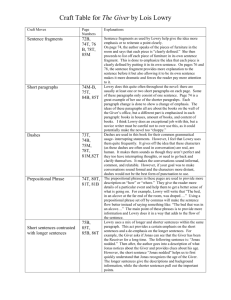

- University of Brighton Repository

advertisement

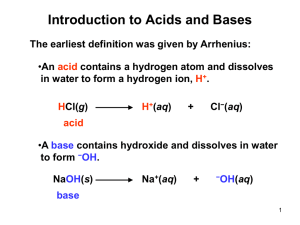

Aztecs and Zapotecs: The Day of the Dead and the Cosmic Phantoms of Malcolm Lowry Nigel H. Foxcroft, University of Brighton Introduction Inspired by a field-trip to Mexico in October – November 2010 for the Day of the Dead festival, this paper advances the thesis of my 2009 Malcolm Lowry Centenary International Conference paper on “Souls and Shamans: The Cosmopolitan Psychology of Malcolm Lowry” presented at UBC, Vancouver.1 Indeed, it gives further consideration to the cultural, psychological, and spiritual links between Lowry’s terrestrial, subterranean, cosmic, and aquatic worldviews. In assessing the interface between the material and spiritual domains of the Aztecs and the Oaxacan Zapotecs, this research examines the subconscious dimensions of the Mexican Day of the Dead festival witnessed by Malcolm Lowry. In so doing, it investigates various anthropological, cultural, and ethnographic influences. With their sources in pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican rituals, these stimuli are reflected in Lowry’s Under the Volcano (1947), Dark as the Grave Wherein My Friend is Laid (1968), La Mordida (1996), and The Forest Path to the Spring (1961). In analyzing his preoccupation with seeking atonement with the spirits of the dead, this paper aims to clarify Lowry’s recognition of the need to repent for the debts of the past and for the sins of mankind. It also attempts to penetrate his insight into Mexican cultural heritage by determining synergies in his worldview with the cosmic, shamanic, and animistic concepts of the universe, reflected in the divine consciousness of the Aztec and Zapotec civilizations. 2 From the Aztecs to the Zapotecs: A Psychogeographical Pursuit of the Spirits of Civilization Malcolm Lowry’s multifaceted, prismatic perception of his environment empowers him to encapsulate in his work an intriguing combination of terrestrial, temporal images, on the one hand, with celestial, spiritual dimensions, on the other. A reinterpretation of his vision of the world reveals various anthropological, psychogeographic, and psychoanalytical forces at work in his complex approach to what was to become Jacob Bronowski’s Ascent of Man.2 Furthermore, Lowry was intrigued by the ethnographic research promulgated in The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (1890-1915) by Sir James George Frazer (1854-1941), the Scottish anthropologist, folklorist, and classicist. Indeed, in his letters Lowry refers directly to this work – one which bears witness to the commemoration of the souls of the dead by what Frazer calls the “Miztecs of Mexico,” that is, the Mixtecs of Oaxaca and its environs.3 Entranced by the Mexican Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead celebration which he observed in November 1936 in Quauhnahuac – known today by its Hispanicized version of Cuernavaca – Lowry launches his multi-layered novel, Under the Volcano with a psychogeographical portrait of a city haunted by “the ghosts of ruined gamblers”.4 In what transforms into a psychologically profound vision of the world, perceived by an esoterically enigmatic, Cabbala-inspired state of consciousness, the reader is propelled into the inner depths of Lowry’s snapshot of civilization.5 However, it is a domain in which dwell strange combinations of numbers and bizarre coincidences of events which ostensibly determine the fate of mankind. Gradually, we are exposed to a mind-set which fosters beliefs akin to those held by both the Aztecs and, indeed, the Zapotecs who endeavoured to predict five 3 unlucky, unnamed days in their 365-day solar calendar. Stimulated by the impact of a particular American author and science critic, Lowry justifies his numeric beliefs by declaring, in his correspondence, that he has known “of no writer who has made the inexplicable seem more dramatic than Charles Fort” and proceeds to surmise that the cosmos is composed of certain immortal, mathematically-rooted patterns of existence.6 A prolific reader of world literature, Lowry was captivated by travel. Following in the footsteps of D. H. Lawrence in pursuit of adventure and cultural paradise, he was lured to Mexico twice – once in 1936-38 and again in 1945 – lodging in the cities of Cuernavaca and Oaxaca. Embarking upon a transcendental, supernatural quest for the Garden of Eden, he traced the cultural and historical origins of modern Mexico back to the Aztecs. Mesmerized by the cosmological legacy which they shared with the Zapotecs, he drew upon his lifelong interest in social, cultural, and linguistic anthropology as a way of comprehending the Spanish impact on Aztec civilization. Of special appeal were the consequences for his Mexican Garden of Eden of Hernán Cortés’s conquest and skilful subjugation of the Aztec Empire in 1519-21. In this respect, Lowry was enthralled by the ongoing dilemma facing the native Aztec and Zapotec civilizations: how to preserve their heritage while adjusting to a new politicocultural, Hispanic environment – a situation which led to a fusion of traditions in the Day of the Dead festival. The Cosmic Phantoms of the Mexican Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead In Aztec culture, death – as “a mirror of life” - is a symbolic celebration, necessitating an offering, or sacrifice to satisfy the gods and to nourish the souls of the deceased on their underworld journey 4 into the afterlife.7 It was deemed a great honour to be a sacrifice, for, as Jacques Soustelle has claimed, it was “believed that each human being was, by predestination, inserted into a divine order, ‘the grasp of the omnipotent machine’”.8 The Aztecs cherished the eternal Ferris wheel of life by practising the extraction of the pulsating heart of a ‘volunteer’, or, rather, a victim, with the intention of placating the gods and, hence, sustaining the universe. Associated with pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican rituals connecting the living with the fallen, the Day of the Dead festival derives its traditions too from shamanic and cosmic perspectives akin to those preserved by the modern-day, animist tribes of northern Mexico. In this respect, the Huichol (and the Yaqui) worship and communicate with numerous gods and spirits, giving thanks to Christian images, such as to the figurine of the Virgin of Guadalupe. In Under the Volcano this effigy appears as “the Consul’s longing” where it “was so great his soul was locked with the essence of the place”.9 In Dark as the Grave the revival of Sigbjørn’s faith is facilitated both by “the mediating influence of the dead” and by the statuette “of […] the Holy Virgin” which attracts the attention of Primrose and Sigbjørn “as a model ... dressed in bright print and carrying in one hand a lamp”.10 Moreover, it precipitates an acute “feeling of something Renaissance,” emphasizing the need for cultural and spiritual renewal.11 Rebirth for Lowry is closely connected to movements of the Pleiades (or Seven Sisters) star cluster which interfaces with the Day of the Dead and the 260-day ritual cycle of the Aztec and Zapotec calendar year. In this respect, Lowry informed the editor of the Vancouver Sun of his following discovery regarding the Pleiades: The Egyptians, the Aztecs, the Japanese all worshipped them. And the Festival of All Hallows, All 5 Saints Day, the Mexican Day of the Dead etc. are all associated with the culmination of the Pleiades. It is thought [...] that these universal memorial services commemorate a great cataclysm that occurred in ancient times.12 Furthermore, in Under the Volcano the Consul’s ex-wife, Yvonne shamed for eternity for her extra-marital affairs with Hugh and M. Jacques Laruelle – ironically imagines “herself voyaging straight up through the stars to the Pleiades,” as was the case with Merope, the faintest of the mythical Seven Sisters.13 Hence, it is the Pleiades – and the date of their first appearance in the sky - which link Aztec and Zapotec beliefs, as has been suggested by Clemente Vicente M.14 As a commemorative ritual, the Day of the Dead not only sets the scene but also provides a key to comprehending the true significance of Under the Volcano. Of pre-Hispanic, pagan-spiritual origin, this festival - deeply rooted as it is in ancient Aztec civilization – has been enriched by subsequent Spanish-Catholic influences. Held on 2 November each year, it comes after the commemoration of deceased children and infants on 1 November, known as the Day of the Innocents, or Little Angels. With its bright masks and skulls, vivid costumes, loud singing and dancing, and the display of orange marigolds and the favourite dishes and drinks of the deceased alongside their graves, this fete yearns to connect the living with the spirits of the dead. These evocative images are reproduced by Lowry in Under the Volcano which opens with Dr Vigil and M. Jacques Laruelle reminiscing about Yvonne and Geoffrey Firmin, now deceased, but immortalized in the events of the Day of the Dead. As with the Consul, the Aztecs too believed that, on this very day, the souls of the deceased – symbols of rebirth - journey back from the underworld to greet the land of the mortals. 6 Contacting the Dead: The Impact of Shamans and the Cabbala Motivated by his encounters with Charles Robert StansfeldJones (1886-1950), alias Frater Achad, Lowry portrays the Consul of Under the Volcano as a “dark magician in his visioned cave,” regularly consulting Elizabethan plays and “numerous cabbalistic and alchemical books”.15 Indeed, the Consul possesses an esoteric, hermetic knowledge acquired by an assumed, shamanic ability to contact “the spirits of ancestors and the controlling forces of the natural world, or gods” in his trance-like state of consciousness.16 On his mystic crusade - a spiritual mission to discover death in life and life in death – he attempts to use the wisdom of the Cabbala to aspire, hallucinogenically, to a higher dimension of supreme truth and salvation by opening sacred portals connecting the natural and supernatural realms.17 It is through meditation and the imbibition of mescal and pulque – an ancient, sacred, ritualistic, alcoholic drink produced from the agave – that he transforms into a witch-doctor or shamanic priest, attempting to perform ecstatic “rituals of supernatural communication”.18 Seeking a harmonious cosmic order, the Consul endeavours to maintain a balance between the material and spiritual worlds. He aims to confer with the gods to avert misfortune, as did the Aztecs and the Zapotecs.19 On the one hand, Mercia Eliade (1907-86) assumes that a “primitive magician, the medicine man or shaman, is not only a sick man, he is, above all, a sick man who has been cured, who has succeeded in curing himself”.20 However, in the Consul’s case, his dabbling with the laws of nature has culminated not in an attainment of the transcendental power of love, but in the loss of “the knowledge of the Mysteries”.21 Unfortunately, he has become a victim of his own cabbalistic magic, as Lowry reveals when he explains: 7 The garden can be seen not only as the world, or the Garden of Eden, but legitimately as the Cabbala itself, and the abuse of wine […] is identified in the Cabbala with the abuse of magical powers […] à la Childe Harolde.22 From Cuernavaca to Oaxaca in the Quest for the Elixir of Life As with the Consul in Under the Volcano, a priest on a pilgrimage, Lowry too embarks upon a quest for the Holy Grail of Central Mesoamerican civilization. In his search for veracity, enlightenment, and redemption, he endeavours to cure the world by discovering a shamanic elixir of life.23 He is enchanted by Oaxaca to which he travels, referring to it in his letters as “the most lovely town in the world & with some of the most lovely people in it”.24 On his expedition he encounters the multilingual Zapotec, Juan Fernando Márquez whom he befriends and whose shamanic phantom he later retraces to Oaxaca. According to Douglas Day, as well as being a messenger for the Ejidal Bank and a dipsomaniac linguist, Juan Fernando possesses the expertise of a doctor, translator, adventurer, and chemist – that is, all the skills which our Consul is attempting to master.25 The real-life figures of Márquez and Fernando Atonalzin of Lowry’s “Garden of Etla” serve as models for the fictional Juan Fernando Martínez.26 In Dark as the Grave Martínez, a former friend and guardian spirit of Sigbjørn Wilderness, is the joint reincarnation both of the legendary Juan Cerillo and of Dr Vigil in Under the Volcano. Indeed, it is Martínez whom Sigbjørn pursues on his return journey with his wife from Vancouver to Cuernavaca to exorcize the ghosts, or phantoms which have been plaguing him since his last visit to Oaxaca.27 Whereas Primrose encourages him to attain a state 8 of harmony with life, Martínez enables him to do so with death and, paradoxically, with the natural environment, providing a cathartic medium for spiritual transformation, as a phoenix of renaissance. Sigbjørn is also aided by a ritualistic, voodoo cross which is depicted as a means of enabling the spirits of the dead, transformed into gods, to communicate with the living.28 In his quest to uncover the genesis of the indigenous Zapotec civilization, Sigbjørn’s trip to the high priest’s palace entails a physical descent to Mitla’s prehistoric, cruciform tombs, right down to the subterranean Column of Death. Indeed, derived from “Mictlan”, Mitla represents the land of the dead.29 On a simultaneous, metaphysical journey, Sigbjørn is transported to the underworld of Zapotec mythology. Luckily, he is to survive the potential perils of the lunar eclipse, Maximilian’s Palace (transposed to Oaxaca from Cuernavaca), and the temple of Mitla (“the City of the Moon”). Indeed, it is in the romantic setting of the Hotel La Luna on the Playa La Boquilla near Puerto Ángel on Oaxaca’s Pacific Coast that he is reunited with Primrose, who is portrayed as a lunar-goddess reborn.30 Enshrined in the worship of the deities of the Sun and the Moon, as is evident from the excavations of the pyramids at Monte Albán (dating back to 500 B.C.) and at Teotihuacan (to 100 A.D.), these cosmic enigmas and ancient rituals captivated Lowry who modestly acknowledges that he “did, however, live in Oaxaca for a time, among the ruins of Monte Albán and Mitla”.31 Named after a Mexican tree whose wood and flowers are white like the moon at night, Monte Albán, or ‘White Mountain’ - as well as being a significant socio-economic and political centre - was famous too for its astronomical Building J, enlivened by the veneration of Zapotec gods. 9 Conclusion With their roots in the rituals of ancient Aztec and Zapotec culture and civilization, as illustrated by the Mexican Day of the Dead, Under the Volcano and Dark as the Grave provide us with a mirror of Malcolm Lowry’s cosmic and shamanic phantoms. In his strife for cultural healing and spiritual regeneration, by entering “the soul of a past self” through Sigbjørn Wilderness in Dark as the Grave, he comes to terms with the haunting spectres of his psychogeographic heritage. He does likewise in The Forest Path to the Spring when, having conjured up an animistic cougar, or puma, Sigbjørn confronts the wild forces of existence by means of a shamanic flight back to his Lowrian Wallasey childhood.32 The use of the pan-Mesoamerican shamanistic practise of nagual - whereby a human being is transformed magically into animal form - is reminiscent of the Consul’s afterlife companion, or guardian angel, in Under the Volcano where “somebody threw a dead dog after him down the ravine”.33 This action provides the Consul both with protection against evil spirits and a means of conveyance to the supernatural underworld, in accordance with Aztec and shamanic customs. As a culmination of Malcolm Lowry’s moral and spiritual trajectory, it is the sensuous lyrical novella of The Forest Path to the Spring which offers us a Utopian, harmonious glimpse of his aqueduct across the domains of the living and the paranormal underworld of the dead. Spanning the natural environment and the cosmos, it shrouds the fluvial, transformational emblem of Eridanus, the “river of life: river of youth: river of death”.34 Cascading from Dark as the Grave, Eridanus - the mythological gateway to Hades - acts as an axis mundi. “Imbued with a life-force or soul,” it bridges all 10 three levels of the shamanic cosmos, as does the Day of the Dead.35 In this respect, many Mesoamericans visualized the underworld as rotating on its axis at sunset, transformed from being a subterranean realm into the night sky. Hence, the stars and other celestial bodies were perceived by the Aztecs and Zapotecs as “inhabitants of the supernatural otherworld”.36 In The Forest Path we witness a rebirth in Man’s relationship with his environment: we are beckoned to heed the aquatic, centrifugal rhythms of an elliptical universe, reverberating in the Chinese concept of the Tao, the Way.37 Select Bibliography Ackerley, Chris and Lawrence J. Clipper, A Companion to “Under the Volcano”. Vancouver: U of British Columbia P, 1984. Atwood, M. A. Hermetic Philosophy and Alchemy. New York, 1960. Aztec Gallery Guide. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2002. Bareham, Tony. Malcolm Lowry. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1989. Bowker, Gordon. Pursued by Furies: A Life of Malcolm Lowry. London: Flamingo, 1994. Cross, Richard K. Malcolm Lowry: A Preface to His Fiction. London: Athlone, 1980. Dahlie, Hallvard. “A Norwegian at Heart: Lowry and the Grieg Connection,” in Sherrill Grace, ed., Swinging the Maelstrom: New Perspectives on Malcolm Lowry. London: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1992, 31-42. Day, Douglas, Malcolm Lowry: A Biography. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1973. Dixil, Neeta, accessed 17 January, 2011: www.hss.iitb.ac.in/courses/HS%20204/file3.ppt. Dodson, Daniel B. Malcolm Lowry. London: Columbia UP, 1970. 11 Downie, R. Angus. Frazer and the Golden Bough. London: Victor Gollanz, 1970. ---. James George Frazer: The Portrait of a Scholar. London: Watts, 1940. Doyen, Victor. “Elements Towards a Spatial Reading,” in Malcolm Lowry: “Under the Volcano”: A Casebook, ed. Gordon Bowker. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1987, 101-13. Dunne, J. W. An Experiment with Time. London: Faber, 1927. Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and the Profane, trans. William R. Trask. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1959. ---. Shamanism, Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, trans. Willard R. Trask. New York: Pantheon Books, 1964. ---. “The Yearning for Paradise in Primitive Tradition,” in The Making of Myth, ed. Richard M. Ohmann. New York: G. P. Putnam, 1962. Epstein, Perle S. The Private Labyrinth of Malcolm Lowry: “Under the Volcano” and the Cabbala. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969. Foxcroft, Nigel H, “The Shamanic Psyche of Malcolm Lowry: An International Odyssey”, CRD Research News 26 (Summer 2010): 18. Frazer, Sir James George. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998 Frosh, Stephen. “Psychoanalysis in Britain: ‘The rituals of destruction,’” in Bradshaw, ed., A Concise Companion to Modernism, 116-37. Grace, Sherrill E. “The Luminous Wheel,” in Malcolm Lowry: “Under the Volcano”: A Casebook, 152-71. ---. The Voyage That Never Ends: Malcolm Lowry’s Fiction. Vancouver: U of British Columbia P, 1982. 12 Interdisciplinary Encyclopaedia of Religion and Science, ed. by Giuseppe Tanzella-Niti and Alberto Strumia, accessed 28 July, 2004: http://www.disf.org/en/Voci/90.asp Lowry, Malcolm. Dark as the Grave Wherein My Friend is Laid, ed. Douglas Day and Margerie Lowry. London: Jonathan Cape, 1969. ---. “The Forest Path to the Spring,” in “Hear us O Lord from Heaven Thy Dwelling Place” and “Lunar Caustic”. London: Picador, 1991, 216-87. ---. “Garden of Etla”, United Nations World (June 1950): 45-47. ---. Selected Letters, ed. Harvey Breit and Margerie Bonner Lowry. London: Jonathan Cape, 1965. ---. Sursum Corda!: The Collected Letters of Malcolm Lowry. Ed. Sherrill E. Grace, 2 vols. London: Jonathan Cape, 1995 ---. Under the Volcano. London: Penguin, 1962. ---. “Work in Progress: A Statement”. Malcolm Lowry Archive, University of British Columbia, 1951. McCarthy, Patrick A. Forests of Symbols: World, Text and Self in Malcolm Lowry’s Fiction. Athens, USA: U of Georgia, 1994. ---. ed. Malcolm Lowry’s “La Mordida”: A Scholarly Edition. London: U of Georgia P, 1996. MacClancy, Jeremy. “’Anthropology’: ‘The latest form of evening entertainment,’” in David Bradshaw, ed, A Concise Companion to Modernism. Oxford: Blackwell, 2003. Martin, Jay. Conrad Aiken: A Life of His Art. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1962. Mellors, Anthony, Late Modernist Poetics: from Pound to Prynne. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2005. Miller, Mary and Karl Taube, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997. 13 Mota, Miguel and Paul Tiessen, eds, The Cinema of Malcolm Lowry: A Scholarly Edition of Lowry’s “Tender is the Night”. Vancouver: U of British Columbia P, 1990. Orr, John. “Lowry: The Day of the Dead,” in The Making of the Twentieth-Century Novel. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1987, 148-68. Rebollo, Alberto. “In the Footsteps of Lowry in Oaxaca,” The Firminist: A Malcolm Lowry Journal 1 (1) (October 2010): 41-44. Reilly, F. Kent III, “Art, Ritual, and Rulership in the Olmec World,” in Michael E. Smith and Marilyn A. Mason, eds, The Ancient Civilizations of Mesoamerica: A Reader. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000. Soustelle, Jacques. The Daily Life of the Aztecs on the Eve of the Spanish Conquest, trans Patrick O’Brian. London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 1961. Spence, Lewis. Arcane Secrets and Occult Lore of Mexico and Mayan Central America. Detroit: Blaise Ethridge Books, 1973. Spivey, Ted R. The Writer as Shaman: The Pilgrimages of Conrad Aiken and Walker Percy. Macon, GA, USA: Mercer UP, 1986. Sugars, Cynthia. “The Road to Renewal: Dark as the Grave and the Rite of Initiation,” in Sherrill Grace, ed., Swinging the Maelstrom: New Perspectives on Malcolm Lowry. London: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1992, 149-62. Tao/Dao - The Way, accessed 28 July, 2004: http://www.meaningoflife.i12.com/Tao.htm. ‘Taoism’, in Hutchinson’s Encyclopaedia, accessed 28 July, 2004: http://www.tiscali.co.uk/reference/encyclopaedia/hutchinson/m00 053331.html. Tucker, Michael. Dreaming with Open Eyes: The Shamanic Spirit in Twentieth-Century Art and Culture. London: Aquarian Thorsons, Harper Collins, 1992. ---. “Towards a Shamanology: Revisioning Theory and Practice in the Arts,” in H. Van Koten, ed., Proceeds of Reflections on Creativity, 14 21 and 22 April, 2006. Dundee: Duncan of Jordanstone College, 2007: ISBN 1 899 837 56 6. Vickery, John B. The Literary Impact of “The Golden Bough’”. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton UP, 1973. Wutz, Michael. “Archaic Mechanics, Anarchic Meaning: Malcolm Lowry and the Technology of Narrative,” in Joseph Tabbi and Michael Wutz, eds, Reading Matters: Narrative in the New Media Ecology. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1997, 53-75. Endnotes 1 Funding by the University of Brighton - in the form of the award of a onesemester research sabbatical - is acknowledged as having made possible this paper, an earlier version of which was delivered at the 2009 Malcolm Lowry Centenary International Conference, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 23 – 25 July, 2009. 2 Bronowski (1908-74) and Lowry were Cambridge contemporaries, both actively involved with the literary magazine, The Experiment (1928-31), to which Lowry refers in his letters: see Grace, Sursum Corda!, I, 70 and 120. He directly cites Bronowski, the eminent mathematician, biologist, and science historian (I, 75). 3 Lowry, Sursum Corda!, II, 364 and 379. See also Frazer, 377. 4 Lowry, Under the Volcano, 9. 5 The Cabbala, or Kabbalah refers to mystical Jewish teachings based on an esoteric interpretation of Hebrew scripture. 6 Lowry, Sursum Corda!, I, 315-16. 7 Miller and Taube, 74. 8 Soustelle, 112, quoted in Wutz, 66. 9 Lowry, Under the Volcano, 204. 10 Lowry, Dark as the Grave, 262 and 115. 11 Ibid, 263. 12 Lowry, Sursum Corda!, II, 367. 13 Lowry, Under the Volcano, 202-03, 216, 335, and 373-74. See Doyen, 112 and Grace, “The Luminous Wheel,” 162 and 165. In Lowry’s 1949-50 screen adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night (1934) we are reminded of Lowry’s vision of being “borne straight upwards into the night sky and the stars” as an “eternal reminder also that our being and will are elsewhere” (Mota and Tiessen, 241-42). In his correspondence Lowry writes of “the seven sisters & the myth of the Lost Pleiad” as being “the one cedar in the seven firs” (Lowry, Sursum Corda!, II, 367). 14 Interview held at Monte Albán on 6 November, 2010. 15 Lowry, Under the Volcano, 151, 206, 33, and 178. Treatises on science and magic by John Dee (1527-1608), the mathematician, astronomer, 15 astrologer, and adviser to Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) spring to mind. Lowry studied the Judeo-Christian metaphysical system of the Cabbala, participating in occult, magical practices with Stansfeld-Jones in the hamlet of Deep Cove near Dollarton: see Bowker, 321, Day, 294-95, and Lowry, Sursum Corda!, I, 529 and II, 201-03, 356, 360, 798, and 799. 16 Reilly, 374. See also Mellors, 131. 17 See Reilly, 374. 18 Ibid. It seems that the Consul - like Lowry himself – confuses mescal, the alcoholic spirit distilled from the agave plant (the genus of the aloe, or maguey) for mescaline, the psychedelic drug made from the peyote cactus. See Mellors, 132 regarding shamanic “spiritual excursions”. 19 Aztec Gallery Guide. See also Miller and Taube, 138. 20 Eliade, Shamanism, 27, cited in Spivey, 8 and 183. See also Tucker, “Towards a Shamanology” and Dreaming with Open Eyes. 21 Epstein, 27. 22 Lowry, Sursum Corda!, I, 595. 23 According to Mellors, a “healer of spiritual (i.e. psychological) and psychosomatic disorders,” the “shaman tends to be a member of the community who, having survived his own physical and/or mental illness, seeks to cure the ills of others” (131 and 133). 24 Lowry, Sursum Corda!, I, 183. 25 See Day, 242-43 and Bowker, 235. 26 See Day, 240-44 and Lowry, Sursum Corda!, I, 176 and 187. In his essay, “Garden of Etla” Lowry praises the Zapotec Fernando Atonalzin as representing “a people possessing a high degree of civilization and cultural genius,” including an “old Zapotecan religion” (45 and 46). 27 Lowry himself was constantly troubled by memories of Paul Fitte, his university friend who committed suicide in 1929: see Bowker, 97-100 and Lowry, Sursum Corda!, I, 3, 83, 85, and 93, and II, 701, 856, and 858. 28 In his correspondence Lowry refers to voodoo as “a religion, to be regarded with reverence, since […] it is […] based upon […] the supernatural as a fact that is fundamental to man himself” (Lowry, Sursum Corda!, II, 364). 29 See Spence, 49 and 110, cited in Sugars, 155. 30 Sugars, 158. 31 Lowry, Sursum Corda!, I, 315. 32 Lowry, Forest Path, 246 and 226, and McCarthy, Forests of Symbols, 206. According to Reilly, “Classic period Maya kings validated their right to royal power by publicly proclaiming their ability to perform the shamanic trance journey and transform into power animals” (374). 33 Lowry, Under the Volcano, 376. For further information on nagual and shamanic human-animal transformation, see Reilly, 374-75. 34 Lowry, Dark as the Grave, 261. See also pp. 26-27 and Lowry, Forest Path, 231. 35 Reilly, 374. 36 Ibid, 375. 37 See Lowry, Forest Path, 285-86, Interdisciplinary Encyclopaedia, and Tao/Dao - The Way.