisation of government: An introduction. Pretoria: van Schaik, Kalema, R. 2009. Issues in the transformation of the South Africa bureaucracy. Journal of Public Administration, Volume 44 (3.1), October: 546-556. Thornhill, C. and Hanekom, S.X. 1995. The Public Sector Manager. Butterworth Publishers Pty Ltd, Pretoria Chimhete, C. 2005. Fertilizer saga: “Fire me and I will spill the beans”. The Standard, November.26:1 News Day. 2011. Mangoma defends Zesa meter tender award. News Day, March. 30:1 Interview: ‘Education sector still very fragile’ Available on: httpwebcahe.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:TrkdF8jkJfAJ.www.zimonline.co.zw accessed on 27/05/2011c http://zimvest.com/there-are-no-E2%80%98%&permanent-secretaries 03/05/2011. accessed on