Iara Cury Elizabeth Ewart Week 1: 19/01/2011 Anthropology and

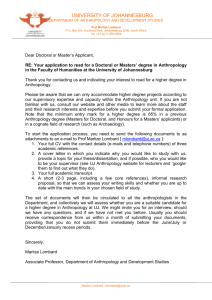

advertisement

Iara Cury Elizabeth Ewart Week 1: 19/01/2011 Anthropology and History: Twins, But Not Identical With its quite immodest name—the study of man—anthropology has carved for itself an all-encompassing niche, and such time and place where people have existed and lived, anthropology may claim it as its rightful, if not exclusive, domain. It is clear that nothing can keep anthropologists from wondering about the origins and evolution of human society and culture, just like nothing could keep them from investigating the farthest, most isolated and “exotic” groups of people on Earth. At the same time, social anthropology has built its reputation on the unpretentious method of ethnography, commonly focusing on local communities for its study of social organization and culture. Still, “limitations of time and energy” constrain the anthropological fieldworker to limited observation, unintentionally creating a “microcosm” out of its particular methods (Wolf, 1982, p.15). Fortunately, History and Anthropology1 seem to be developing an especially constructive relationship to the extent that anthropologists have begun to draw from the wealth of information available in historical archives and to answer time-sensitive questions that have hitherto gone unanswered. But before making the case for the potential uses of the discipline of History in Social Anthropology, it will be useful to establish the need for the study of humanity through work and interdisciplinary collaboration beyond the possibilities of localized fieldwork. Through their study of humanity, anthropologists have come to recognize the existence of certain social structures, like modes of production and kinship, social processes, like material accumulation and migration, and concepts like power, agency and ritual. But to understand an object of study, whatever it may be, is to understand its processes of formation and transformation (Bloch, 1986, p.194) as well as its functions and meaning. Furthermore, as Wolf argues in the introduction to his book, structures, processes and concepts are names we assign to quite fluid relationships and “relationship among sets of relationships” (1982, p.6). Much of anthropology entails a study over time of the flux of people, ideas and objects and resources around one or several different places—a study of how the unbounded ecological, economic, political, social and cultural elements of society affect each other over time. Simply put, anthropologists navigate everywhere between the microcosm of the individual and the macro levels of entire societies and global networks of people; not surprisingly, the timescale of studies matter as much as the complexity and subtlety of their subjects. Fundamentally, many anthropologists are interested in discovering or developing explanatory social theories about the world, which revolve around the linkage of causes and effects. Precisely because of this, Wolf states that we cannot hope to understand the present world without carefully tracing its development through history, producing History and Anthropology will be capitalized to denote the respective disciplines, as opposed to history as a sequence of events over time. 1 theories about this development, and matching such theories and history to changes and effects at the micro level (1982, p.21). Social theorizing is what demands the most rigorous and nuanced accounting of events, processes and connections, and in reality, many significant social changes were not recognized and understood until “placed in the crucible of history” (Evans-Pritchard, 1962, p.56). Perhaps on this empirical reality lies the popularity of historical materialism, leading the social sciences to forever engage in “one long dialogue with the ghost of Marx” (Wolf, 1982, p.20). In particular, anthropologists continue to tackle the intimate but ambiguous connection between a society’s mode of production, power structure, ideology, and more generally, culture, that can only be clarified through historical analyses. By means of his historical study of the Merina circumcision ritual, From Blessing to Violence, Maurice Bloch demonstrates the importance of connecting the anthropological interpretation of a social phenomenon to its historical life. He critiques the usual dichotomy within anthropology between symbolist and functionalist treatments of ritual, proposing that determining how a specific ritual changes over time, both in practice and cosmology, is the true revelation of its functions and meanings. In the case of the circumcision ritual, while no process of formation can be determined, a process of transformation can be derived from historical records and politico-economic contextualization (1986, p.183). Having a configuration of hierarchy yet vaguely sketching a cosmological order, the ritual has been able to continually adapt to social change while maintaining stability of meaning. Where “dominators” and “dominated” interact in pre-determined ways, Bloch’s perceptive interpretation is that the play reinforces existing power structures while providing feelings of belonging and even satisfaction to participants (p.191-2). His conclusion could not be reachable outside the timescale of a historical study, which delicately impugns the explanatory failure of previous theories about ritual on their extreme ethnographic focus. Having settled the ultimate importance of studying social subjects and concepts over time, it remains for us to recognize how history plays a part in contributing to the work and knowledge of the anthropologist. One of the vast subjects connecting Anthropology to History is the complex and controversial historical relationship between Western and nonWestern societies. Evolving from the “civilized” versus “uncivilized” colonial discourse to the “oppressor” versus “oppressed” post-colonial discourse to more recent discussions about agency, subaltern resistance, and emic hybridization, the historical recognition of non-Western peoples’ histories and influence on Western civilization has gained a strong foothold in the anthropological understanding of the world. Claude Levi-Strauss, in the book chapter “Race and History”, discusses processes of change in terms of how one group of people will synthetize many social, cultural and technological innovations over time, from sources both within and (frequently) outside the group. This interpretation of “progress” as a probabilistic and cumulative gamble devolves much credit to the rest of the world, and in Levi-Strauss’ view, obliges the conscientious embracing of human diversity (1973, p.361-2). Wolf, in Europe and the People Without History, makes the argument that the West evolved in the tightest interconnection with non-Western peoples and geographies, whose societies were as dynamic as any other supposed “civilized” ones. If the history of the accomplishments and struggles of “uncivilized” peoples is missing, it is due to the biased or myopic perspective of past social scientists and historians (1982, p. x). In a similar vein, Marshall Sahlins’ article, “Cosmologies of Capitalism”, critiques the patronizing opinion that non-Western have valiantly resisted but capitulated to the forces of Western cultural and economic hegemony (1994, p.413). His historical examples of 18th and 19th century imperial China, Hawaii and Northwestern America demonstrate that local populations were (and presumably still are) actively incorporating goods and ideas into their local social contexts for their own purposes. Based on events and societies washed away by the sands of time, hidden under the biased records of established history, few of these conclusions could be drawn purely from ethnographic fieldwork and without careful archival work. Yet History as a discipline has evolved as much as anthropology over the last century, and though the discourse of long timescale historical projects is promising, the practice of History is as challenging as the practice of Anthropology. Evans-Pritchard, in his essay, “Anthropology and History”, points out that despite similarities in method and subject matter, History may be bound to the study of the public sphere, of political and economic affairs, and of dominant perspectives. Anthropology, by virtue of its personal encounters with informants, is obliged to answer more intimate questions about the domestic, familial and marginal spheres (Evans-Pritchard, 1962, p.59). This bias is also reflected in the fact that History has “historically” focused on documents produced by “official” or sociallydominant sources such as colonial officials, missionaries, and traders; oral narratives and “unofficial” documents, for their part, have gone unrecorded or ignored based on their “questionable” validity. Through historiography and the self-reflexivity elicited by the postmodern current of past decades, both History and Anthropology have come to look at themselves with a critical eye. Can History be objective? Do multiple histories exist through multiple perspectives? Does that lead the scholar to relativism? On Anthropology’s side, what is the meaning of cultural continuity and change? Whenever anthropologists turn to the archives in search of historical information, they must bear all of these questions in mind and to recognize the limits of past and present written records. In fact, perhaps one of History’s greatest contributions to Anthropology is on the history of Anthropology itself (Evans-Pritchard, 1962, p.57). Forcing anthropologists to face the evolution of their own subject—with its transitions from armchair study to functionalism, structuralism and all subsequent “isms”, History is the permanent reminder of the fluidity of ideas and theories about the world. For example, what was (is) the connection between anthropologists and (neo)colonialism? A discipline is always a product of its time; in its permanent struggle against ethnocentrism and evolutionism, and even academic “imperialism”, the longstanding lesson is that the anthropologist must thread forward with constant care. Useful as History may be to Anthropology, however, an essay about the major role of history in the study of humanity runs the risk of overshadowing one of Anthropology’s strengths—its perspective on human agency and its focus on lived experience. Even though participant observation maybe not bring to the fore all of the relevant facts, historical relationships and geographical networks, it is an indispensable half (or likely much more than half) of the work of understanding people, society and culture. Taking anything less than a long and hard gaze at the individual and his social and physical environment is to risk neglecting the depth and complexity of human experience and to risk assuming, in some form or another, a determinist view of social life. In its reconstruction of history, History the Discipline may benefit from resisting a tendency towards dominant-biased, teleological impressions; in its reconstruction of history, Anthropology the Discipline must endeavor to illuminate the dynamics between real personal choice and social determination. On such an understanding depend our actions and motivations in everyday, microscopic life. Bibliography Bloch, M. 1986. From Blessing to Violence Cambridge: CUP. Evans-Pritchard, E. 1962. ‘Anthropology and History’ in Social Anthropology and other essays London: Faber and Faber. Levi-Strauss, C. 1973. ‘Race and History’ in Structural Anthropology Vol2 London: Penguin Books. Sahlins, M. 1994. Cosmologies of Capitalism: the trans-pacific sector of “the world system”. In Dirks, N., G. Eley & S. Ortner (eds) Culture/power/history: a reader in contemporary social theory Princeton: Princeton University Press. Wolf, E. R. 1982. Europe and the people without history : with a new preface. Berkeley ; London, University of California Press.