Phoebe Dent Weil - Arts & Sciences Pages

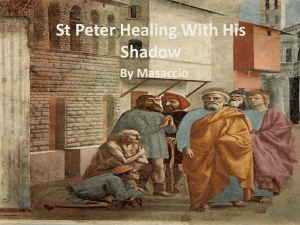

advertisement

THE HIDDEN LIFE OF PAINTINGS: ROCKS, ROOTS, BEETLES & ALCHEMY PHOEBE DENT WEIL www.northernlightstudio.com 2 DOING TECHNICAL ART HISTORY Cambridge MS: fresco painters at work, 13th c. Exploration of the "hidden life of paintings"--of all that goes in to the making of works of art--its materials and their subsequent changes-begins with Technical Art History. Art History is concerned primarily with the visible aspects of works of art while Technical Art History explores both the visible and invisible now made possible by highly sophisticated scientific methods of documentation and analysis. "Technical Art History" has therefore come to refer to the study of works of art in a larger framework. Beyond the study of historical context, meaning, significance, style, and artistic intent there is a need to take in to account the "hidden life" of works of art which is to be found in its physical body that carries the artistic message and on which that message depends. Further, the word "technical" derived from the Greek "tekné" meaning "to make" refers to the study of works of art not only by scientific techniques but also to the study of how works of art are made and to experiencing the making aspect through doing reconstructions or "informed copies." This "hidden life" has been until recently the almost exclusive and privileged domain of Art Conservators whose primary concern is with the care and preservation of the physical body of art works and whose training must encompass both thorough art historical understanding of the works they must preserve--problems of meaning, 3 value and significance--but also an understanding of the materials used by the artist, their complex behavior, the artist's working methods and the various chemical and physical processes of deterioration and change that occur with the passage of time. The modern field of Art Conservation was ushered in by the experience of two World Wars and by heightened awareness of the great fragility and vulnerability of works of art that are the cornerstones of our civilization. Any of you who are familiar with the book, The Monuments Men, and the subsequent movie will have some idea of the impact of the trauma of war and its impact on the development of the modern field of Art Conservation. For many years, as Art Conservation developed as a profession in the 20th century with graduate training programs for Conservators and with increasingly sophisticated methods of scientific study being used to study and to document the materials of works of art, the previously "hidden" aspects of artworks have gradually become more and more revealed. At first, many museums hesitated to reveal the "inside information" that scientific studies such as those made by x-radiography, infra-red photography, and chemical analysis revealed about the true state of a painting's condition which may have been, in some cases, an embarrassment. Transparency about condition has gradually won over secrecy as museums have discovered that information about condition and fabrication techniques is of great interest to the general public and it is now not unusual to see such information published in museum catalogues and small displays of materials and tools displayed as part of exhibitions. In the post-War era the educational value of doing reconstructions was recognized and taught at Harvard's Fogg Museum as essential training for Art Historians, Conservators. This course was discontinued for several decades but has been recently revived. Such courses are now being offered to undergraduates at other colleges and universities to augment the traditional Art History curriculum. Teaching of these courses has typically stimulated fruitful cross-disciplinary collaboration between the sciences and humanities. 4 INTRODUCTION TO PAINTING MATERIALS AND METHODS The aesthetic experience is...inherently connected with the experience of making." --John Dewey "If you want to know who I am, try to make what I make." -Gail Mazur _______________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION-DEMONSTRATIONS: 1. Making Iron gall ink: Oak galls + ferrous sulfate soln. 2. Pigments: inorganic & organic /natural & synthetic a. Inorganic, natural: malachite and azurite b. Organic, synthetic: Lake pigments: cochineal red and buckthorn yellow 3. Pigment properties: index of refraction, particle size 4. Early chemistry: verdigris--copper over vinegar; (Egyptian blue, Lead white, vermilion) I: DRAWING MATERIALS, ARTIST CONTRAPTIONS and THE EDUCATION OF THE PAINTER 1. Silver point 2. Graphite 3. Iron gall ink: quill, reed, brush 3. Natural chalk, red, black and white 4. The Camera Obscura 5. Education of the artist: "how to" manuals II. PAINTING TRANSITIONS: FROM EGG TO GLUE TO OIL & FROM WOOD TO CANVAS III. PAINTING TRANSITIONS IN OIL: FROM HAND GROUND TO TUBE PAINTS 5 REMBRANDT'S PIGMENTS: 17th c. Dutch LEAD WHITE: (It. Biacca; flake white, Cremnitz white) TOXIC: Poisonous if inhaled as dust or ingested. Basic lead carbonate [2PbCO3 . Pb (OH)2]—Made by exposing lead to vinegar vapor and subsequently to CO2 produced by decomposing manure or tanbark, as described in the ancient literature by Theophrastus, Pliny and Vitruvius. It is also found in nature as the mineral cerrussite. It was manufactured in the 17th c. by the ‘Dutch’ or ‘stack’ process. It can be used for thick impasto as it enhances the drying of linseed oil without distortions. Lead white is highly absorbent to X-rays. Cremnitz white is prepared by the action of carbon dioxide on litharge (PbO), and is considered whiter, denser, and more crystalline than ordinary Dutch-process white lead. When heated at moderate temperature it turns bright yellow because of the formation of massicot ; higher temperatures melt the massicot and changes it to litharge and even further heating oxides it to red lead (minium). Pure lead white was known as schulpwit, or flake white; a cheaper grade to which chalk was added was known as ceruse or loodwit and was used for grounds and for underpaint layers. Rembrandt used lead white in flesh tones, white cuffs and collars and in pastose highlights. CHALK: (calcium carbonate, whiting) [CaCO3]--occurs naturally. Largely composed of remains of minute sea organisms. Chalk was used in the Netherlands combined with animal skin glue as the primary constituent of grounds for panel painting, whereas gesso (calcium sulfate) was used in Italy. Chalk is fairly transparent when mixed with linseed oil. Rembrandt used chalk to add body and translucency to other pigments without changing color. VERMILION (cinnabar, It. Cinabro): [HgS] TOXIC- poisonous if inhaled as dust or ingested:—Mercuric sulfide—Found naturally as the mineral cinnabar which is the principal ore of the metal mercury. Pliny referred to it as minium, which later came to refer to red lead. It comes in various shades of red according to its method of preparation. Vermilion is one of the heaviest pigments, having excellent body and hiding power. It goes black after prolonged exposure to strong light. Strictly speaking, “cinnabar” should refer to the natural product, while “vermilion” should apply exclusively to the artificial product (heating black mercuric sulfide). Dutch vermilion, produced by direct combination of mercury and sulfur with heat followed by sublimation, was highly developed in the time of Rembrandt. Rembrandt typically preferred to use a bright red ocher heightened by the addition of red lake rather than vermilion which he used only occasionally. THE LAKE PIGMENTS—transparent glazing pigments produced from textile dyes fixed to a precipitate formed with alum and potash or to a chalk substrate. They were typically used in oil painting to produce effects of richness and depth over opaque underlayers, though rarely used for this purpose by Rembrandt who typically mixes lakes directly with other pigments to enrich their color. 6 RED LAKES: MADDER LAKE (It. Lacca, alizarin crimson): --derived from the name of the insect “coccus lacca”. Madder lake is a natural dyestuff from the root of the madder plant (rubia tinctorium)---formerly cultivated extensively in Europe and Asia Minor. The coloring matter is extracted from the ground root by fermentation and hydrolysis with dilute sulfuric acid. Madder lake and rose madder for artists’ pigments are prepared from the madder extract by adding alum and precipitating with an alkali. Synthetic manufacture begins in 1868. Madder lake is a poor dryer in linseed oil. CARMINE: COCHINEAL CARMINE (grana): --natural organic dyestuff made from the dried bodies of the female insect, coccus cacti, which lives on various cactus plants in Mexico and in Central and South America. First brought to Europe shortly after the discovery of those countries, about 1523. The coloring principle of cochineal extract is carminic acid which gives a scarlet red solution with water and alcohol and a violet solution with sodium hydroxide. The cochineal lakes are not permanent to light. In oil, however, they are fairly stable. Cochineal lake is a poor dryer. KERMES CARMINE (granum, vermiculus, coccus, <krim Persian for worm): --from a similar wingless scale insect found in different areas of Europe and theOrient. The host plants are scarlet oak, roots of the perennial knawel and strawberries as well as broad beans. Kermes contains only about 1/10 the amount of coloring matter as cochineal. Carmine nacarat is a very pure form of carmine. Lac is a colorant related to cochineal and kermes, produced by the lac insect in India and South East Asia. YELLOW LAKES: BUCKTHORN (schietgeel, giallo santo, Dutch pinke, stil de grain): --made from unripe Buckthorn berries, of which the color is extracted with potash and fixed onto a substrate of aluminum hydrate. Yellow lake in oil is perfectly transparent since the refractive indices of aluminum hydrate and oil are very close to each other. Unfortunately the yellow color in schietgeel, rhamnetin, is not lightfast, causing the yellow glaze to fade, and if over a blue underpaint to produce green, the blueish color underneath will become dominant. The name derives from verschietgeel which means “disappearing yellow”. When precipitated onto a chalk substrate, the pigment was known as a pink or pinke . Rembrandt typically used buckthorn yellow mixed with other pigments thereby avoiding the problem of fading. Lake made from the purplish ripe buckthorn berries produces a lake pigment known as sap green. Buckthorn is a poor dryer. WELD: --natural yellow dyestuff, obtained as a liquid or as a dry extract of the herbaceous plant, Dyer’s Rocket (Reseda luteola) formerly cultivated in central Europe. Weld is a poor dryer. 7 LEAD-TIN YELLOW (massicot, It. Giallorino or giallolino): [Pb2SnO4] TOXICPoisonous if inhaled or ingested: --a lemon-yellow to slightly orange-pink manufactured pigment, used mainly during the 15th to 17th century. It was apparently developed in connection with ceramic glazes and opacifiers for glass. Like lead white it is a dense and opaque pigment, dries well in linseed oil and can be used to produce high impasto highlights. EARTH PIGMENTS— OCHERS, SIENNAS, & UMBERS—all from naturally occurring sources and all containing natural ferric oxide (Fe2O3)—The earth colors are very stable in all painting media and do not interact with other more chemically sensitive pigments. Their stability, range of color and range of translucency to opacity suited Rembrandt’s purposes well and therefore tend to predominate in most of his paintings. Ochers, the most opaque of the earth colors, are fairly pure hydrated (yellow) or anhydrous ferric oxide (red), with colors ranging from yellow, orange, brown or red. Siennas contain greater proportions of mineral impurities in addition to the ferric oxide, especially alumina and silica that makes them more transparent. Siennas can be used raw or roasted (burnt sienna) to produce a warmer shade. Umbers contain in addition to iron oxide, some black manganese dioxide that has a siccative effect on linseed oil. Therefore they are useful additions to ground layers to promote faster drying. Umbers can be used raw, or gently heated to produce burnt umber that has a warmer tone. CASSEL EARTH (Cologne earth, Vandyke brown)—not strictly speaking an earth pigment but rather an organic pigment containing some inorganic minerals originating from peat or decayed wood deposits. It is a transparent brown often used by Rembrandt for his initial monochromatic sketching-in of a composition and for deep brown background glazes. Cassel earth is a very poor dryer, hence Rembrandt always mixed it with other earth pigments to avoid this defect. BLUES: SMALT (It. Smalto): --a blue potash glass containing cobalt oxide as coloring ingredient, popular because of its low cost. Smalt manufacture became a specialty of the Dutch and Flemish in the 17th century. If ground too fine, it loses its color, therefore the particles of smalt found in paint layers are usually quite large. Smalt discolors in oil, as the cobalt migrates out of the glass into the oil, leaving behind an unsightly olive green color. It eventually deteriorates to a mottled gray because of reaction of the alkali content of the smalt with the oil medium. The admixture of lead white prevents discoloration to a degree. Smalt was used in the Delft ceramic industry as the blue color in Delft tiles. Smalt is a very good dryer and was used by Rembrandt for this purpose and also to give bulk to thick glazes containing lake pigments which are poor dryers .AZURITE (It. Bice): --basic copper carbonate [2CuCo3.Cu (OH)2]. It occurs in mines of copper and silver, frequently together with malachite, and has a somewhat greenish appearance. It is ground coarsely because fine grinding causes it to become pale and weak in tinting strength. Traditionally it was most used in a tempera medium because in oil it darkens and becomes muddy. Verditer, a 8 synthetic azurite was available in the 17th century and has been found in some of Rembrandt’s paintings. Azurite appears more frequently in Rembrandt’s early work. In the later pictures Rembrandt invariably used smalt for blues. Azurite is a good dryer because it contains copper that has a siccative effect on linseed oil. Rembrandt therefore often added azurite to pigments that were poor dryers. BLACKS: BONE BLACK: (and ivory black) –a deep warm black made of ivory or bone burned in closed retorts, consisting of carbon and calcium phosphate.[C.Ca3(PO4) 2]. Usually bones from glue stock, boiled to remove fat and glue, are used. Ivory black is considered the deepest black of all and was used extensively by Rembrandt in the sketchy under-layers of his paintings and for the deep black of the costumes worn by his sitters. Bone black is a poor dryer. CHARCOAL BLACK : (vine black) –made from the residue of dry distillation of wood by heating the wood in closed chambers or kilns. It has a bluish tone when mixed with lead white. Under the microscope it is easy to distinguish the plant fibers. Rembrandt used charcoal black primarily as a gray tinting pigment in the upper ground layer on his canvas paintings which occasionally can be visible as the cool half tones in flesh areas. __________________________________ OTHER HISTORIC PIGMENTS OF INTEREST LAPIS LAZULI- -is a precious stone of a deep blue color with white veins of quartz and golden glittering flecks of pyrite. The blue mineral is a complex sodiumaluminum-silicate containing sulfur. The blue color is due to the sulfur ion. Cennino Cennini gives a method for purifying the mineral for use as a pigment. To obtain a pure blue pigment, the stone is crushed and ground and then separated from the impurities making use of the different affinity to fat and water of the various components. Quartz and pyrite are slightly less hydrophilic than the blue ultramarine. By mixing the powder into a paste of wax and oil and subsequently slowly releasing it into lukewarm water, the more hydrophilic ultramarine comes out first, quartz and pyrite stay behind. The process is very time-consuming: the stone, to start with, is expensive, so the resulting blue pigment is very expensive indeed. It is therefore used with great care. One way to economize on ultramarine was to put it over a dark under-layer or over smalt. It was usually tempered with walnut or poppy oil, neither of which yellowed as much as linseed oil, and thinned with turpentine, or oil of spike to make a lean paint. Synthetic manufacture begins around 1830. It is permanent to light and stable in fresco. Since the refractive index of ultramarine is so low, it serves better and is far brighter in tempera than in oil. It is discolored in an oil or a varnish film as they yellow with age producing a greenish appearance. Ceneri d'azzurro, or "ultramarine ashes", a residue of ultramarine after the purest particles have been extracted. EGYPTIAN BLUE (calcium copper silicate)-the first synthetic pigment--very stableused from early dynasties in Egypt until end of Roman period 9 GREEN EARTH (terra verde): an earth occurring naturally near Verona, also in Tyrolia and in Bohemia-The coloring ingredient is iron present in the minerals glauconite and celadonite. They are compatible with all binding media, but they have very low hiding power in oil. LEAD-TIN-ANTIMONY YELLOW: [ternary oxide of lead, tin and antimony] TOXICunlike Naples yellow which is pure lead antimonate- This pigment, warmer hued than lead-tin yellow, was identified as that used by Orazio Gentileschi for the yellow dress of the Lute Player and in St. Cecilia and an Angel in the National Gallery in Washington. It appears to be restricted in use to Italian painting and specifically to paintings produced in Rome. (see article by Ashok Roy and Barbara H. Berrie, "A New Lead-Based Yellow ...." WELD: -natural yellow dyestuff, obtained as a liquid or as a dry extract of the herbaceous plant, Dyer's Rocket (Reseda luteola) formerly cultivated in central Europe. Buckthorn (giallo santo) was another source of yellow dye, also fugitive. ORPIMENT (Auripigmentum): [As2S3] TOXIC.-yellow sulfide of arsenic, occurs naturally, also made artificially. Bright yellow, sometimes almost orange color, with a crystalline, glittering appearance. Used as a fly killer mixed with honey (Symonds MS). Realgar, the natural orange-red sulphide of arsenic [As2S2] is closely related chemically and associated in nature with orpiment. INDIAN YELLOW: -a yellow organic extract formerly prepared in India from the urine of cows that were fed on the leaves of the mango-now made synthetically. VERDIGRIS (It. Verde Tame) (Vert de Grece): -basic copper acetate-Known in ancient times, its preparation was described by Theophrastus and Pliny. Prepared by exposing sheets of copper to vinegar vapor. The resulting copper acetate is scraped off and the copper sheet placed back over the vinegar. Verdigris was used in oil, even though there are many warnings against using it in the treatises from the 16th c. onward, as it turns dark brown. It is the most reactive and unstable of the copper pigments. COPPER RESINATE: -a transparent, amorphous green of copper salts of resin acids formed when verdigris-basic or neutral copper acetate-reacts with a varnish. It is made by heating and dissolving copper acetate in colophony (rosin) and Venice turpentine resins. Balsam or other similar resins may be used as well. It produces a transparent green glaze. ASPHALTUM (It. Spalto) or BITUMEN also SPALTE, ASPALATHUM: "-a brownish black, native mixture of hydrocarbons with oxygen, sulfur, and nitrogen, and often occurs as an amorphous, solid or semi-solid liquid in regions of natural oil deposits." (Gettens and Stout, p.94) Prepared by heating in a drying oil, bitumen tends to 10 absorb the oil to produce a rich, transparent brown that never completely dries, and ultimately causes serious cracking in the paint layers. Identified by Ann Massing in a painting by Orazio G.(see: A. Massing, "Orazio Gentileschi's Joseph and Potiphar's Wife) CAPUT MORTUUM is the name for stronger burnt dark purple varieties of iron oxide. GENERAL WEB RESOURCE ON PIGMENTS: http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/ GLOSSARY OF TERMS PRINCIPAL RESOURCE: Gettens and Stout, Painting Materials: A Short Encyclopedia DRAWING PRINCIPAL RESOURCE: J. Watrous, The Craft of Old Master Drawings, Madison, WI, 1957. Paper: In addition to white or off-white, two popular types of toned paper: turchina : pale blue, made with indigo dye, which seems to have originated in Venice in the latter 15th c. and used throughout Italy by the 17th c; beretta: greenish-gray. The paper could also be toned with washes, e.g. with bistre or tinted gesso thinly applied. Chalk (It. lapis, lapis negro, lapis rosso etc.): black, red, white, trimmed with a knife and held in a tocha lapis (Fr. porte-crayon) (chalk holder); also charcoal, graphite, and lead white in watercolor form for highlights. Pen: quill Tocha lapis: chalk holder for ease in manipulating the piece of natural chalk without having to hold it with your fingers Ink: Lamp black plus gum water; also iron gall ink made from oak galls soaked in water for several days and then adding some ferrous sulfate to make a deep violet, browns with age and occasionally eats away the paper if acid content is too high; bistre made from resinous wood soot. (See photos of iron gall ink being made in our workshop. http://www.knaw.nl/ecpa/ink/index.html is a website about iron gall ink) 11 PAINTING--16th-17th c.: Support: Canvas: The use of linen as a support was introduced in the 15th century by Northern Artists (Bouts, Brueghel) and adopted by artists in Northern Italy (Mantegna) who used it with distemper (glue medium). The advantage of linen for portability, compared with wood panel typical for egg tempera and early oil painting, led to its widespread adoption and use for oil painting which then took precedence over the more delicate and fragile distemper. Linen was attached by tacks to a board for distemper with a felt liner to separate it from the wood. For transport it could simply be removed from the board and rolled up. For oil painting canvas was typically attached to a strainer using tacks. In Holland canvas was often stretched with strings to a strainer like a ship's sail so that it could be tightened as needed by simply pulling the strings rather than pulling out the tacks to restretch. The expandable stretcher was invented shortly prior to 1775. Early small distemper paintings were called tüchlein and were on a linen of very fine weave. In Rome, 17th c., linen for painting was typically plain (tabby) weave with density of 7 to 8 threads per cm2 i.e. fairly coarse weave, giving a craquelure pattern of small squares. For large paintings canvases were typically pieced and sewn together. Wood panel: prepared with a layer of rabbit skin glue and one or more layers of gesso. For oil painting, to counteract the excessive absorbency of the gesso ground, the panel was covered with an imprimatura or priming of ogliaccio (nasty or dirty oil) probably based on sediment from cleaning the brushes and palette, to reduce but not totally remove the absorbency of the gesso and to provide a toned ground, even or streaky. Copper: prepared with one or more very thin layers of lead white or lead white plus small amounts of red or yellow ochre and carbon black in linseed oil [see: Isabel Horovitz, "The Materials and Techniques of European Paintings on Copper 1575-1775" Canvas preparation: Glue size: applied hot or cold to isolate the oil-based ground from the canvas Ground:Applied with a priming knife. Preliminary layer to fill interstices of canvas weave and provide a smoother painting surface, of white gesso in Italy up to end of 16dt c. Colored grounds were used in the early 16th century in North Italy by e.g. Correggio, Dosso Dossi and Parmigianino. By 1600 colored grounds were common practice and available commercially throughout Italy and in the North, typically a double ground, the first (lowest) a red-brown, composed of any or all 12 of the following: leadwhite, red and/or yellow ochre, umber, chalk, or gesso, and carbon black; the second, referred to as the imprimatura, applied by the artist in the studio, was typically a cool gray, composed of lead-white and carbon black. The second layer is occasionally omitted, typical for Caravaggio, and often in Artemisia. There were a number of alternatives such as the use of a white preliminary ground followed by a thin, streaky warm-toned imprimatura (Rubens), or a white preliminary ground followed by an even-toned pinkish or buff-colored imprimatura (Vermeer). Paint layers: Underdrawing/ undermodeling: Note on use of sgraffitto outlines: Dead coloring, (It. sbozzo): blocking in the main areas of color. Dead coloring could be different from and have a particular desired effect on the surface color. Painting / glazing (velare, velatura) / wet-on-wet / oiling out: Varnish: -"amber varnish"(probably copal and colophony) used selectively and not overall, in Orazio's paintings for "oiling out" where medium has sunk in (prosciugare) and to produce smooth effects in paint applied subsequently. Both drying oils and resins were used. Not much physical evidence remains because of subsequent cleaning to remove discolored coatings. Various opinions regarding the use of varnish can be found in the 17th c.(see: Felibien; Marco Boschini, La Carta del NavegarPittoresco, Venice 1660; Baldinucci, "11 Lustrato"; De Mayerne) etc. Brush (It. penello, old English pencill or pensill): -two types: bristle from hogs hair (setola) and those made from finer hair, like the polecat (puzzola), minever (vaio) and badger (tasso) [see: Rosamond Harley, "Artists' Brushes-Historical Evidence from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century"] Klad pot: a small box that usually held some linseed oil where un-used paint could be discarded and then re-used, for example, in making a colored imprimatura Mahlstick (or maulstick): stick, about a yard long, with padded end used to support and steady the hand while painting. Palette (It.tavoletta): -fine-grained wood (walnut or boxwood) flat surface that could be held conveniently near to the surface being painted. Palettes typically have a thumb hole for a stable grip in the artist's (usually left) hand. The artist can arrange small blobs of paint on the palette and keep it conveniently close to the surface that is baing painted using a brush held in the free (typically right) hand. Early (medieval) palettes were quite small as pigments were costly and 13 had to be freshly ground each day in small amounts. Palettes became larger as oil paint was introduced. Pigments ground in linseed oil could be deposited in mussel shells and submerged under water to preserve it for several days. With the arrival of commercially prepared oil paint in tubes in the 19th century and its use, for example, by Monet on large canvases, palettes of fairly large size were employed. Easel (It. palcho)--: support for painting for work in progress Pincelier: container for solvent for cleaning brushes Color grinding equipment: grinding slab (preferably a hard non-porous stone like porphyry) and grinding stone or muller MEDIUMS: DRYING OILS AND RESINS Linseed oil: from the flax plant. Stand oil is linseed oil thickened by heating in the absence of oxygen. Viscosity can be increased by simply heating the oil to produce "burnt plate oil" used in inks and to produce a more viscous paint. See article "Rembrandt and Burnt Plate Oil" on website <www.northernlightstudio.com> Walnut oil: Poppy seed oil: "Amber varnish from Venice of the kind used for lutes":-mentioned by de Mayerne as used by Orazio (and Artemisia) G., "especially for the flesh areas so that the whites can be applied more easily and give a sweeter effect. In this way he works at his leisure without waiting for the colors to dry completely." Orazio's "amber varnish" was probably a combination of colophony and copal resins recently identified in the Getty Lot (see: Mark Leonard, et.al., "'Amber varnish' and Orazio Gentileschi's 'Lot and his daughters"') Various resins: Sandarac, mastic, damar, colophony (pece Greca), Venice turpentine, etc ADDITONAL TERMS cangiante: -literally "changing"--Italian term for shot fabrics-i.e. fabrics with warp and weft in different colors so that the color changes depending on angle and direction of light-In painting, drapery has different hues in the light and dark areas, and shadows are without black, but rather a pure color 14 contorni: outline, extolled by Pliny, Alberti, Annenini and theoreticians through mid-17th c. as a great challenge in disegno. The importance of contorno over ombra (shadow) was an important tenet of the classicists, beginning with the Carracci, and was used to demonstrate the "erring ways" of Caravaggio. METHODS OF COPYING, ENLARGING AND TRANSFERRING DESIGNS calco, calcare, ricalcare, incisione indiretta: stylus tracing or incision. Camera obscura: a darkened space, box or room, into which an image from outside is produced by light entering through a small hole or lens. The phenomenon was known in ancient times and in 17h century Holland lenses were employed to produce very sophisticated cameras. The painter Vermeer most certainly used a camera obscura in some way to produce his paintings. Just how he used it has been the subject of much recent speculation. Caravaggio is also thought to have used some form of camera obscura. graticola: -device made with strings stretched on a rectangular frame to form a square grid The strings could be chalked and snapped against a wall, canvas or other surface to transfer the grid pattern. A smaller scale drawing could then be squared off with a ruler and copied with reasonable accuracy to the surface squared off with the graticola. lucidi: tracing paper made by applying oil, e.g. walnut oil to paper to make it translucent According to the Volpato MS., the design could thus be traced in charcoal or colored chalk. If this design was to be transferred onto canvas, a piece of paper covered on the lower side with chalk was placed between this oiled paper and the canvas. 'By means of a bone needle or a metal stylus, the lines on the oiled paper were pressed onto the canvas, the chalk covered paper in berween leaving impressed all the marks which were indented with the needle. In order to transfer the design on to white paper, the middle paper was covered with charcoal, or with red or black chalk. (See: Beal, M., Symonds) spolvero: -technique of transferring a drawing to another surface, e.g. cartoon to canvas or wall. The drawing was perforated along the lines and applied to the intended surface. The punched lines were pounced with a small bag of charcoal dust producing a dotted line on the canvas or wall. 15 BIBLIOGRAPHY ON HISTORIC PIGMENTS with additional basic references on historic painting techniques, technical art history and reconstruction, useful websites *See: http://www.northernlightstudio.com Especially “Illustrated list and description of pigments found in 17th c. Painting” http://www.northernlightstudio.com/pig17.php And addidtional bibliographies : http://www.northernlightstudio.com/biblio17ital.php General Sources: Albus, Anita, The Art of Arts: Rediscovering Painting, tr. M. Robertson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf) 2000. Ball, Philip, Bright Earth: The Invention of Colour (London: Penguin) 2001. Bomford, David, Christopher Brown and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Rembrandt (London:National Gallery Publications) 1988. See especially, “Rembrandt’s Painting Materials and Methods”, pp. 21-26. Bomford, David, Jill Dunkerton, Dillian Gordon, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Italian Painting before 1400 (London: National Gallery Publications) 1989. Cennini, Cennino d'Andrea, The Craftsman's Handbook: "Il Libro dell'Arte", tr Daniel V. Thompson, Jr. (New York: Dover) 1933; 1960. Cennini, Cennino d’Andrea, Il Libro dell’Arte, a cura di Franco Brunello (Vicenza:Neri Pozza Editore) 1982. Chenciner, Robert, Madder Red: A history of luxury and trade, Caucasus World ser. (Richmond, Surrey, UK: Curzon Press) 2000. Clarke, Mark, The Art of All Colors (London:Archetype) 2001. Delamare, François, Blue Pigments: 5000 years of and Art Industry, (London:Archetype) 2012. Delamare, Francois and Bernard Guineau, Colors: The Story of Dyes and Pigments, Discoveries series (New York: Harry N. Abrams) 2000. Dunkerton, Jill, S. Foister, D. Gordon, N. Penny, Giotto to Durer: Early Renaissance Painting in the National Gallery, (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press) 1991. ______________________________________, Dürer to Veronese: Sixteenth-Century Painting in the National Gallery (New Haven and London: Yale University Press and National Gallery Publications Ltd.) 1999. (especially chapters 6-9) Eastaugh, Nicholas, V. Walsh, T, Chaplin, and Ruth Siddall, The Pigment Compendium: A Dictionary of Historical Pigments (Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford and Burlington, MA) 2004. 16 ___________, The Pigment Compendium: Optical Microscopy of Historical Pigments (Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford and Burlington, MA) 2004. Feller, Robert L. (vol.1), Ashok Roy (vol.2), and Elizabeth West Fitzhugh (vol. 3), eds. Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics, 3 vols., (vol. 1, Cambridge and Washington: Cambridge Univ. Press and National Gallery of Art) 1986; (vol. 2, Washington and New York: National Gallery of Art and Oxford University Press) 1993; (vol. 3, Washington and New York: National Gallery of Art and Oxford University Press) 1997. Finlay, Victoria, Color: A Natural History of the Palette (NY: Ballantine) 2003. Gettens, Rutherford J. and George L. Stout, Painting Materials: a Short Encyclopaedia (New York: Dover) 1942,1966 Harley, Rosamund, Artists’ Pigments c. 1600-1835: a study in English documentary sources, 2nd ed., (London: Butterworth Scientific) 1982. Hermens, Erma, ed. Looking Through Paintings: The Study of Painting Techniques and Materials in Support of Art Historical Research (London: Archetype) 1998. Kirby, Jo, Susie Nash and Joanna Cannon, Trade in Artists’ Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700 (London:Archetype) 2010. Languri, Georgiana M., Molecular studies of Asphalt, Mummy and Kassel earth pigments (Amsterdam:AMOLF) 2004. Phipps, Elena, Cochineal Red: The Art History of a Color (New York and New Haven: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press:) 2010. Spring, Marika, ed., Studying Old Master Paintings: Technology and Practice, The National Gallery Technical Bulletin 30th Anniversary Conference Postprints (London:Archetype) 2011. Thompson, Daniel V. The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting (New York: Dover} 1936; 1956. Thompson, Daniel V. The Practice of Tempera Painting (New York: Dover) 1956. Townsend, Joyce, T. Doherty, G. Heydenreich and J. Ridge, eds,. Preparation for Painting: The Artist’s Choice and its Consequences (London:Archetype) 2008. Wallert, Arie, E. Hermens, and Marja Peek, Historical Painting Techniques, Materials and Studio Practice, Symposium Preprints, Univ. of Leiden, 26-29 June 1995 (The Getty Conservation Institute (Lawrence, KS: Allen Press) 1995. 17 Additional basic resources on historical materials/techniques: treatises Leon Battista Alberti On Painting, tr. and ed. John R. Spencer. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966. Eastlake, Charles Locke, Methods and Materials of Painting of the Great Schools and Masters, 2 vols. (New York: Dover) 1847, 1960. Mayeme, Sir Theodore Turquet de, Pictoria, Sculptoria & quae subalternarum artium, (1620, with entries dating until 1646) British Library, BL Sloane MS 2052. 1. Ernst Berger, Quellen fur Maltechnik wahrend der Renaissance und deren Folgezeit (XVIXVII Jahrhundert) nebst dem de Mayeme MS. Beitrage zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Maltechnik, IV Folge, (pp.99-364) Munich, 1901, reprint 1973. 2. J .A. Van de Graaf, Het de Mayeme Manuscript als bron voor Schildertechniek van de Barok, Mijdrecht, 1958. 3. M. Faidutti and C. Versini, Le manuscript de Turquet de Mayeme, Lyon, n.d. [1968] 4. D.C. Fels, Jr., Lost Secrets of Flemish Painting, 2002. (includes English translation of De Mayeme MS B.M Sloane 205-on the Mayeme MS see: Trevor-Roper, Hugh, "Mayerne and His Manuscript" in Art and Patronage in the Caroline Courts, pp. 264-93, ed. David Howarth. (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press) 1993. Merrifield, Mary Philadelphia, Medieval and Renaissance Treatises on the Arts of Painting, Original Texts with English Translations, 2 vols. bound as one (New York: Dover) 1849, 1967, 1999. Pliny (Gaius Plinius Secundus or Pliny the Elder, 23-79 C.E.), Historia Naturalis (Natural History), 10 vols. Tr, D.E. Eichholz, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press) 1971. [-especially Bk.XXXV, or the following link: http://books.google.com/books?id=9zwZAAAAYAAJ&dq=Pliny+the+elder+on+pigments&so urce=gbs_navlinks_s Vasari, Giorgio, Vite (numerous editions available). Vasari, Giorgio, Vasari on Technique, L. Maclehouse and G. Baldwin Brown, tr. & ed. (New York: Dover) 1907, 1960. [Translation with notes of the Introduction to Vasari’s Vite 1550, rev 1556.] Veliz, Zahira, Artists’ Techniques in Golden Age Spain, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press) 1986. [contains the treatise Arte de la pintura, by Francisco Pacheco (Seville) 1649]. Da Vinci, Leonardo, Leonardo on Painting, Martin Kemp, ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press) 2001. 18 Distemper /Tüchlein Painting Dunkerton, Jill, S. Foister, D. Gordon, N. Penny, Giotto to Durer: Early Renaissance Painting in the National Gallery, (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press) 1991. “Glue Size Painting”, pp187-188; Figs. 207, 210, 212, 259, 164; and entries no. 32 pp. 296-97, Dieric Bouts “The Entombment”c. 1450-60; and no. 64. pp.372-375 Andrea Mantegna, “The Introduction of the Cult of Cybele at Rome 1505-6. Cennini , Cennino, op. cit. “Painting on Cloth”, pp. 103-4. Rothe, Andrea, “Mantegna’s Paitings in Distemper”; and Keith Christiansen, “Some Observations on Mantegna’s Painting Technique”, in Jane Martineau, ed., Andrea Mantegna (New York:Abrams)1992, pp. 80-88 and pp. 68-78. Devolder, Bart, “Two 15th Century Italian Paintings on Fine-Weave Supports and their Relationship to Netherlandish Canvas Painting”, Harvard University http://www.ischool.utexas.edu/~anagpic/pdfs/Devolder.pdf Villers, Caroline , review of The Beginnings of Netherlandish Canvas Painting 1400-1530, by Diane Wolfthal (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1989) in Burl Mag, Vol 133, No. 1057, Apr., 1991, pp. 258-259 [posted on Moodle site} For further exploration of the topic: Bomford, D. , A. Roy, and A. Smith, ‘The Techniques of Dieric Bouts: two paintings contrasted’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, X [1986], p.46; and A. Roy, ‘The techniqe of a “Tuchlein” by Quenten Massys’, ibid, XII [88), p.38. Dubois, H. & L. Klaassen, “Fragile Devotion: Two Late Fifteenth-Century Italian Tüchlein Examined” in Villers, C, ed., The Fabric of Images. European Paintings on Textile Supports in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, London, 2000. [SC Art/ND1840. F32 2000] Dubois, H, H. Khanjian, M. Schiling and A, Wallert, “A Late Fifteenth Century Italian Tüchlein”, Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung, 11:pp. 228-237. Dunkerton, J., “Mantegna’s Painting Techniques”, pp. 26-38 in Ames-Lewis, F & A. Bednarek, eds., Mantegna and 15th century court culture; lectures delivered in connection with the Andrea Mantegna exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1993. Leonard, F., F. Preusser, A. Rothe and M. Schilling, ‘Dieric Bouts’s Annunciation: Materials and Techniques, The Burlington Magazine CXXX (1988). Villers, Caroline, ed. , The Fabric of Images: European Paintings on Textile Supports in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, London, 2000 Wolfthal, Diane, The Beginnings of Netherlandish Canvas Painting 1400-1530 (Cambridge University Press) 1989. 19 Drawing Petherbridge, Deanna, The Primacy of Drawing: Histories and Theories of Practice. (New Haven: Yale University Press) 2010. Watrous, James, The Craft of Old Master Drawings (Madison, WI: Univ. of Wisconsin Press) 1957 Periodical: The National Gallery Technical Bulletin, vols. 1-30, London, UK. On Technical Art History and Reconstruction: Art Technological Source Research Study Group/ now Working Group of ICOM-CC http://www.icom-cc.org/21/working-groups/art-technological-source-research/ First Symposium: Art of the Past: Sources and Reconstructions (London:Archetype) 2005. Second Symposium: Art Technology: Sources and Methods (London:Archtype) 2008. Third Symposium: Sources and Serendipity: Testimonies of Artists’ Practice (London:Archetype) 2009. Bewer, Francesca, A Laboratory for Art: Harvard’s Fogg Museum and the Emergence of Conservation in America 1900-1950 (Harvard Art Museum and Yale University Press: Cambridge, MA and New Haven and London) 2010. Bomford, David, “Introduction”, Looking Through Paintings: the Study of Painting Techniques and Materials in Suppport of Art Historical Research, Erma Hermens, ed. London: Archetype, 1998, pp. 9-12. Carlyle, Leslie, “Beyond a Collection of Data: What We Can Learn from Documentary Sources on Artists’ Materials and Techniques”. Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice, Preprints, University of Leiden (Lawrence, KS: Allen Press Inc.) 1995, pp. 1-5. Dunkerton, Jill, and Rachel Billinge, Beyond the Naked Eye, (National Gallery Company: London) 2005. Haag, Sabine, Elke Oberthaler and Sabine Pénot, Vermeer, Die Malkunst (Vermeer, The Art of Painting) (Kunsthistorisches Museum:Vienna) 2010. Mohen, Jean-Pierre, Michel Menu, Bruno Mottin, Mona Lisa: Inside the Painting (Abrams: New York) 2006. Wrapson, Lucy, J. Rose, R. Miller, S. Buckllow, eds., In Artists' Footsteps: The Reconstruction of Pigments and Paintings (London:Archetype) 2012 20 Useful websites Ghent Altarpiece http://www.closertovaneyck.kikirpa.be Pigments http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/ http://www.northernlightstudio.com Especially “Illustrated list and description of pigments found in 17th c. Painting” http://www.northernlightstudio.com/pig17.php And http://www.northernlightstudio.com/biblio17ital.php Pigments and Refractive Index http://www.naturalpigments.com/education/article.asp?ArticleID=8 http://interactagram.com/physics/optics/refraction/ Art supplies: Kremer Pigments Inc. http://kremerpigments.com/ Iron gall ink: http://ink-corrosion.org/ Cutting quill pens from feathers: http://www.flick.com/~liralen/quills/quills.html 21 A 15th c. Northern Painter's Studio depicted by Stradanus where the Nova Reperta "new invention" of oil painting (here attributed to van Eyck) was practiced. Note that the support used here is the traditional wood panel. During the 16th century canvas stretched on a stretcher frame was gradually adopted as more practical, portable and less expensive. Clockwise from upper right: Delivery of newly prepared wood panels by workman entering the doorway; color grinders preparing paint with pigment and linseed oil using muller and slab; on the corner of the table, prepared paint placed in mussel shells; young apprentice copying eyes from a drawing textbook; older apprentice preparing a palette for the Master Painter who stands on a dais at work on a panel painting; advanced apprentice drawing from a classical bust; studio artist painting a portrait of a young lady with her nearby chaperone.