Running Head: IV INFILTRATION/EXTRAVASATION 1

advertisement

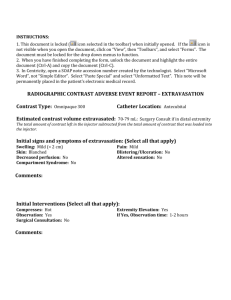

Running Head: IV INFILTRATION/EXTRAVASATION Recognizing and Treating IV Infiltration/Extravasation in Neonate and Pediatric Patients Sydonie J Stock Ferris State University 1 RECOGNIZING & TREATING IV INFILTRATION/EXTRAVASATION IN NEONATE AND PEDIATRIC PATIENTS 2 Recognizing and Treating IV Infiltration/Extravasation in Neonate and Pediatric Patients Intravenous administration is a widely used method of managing medication in a hospital setting. It is necessary to use an IV when a patient needs a certain medicine to be administered over a period of time. This method is not without its risks, however. Two problems that could occur while a patient is receiving IV medication are infiltration and extravasation. Infiltration/Extravasation Before a Nurse or any healthcare provider can recognize a possible problem with an intravenous administration, she or he needs to know what is considered a ‘problem’. Extravasation and infiltration are two issues that can occur while administering medications via an IV. Extravasation, as defined by the online medical dictionary Medline Plus, is when fluid passes through the “proper vessel or channel” by either infiltration or effusion. Infiltration is defined as permeation by “penetrating [a vessel’s] pores or interstices” (Medline Plus, 2012). In simpler terms, both extravasation and infiltration occur when the fluid that is supposed to be added to a vein starts to collect in the tissues outside the vein. Amjad, et al, and the study performed by Rodica Simona further clarifies that the “major difference between infiltration and extravasation is the type of fluid infused”. Infiltrations are when “nonvesicant fluids like sterile saline” seep through the wall of the vein and into the surrounding tissue. Extravasation is more severe as it involves “vesicant solutions like dopamine, caffeine, and many chemotherapeutic agents” (Amjad, et al, 2011). Risk Factors According to the case study performed by Laura Kuensting, RN “premature infants, neonates, and young children” are more likely to sustain injury from extravasation than an adult. It is estimated that 11% of neonates in a neonatal intensive care unit experience extravasation. In RECOGNIZING & TREATING IV INFILTRATION/EXTRAVASATION IN NEONATE AND PEDIATRIC PATIENTS 3 44% of those cases the injury is so extreme that the effected skin starts to “slough” off (Kuensting, 2010). In the study performed by Amjad, et al, it was stated that “up to 78% of IVs [in NICU] are estimated to become infiltrated.” His study also reiterated the 11% extravasation estimate. Because infants and neonates have “fragile veins” and more the catheter is not as easily stabilized, they will have more complications due to infiltration (Amjad, et al, 2011) (Simona, 2012). Though adults may also suffer from infiltration, it is usually less severe. Since adults can voice their concerns over new or increased pain, the infiltration is caught early. Infants, especially if they are intubated, cannot make their needs as well known (Amjad, et al. 2011). Harmful Effects Kuensting states that the harmful effects of extravasation or infiltration can vary depending on multiple factors. These factors include “the agent” or drug being administered, the concentration of the drug or its “potency” (Amjad, et al, 2011), the amount of the drug, and how long the drug was infiltrating or seeping into the tissue before being treated. In the case study, the six day old neonate was estimated to have extravasation for up to eight hours before it was noticed (Kuensting, 2010). Tissue necrosis, or tissue death, is a possible effect of infiltration or extravasation. Other less severe but still unwanted effects include pain in the affected area, infection, prolonged hospital stay and increased cost, and even disfigurement (Kuensting, 2010). Extravasation can cause blisters or chemical burns due to the types of liquid collecting in the tissues (Amjad, et al, 2011). RECOGNIZING & TREATING IV INFILTRATION/EXTRAVASATION IN NEONATE AND PEDIATRIC PATIENTS 4 Assessment - Infiltration Grading Scale A widely accepted grading scale was developed by the Infusion Nurses Society (INS) in 2006 and can be reviewed in Appendix A. Amjad, et al, found that the scales currently in use do not take into account the size of the patient. For example, swelling found on an adult that measures two inches involves only a small portion of the body. However, two inches on an infant or neonate could be involving half the foot or forearm (Amjad, et al, 2011) (Simona, 2012). They created a grading scale that “more accurately represents concerns relating to infant and neonatal populations” (Amjad, et al, 2011). This scale can also be found in Appendix A. In Simona’s study, “a group of IV experts and staff nurses from a large universityaffiliated pediatric tertiary care facility” analyzed the INS Grading Scale and made adjustments to the clinical criteria to better describe pediatric patients (Simona, 2012). This scale can be seen in Appendix A. Treatment Throughout the three studies examined, it has been established that there are many methods of treating injuries due to infiltration and extravasation in pediatric and neonate patients. Hyaluronidase Enzyme In the case with the neonate and extravasation, the physician ordered a subcutaneous administration of 1 mL of the hyaluronidase enzyme, rHuPH20. Hyaluronic acid is the substance that holds tissue together. By adding hyaluronidase to the body, tissues are not being held so tightly because the new drug ‘distracts’ the hyaluronic acid from its job. This means that the medication that has infiltrated into the tissue can be reabsorbed into the veins more easily (Kuensting, 2010). RECOGNIZING & TREATING IV INFILTRATION/EXTRAVASATION IN NEONATE AND PEDIATRIC PATIENTS 5 recombinant human hyaluronidase vs. animal-derived hyaluronidase In Kuensting’s case study, the physician ordered rHuPH20, which is made from human recombinant-DNA. There are several reasons why rHuPH20 is preferable over the animalderived version. Use of the animal-derived hyaluronidase has been known to cause allergic reactions, sometimes resulting in anaphylaxis. Also, using the animal-derived version required several small injections throughout the affected area, whereas the recombinant human version requires one injection with favorable outcomes (Kuensting, 2010). Less Invasive Interventions According to Amjad, et al, “a multidisciplinary team consisting of a clinical nurse specialist, a clinical pharmacist for an NICU, and a pediatric plastic surgeon” met and developed a treatment plan that is less invasive than the current practices. Using the grading scale developed by Amjad, et al, they formed an algorithm, or flow chart, depicting the actions one should take given a certain scenario (Amjad, et al, 2011). This flow chart can be found in Appendix B. Theory The theory I believe most relates to this topic is the Adaptation Theory. Adaptation is defined in our textbook as “the adjustment of living matter to other living things and to environmental conditions” (Taylor, et al, 2007). Like the body continually adjusting to internal and environmental changes, so must healthcare adjust to changes in established best practice. Conclusion From examining these three articles, written by Kuensting, Simona, and Amjad, et al, two key points can be made relating to neonatal, infant, and pediatric IV infiltration and extravasation. First, infiltration and extravasation are more likely to have deleterious effects on RECOGNIZING & TREATING IV INFILTRATION/EXTRAVASATION IN NEONATE AND PEDIATRIC PATIENTS 6 patients of this age range than on adults. Second, there needs to be a uniform grading scale tailored to patients of smaller size. Further study in pediatric, infant, and neonate IV infiltration and extravasation will be needed to determine, more precisely, how to best identify and treat the problem. “More widespread understanding of the causes of infiltration and steps in its progression will allow for better treatment through prevention and less traumatic, less expensive hospital stays” (Amjad, et al, 2011). RECOGNIZING & TREATING IV INFILTRATION/EXTRAVASATION IN NEONATE AND PEDIATRIC PATIENTS Appendix A Infusion Nurses Society (Amjad, et al, 2011) Specified for neonatal and infant patients (Amjad, et al, 2011) 7 RECOGNIZING & TREATING IV INFILTRATION/EXTRAVASATION IN NEONATE AND PEDIATRIC PATIENTS INS Grading Scale modified for pediatric patients (Simona, 2012) 8 RECOGNIZING & TREATING IV INFILTRATION/EXTRAVASATION IN NEONATE AND PEDIATRIC PATIENTS Appendix B Less Invasive Intervention (Amjad, et al, 2011) 9 RECOGNIZING & TREATING IV INFILTRATION/EXTRAVASATION IN NEONATE AND PEDIATRIC PATIENTS 10 References Amjad, I., Murphy, T., Nylander-Housholder, L., & Ranft, A. (2011). doi:10.1097/NAN.0b013e31821da1b3. A new approach to management of intravenous infiltration in pediatric patients: pathophysiology, classification, and treatment. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 34(4), 242-249. Retrieved November 20, 2012, from CINAHL database. Kuensting, L. (2010). doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2010.02.001. Treatment of intravenous infiltration in a neonate. Journal of Pediatric Healthcare, 24(3), 184-188. Retrieved November 20, 2012, from CINAHL database. Medline Plus. (2012). Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster, Inc. Retrieved November 20, 2012, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/medlineplus/. Simona, R. (2012). A pediatric peripheral intravenous infiltration assessment tool. Journal Of Infusion Nursing, 35(4), 243-248. Retrieved November 20, 2012, from CINAHL database. Taylor, C., Lillis, C., LeMone, P., & Lynn, P. (2011). Fundamentals of Nursing: The Art and Cience of Nursing Care (7th ed). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer/ Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins.