Paper - What is DBR?

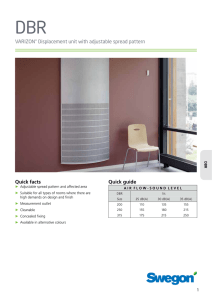

advertisement

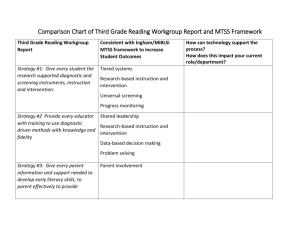

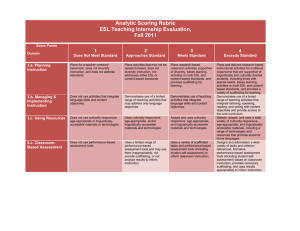

UGA Design Based Research Conference Proposal Putting the Design Back in Design Based Research: Problem Seeking and Scaling Insights from Mobile Learning Dr. Brenda Bannan – Associate Professor, George Mason University (bbannan@gmu.edu) Dr. John Cook – Professor The University of the West of England (johnnigelcook@gmail.com) Applicable Incubator Forum Themes: Innovative approaches to DBR methods and analysis Validating instructional theory and principles through design experiments Vexation How do we optimally incorporate design process and scaling into design research to generate/validate theory and principles? This vexation continues to provoke our thinking/action across multiple DBR projects. This recurring issue lies at the crux of the intersection of inductive creative process and deductive research efforts and the interplay of both to inform learning, design and practice. Several projects will be highlighted in this presentation including primarily a current European Commission funded mobile learning design research project addressing workplace learning, as well as mobile augmented reality user research project and an inquiry-based geosciences learning project. Venture To address how to integrate design processes and scaling to generate theory and principles for designs and learning, we need to first examine a few current models/frameworks of design process and design research. After reviewing these models/frameworks, we speculate on the extension of these to address the difficult issue of incorporating interdisciplinary perspectives on design process, generating theory/design principles from the wicked process of design and the complexity of defining, orchestrating, implementing and scaling outcomes of DBR. To begin, we address one framework that evolved from the first author’s work in design research. The Integrative Learning Design Framework (ILDF) has the general intent of generating research-based insights about informal or formal teaching, learning and/or training situations as well as applied solutions that provide and inform practical understanding and applicability to real-world design projects. The ILDF is a design-based research model that incorporates design process efficiencies from multiple disciplines such as instructional design, object oriented software development, product development, and diffusion of innovations research. |It aims to provide the opportunities to leverage the design process as a vehicle for analyzing, codifying and documenting what is learned when the designed artifact is enacted and in the context of the design process. The progressive yield from iterative and connected research and design cycles are often lost because it is not always carefully documented (Bannan-Ritland, 2009). It is expected that the design process for creating mobile learning (content and interactions) will offer several new opportunities to generate best practices and guidelines for both co-design process discussed below and design research. This framework consists of four phases (see Figure 1 below), and aims to solve the problem often encountered in traditional research of not capturing the research-based knowledge and important factors relating to learning context, culture, and technology within the design process (Bannan-Ritland, 2009). The ILDF requires that researchers contemplate the entire design-based research processes by phase in order to realize the scope of the research effort, from initial conceptualization to diffusion and adoption embedding theories of learning into designed artifacts (Bannan-Ritland, 2009). The four phases of Informed Exploration, Enactment, Local Evaluation and Broad Evaluation presented in the ILDF provide a process model for conducting more rigorous, design-based research iterative cycles, resulting in more comprehensive qualitative and quantitative research efforts than what formative evaluations alone can provide. The interconnected design research cycles can generate new knowledge about design principles, but also it can provide additional information on deeper aspects of learning, cognition, expert and novice perspectives, as well as stakeholder positions and organizational policy decisions (Bannan-Ritland, 2009). The co-design process offers some additional and varied insights into DBR frameworks/models such as ILDF presenting a different emphasis interestingly referred to as “research-based design” rather than “design-based research.” This design process, also called co-design, was conceived and articulated by the Aalto University’s Learning Environments research group and has been developed internally over a decade of international research and development projects. In research-based design, the artefacts generated from the design process, which can include tools, are considered to be outcomes. In this process, the researcher is the facilitator that guides way to the outcomes. We can distinguish certain phases in the process, although, one of the most important aspects is that many activities are going on in parallel, and often in the iterative cycles; indeed one may be required to go back to previous cycles. The process also claims to allow different strands of design that are in different phases to go forward within the same project. This is important to notice because one of the advantages is that even though there are strands that are on different phases these can potentially still feed knowledge into each other due to the iterative nature of the cycles. The main phases that can be distinguished are (see Figure 2): Contextual inquiry, Participatory design, Product design and Software prototype as hypothesis phase. The research-based design process (co-design) starts with an exploration of the socio-cultural context of design area. In the co-design, artifacts, tools, and services are used as a means of providing boundary and shared objects (mediated artifacts) to communicate between different participants during design activities. The idea is to avoid misunderstandings which can easily arises from using expert jargon, especially if no concrete artifacts are used. However, unlike in design-based research, in research-based design, the design is an essential outcome of the design activities. The research-based design process is iterative and takes place in close collaboration with various people concerned with the design. Outcomes of this phase in the Learning Layers project, that second author is currently engaged in, has been for example the following: user stories, interview descriptions, scaffolding concepts and design artifacts. In the Learning Layers the participatory design phase involves the most intense input from end users, partners and end-user representatives. The focus is on the actual and practical design, namely, trying to pinpoint most interesting and worthwhile tools for scaffolding informal learning and creating these ideas into gradually increasingly concrete prototypes. The involved people create sketches, storyboards, mock-ups, wireframe, videos of acted processes. Outcomes of this phase in the Learning Layers project has been for example the following: board games, context cards, design ideas, storyboards, refined user stories, contextual factors, more refined scaffolding “models”. The product design phase which we have not reached yet in the Learning Layers project attempts to define use cases, more specific technical requirements and works to define basic interactions through the mediating artifacts such as prototypes from low fidelity to high fidelity. Outcomes involve Scaffolding “models” that can be used for the semantic layer of technology, concrete points of integration start to appear, functional prototypes. In the last phase, the production of software as hypothesis, the agile software development is in full form. Modular designs of the software is the focus in this phase. These can be tested in actual use by the end users in the field. These prototypes are like hypotheses. In practice this means that the modular functional tools provide potential solutions to the design challenges defined earlier in the process. The third diagram (Figure 3) under the visuals heading below represents a model for Design Research that extends existing approaches so that they take account of design creativity and scaling of design (the later in terms of numbers of users and the complexity of research projects). The model draws on some of Rogers’ (1983) notion of diffusion of innovation, particularly his ‘model of stages in the innovation-decision process’ (p 163) and the ‘five stages in the innovation process in the organization’ (p. 392). However, the experience of the authors and other research have led to the model, we particularly draw on experiences of Learning Layers Project for scaling in workplace learning and the Layers Design Team PANDORA which is exploring collaborative support for maturing local living documents and the building personal and professional learning networks using mobile and social media (Cook, 2013). The focus of this paper will provide an innovative perspective on the potential of collaborative technologies that are embedded in workplaces and practices, and which contribute to and help to scale learning on the individual, group or organizational levels; specifically we will attempt to expound on DBR methodological work (Design and Seeking model) and original technology design examples that shed light on the identified vexations above. Visuals Figure 1: The Integrative Learning Design Framework (ILDF) Figure 2: The Co-design approach of Aalto University Figure 3: Design Seeking and Scaling Diagram Conclusion This proposed paper is meant to stir thinking about DBR in the context of educational design, particularly mobile learning design, design process and scaling of DBR products. We look forward to a potentially rich and productive exchange about these issues and projects that have prompted DBR work and may potentially extend our current models. References: Bannan-Ritland, B. (2009). The integrative learning design framework: An illustrated example from the domain of instructional technology. In T. Plomp & N. Nieveen (Eds.), An Introduction to Educational Design Research. Enschede, Netherlands; SLO Netherlands Institute for Curriculum Development. Cook J. and Pachler N. (2012). Online people tagging: Social (mobile) network(ing) services and work-based learning. British Journal of Educational Technology Vol 43 No 5 2012 711–725. Rogers, E. M. (1983). Diffusion of Innovations. The Free Press: New York.