Student Example 2 - U

advertisement

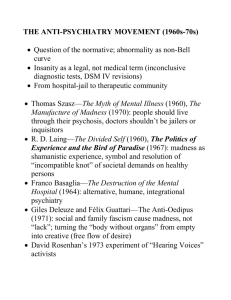

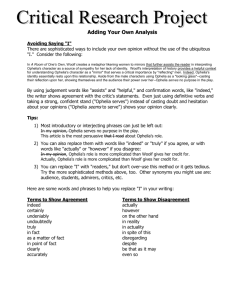

1 Sara Deegan [published by permission] [date] Public Argument The Madness of Virginia Woolf: A Psychoanalytical Study of Shakespeare’s Sister I contend that Woolf suffered from manic depression, a neurological disorder, by juxtaposing the myth of Ophelia and hysteria from scientific inquiries in the genre of mental health. By exploring postmodern psychoanalysts that frame Woolf’s depression in terms of Freudian oedipal and preoedipal complexes, who refute bipolar disorder as a psychiatric condition and discourage genetic research by portraying mental illness as a cultural myth and gender stereotype, Ophelia symbolizes a posthumous paradigm of the feminine archetype in male authored psychohistory. The subtext of women and hysteria often overshadows the scientific study of mental illnesses and stigmatizes mental health patients seeking treatment, yet, claims the vast majority of the uncertainties plaguing psychology today. Research compels societal progression; mental disorders pose a serious public safety concern and genetic research is necessary for improved treatment options for patients. Psychoanalytic history suggests Woolf’s feelings of female impotence and desire to penetrate the masculine explain her series of psychotic events. According to the Freudian model, the female artist manifests as the mad woman, i.e. Ophelia, but never as the creative genius, i.e. Hamlet. Woolf testifies in “Shakespeare’s Sister,” that “it would have been impossible, completely and entirely, for any woman to have written the plays of Shakespeare in the age of Shakespeare” (A Room of One’s Own, 39). Women’s madness represents biological dysfunctioning, Ophelia’s death conveys male authored subtext of the historical and cultural perspective of women and hysteria. While Hamlet struggles with moral alternatives, his madness 2 compels him to avenge his father, whereas Ophelia’s madness is biologically preordained and inevitably results in her immediate passage into passive insanity and subsequent death. Historically, Freudian thinking is the unspoken values and unconscious assumptions that fortifies common cultural stereotypes about the creative woman (Caramagno, Flight of the Mind, 8). One is forced to question if oedipal and preoedipal Freudian interpretation of pathology is relevant to our modern scientific inquiries, “her [Woolf’s] supposed flight from sex, or her morbid preoccupation with death--all the favorite Freudian themes which, not coincidentally, sustain sexist assumptions about the nature of the creative woman” (2). Psychoanalytical interpretations limit our scientific understanding of the brain and undermine the creative woman by perpetuating the social stigma of mental illnesses. Ophelia serves to illustrate what little we know about the way the brain functions, whether or not this image is an accurate portrayal of neuroscience. A woman restrained by misogyny reveals the feminine archetype in an oppressive culture as a gender stereotype, the madwoman, a powerful figure, rebels against patriarchal norms and becomes of a transgender nature, the “monstrous feminine” (Ussher, The Madness of Women, 153). Ussher argues that hysteria stems metaphorically from a woman’s reproductive organs due to her defiance of gender norms (153). Hysteria was once a common medical diagnosis, many women in asylums were forced to endure procedural hysterectomies, the surgical removal of a their cervix and uterus. Showalter argues in “Representing Ophelia: Women, Madness and the Responsibilities of Feminist Criticism,” because our interpretation of Ophelia depends upon our cultural attitudes, then if we view Ophelia as a figure of femininity in a patriarchal culture, i.e. the “object of Hamlet’s male desire,” her story serves as psychoanalytical criticism of femininity, bringing “to the foreground the issues in an ongoing theoretical debate about the cultural links between 3 femininity, female sexuality, insanity and representation” (1). For instance, Ophelia proclaims to think nothing and Showalter argues that nothing, in a patriarchal society, equates female sexuality (2). Hamlet responds: “That is a fair thought to lie between maids’ legs” Ophelia states, “what is, my lord?” Hamlet retorts, “nothing” (3.2.111). Ophelia thinks nothing in her brain because nothing lies between her legs. Ophelia acts as a catalyst for Hamlet who paints a derogatory portrait of women as castrated men. French psychoanalyst Lucelrigaray proclaims that women’s sexual organs “represent the horror of having nothing to see” (Showalter, Representing Ophelia, 2). Even Ophelia’s name possesses phallic symbolism, like her defiance of gender norms, O represents nothingness and the castrated female (2). Similarly, Woolf remarks that the madwoman is almost never portrayed as intelligent. In “Shakespeare’s Sister,” she notes that “it is unthinkable that any woman in Shakespeare’s day should have had Shakespeare’s genius” (A Room of One’s Own, 41). In order to discern cultural representation from psychiatric illnesses, Showalter notes that Hamlet, the “melancholy hero’s...intellectual and imaginative genius curiously bypassed women” (Representing Ophelia, 4). In Elizabethan drama disheveled hair symbolizes rape and the “dutiful daughter” becomes the embodiment of female pathology due to her hopeless oedipal complex, by explicitly giving away all her “wild flowers and herbs,” while symbolically dressed in white and adorned with flowers in her hair. Ophelia deflowers herself, then passively drowns and vanquishes from despair (3). Likewise, Wolf’s desperate return to the womb of feminine fluidity, as opposed to “masculine aridity,” and suicide by drowning in a sea of troubles, symbolizes the feminine archetype (4). “Yet genius of a sort must have existed among women...but certainly it never got itself onto paper,” Woolf speculates (41). Shakespeare’s metaphor of the repressed Ophelia portrays women and madness in the context of cultural perspectives. 4 Psychoanalyst Ussher insists that mental illness likely results of discontent in the context of a woman’s life and scrutinizes biochemistry as a possible theory for internal pathology. Female madness is a societal construction by a patriarchal culture designed to discipline women that deviate from gender norms, yet, Ussher excludes the possibility of a biochemical or neurological disorder (The Madness of Women, 14). Similarly, Showalter reveals that the myth of “Ophelia had begun to infiltrate reality, to define a style for mad young woman seeking to express and communicate their distress” (Representing Ophelia, 4). Ussher claims, however, that a woman suffering from a mental disorder likely experienced sexual abuse, violence and oppression, due to societal constraints (The Madness of Women, 12). Ussher asserts that “madness is a gendered experience” (12). Yet, Jamison notes that although equal numbers of men and women suffer from bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, affecting approximately one percent of the population, the social stigma affects more women than men (Manic Depressive Illness and Creativity, 45). Ussher trivializes mental illness in women, and offers no explanation for the occurrence of mental illness found in men: “we [women] signal our psychic pain, our deep distress, through culturally sanctioned symptoms, which allows our distress to be positioned as real” (9). The author explains that psychosis is a psychosomatic response to an oppressive or restrictive patriarchal system, dismisses verifiable evidence and research about the effects of genetics on neurological disorders and offers an obsolete psychoanalytic history of hysteria and women instead. Also, Jaspers speculates that mental illness is a complete fabrication, he states that “from time to time in psychiatry, there emerge diseases which constantly enlarge themselves until they perish from their own magnitude” (Ussher, The Madness of Women, 51). However, Mondimore argues that mania and depression date back to the ancient Greeks recorded by Soranos of Ephedrus, a physician in Rome in 98-177 A.D. (Kraepelin and Manic 5 Depressive Insanity, 49). In 1801 Pinel argued that mania was a periodic condition, occurs cyclically, and insisted on humane treatments for patients labelled insane (49). By 1971, Kraepelin described modern day diagnoses of mania and melancholia characterized by periodic insanity (50). Mondimore argues that Kraepelin’s work on manic depression and mental illness in the mid to late 1900’s composes most of our modern diagnostic system of psychiatry (51). Conversely, Ussher simplifies madness to a mere gender disorder resulted by trauma that manifests in the brain as psychopathology. According to Ussher, madness in women is merely subjective labels of female deviant behavior such as aggression, violence, recklessness, insomnia, depression, exhaustion, anxiety, etc. in a culturally sanctioned context and that no woman is immune to pathology or the “ascription of deviance” (The Madness of Women, 4). The assumption that a woman suffering from psychosis, which likely resulted from trauma (primarily sexual abuse), infiltrates the cultural myth of madness. Ussher clarifies, “women diagnosed as hysterics in the nineteenth century might have experienced distress...in response to an oppressive social...context…violence and sexual abuse, so might the women diagnosed with depression, PMDD, BPD or PTSD today” (11). According to Ussher, all psychiatric illnesses are treated alike and stem from the same cause, i.e. trauma. She applies subjective labels to mental illnesses and symptoms, then builds her argument on the cases of individuals that were misdiagnosed with a psychiatric condition due to a repressive cultural context or arrogant physician. However, a leading cause of misdiagnosis is our “imprecise use of scientific language” and misapplication of labels to people that may or may not be sick (Flint and Kendler, The Genetics of Major Depression, 493). Ussher uses words like mania and anxiety interchangeably, paints a portrait of the mad woman as damaged and frail in response to patriarchal oppression, but offers no reasonable explanation for the occurrence of mania in patients, a neurological condition, and 6 argues that women are inherently mad. Women deviate from the cultural norm, which is male: “women’s madness is both a myth--a culturally constructed label for distress or deviance” (14). Ussher then explores why women choose to become mad, perpetuating the stigma of mental illness by attributing hysteria to a historical and cultural fabrication that continues to affect women only in the context of their lives. Ussher states that madness is a woman’s psychosomatic reaction to deeply embedded psychological issues: “I not only challenge the legitimacy of these ‘disorders’ as objective diagnostic categories, but also explore how and why women come to experience distress and then see themselves as mad” (7). Regardless, Psychobiographer Caramagno asserts that Woolf did not become a great artist because she was a neurotic. Caramagno declares that these “sexist accusations” portray the creative woman as “damaged,” “fragile” and “oppressed” like a “wingless bird” (Flight of the Mind, 8). Caramagno encourages a scientific study of the brain for explanations of mental illnesses rather than speculation. He argues that Woolf did not suffer against a “twisted desire to remain ill,” but suffered from a neurological condition: “Neuroscience tells us some very disturbing things about how complicated and problematic it is to ascribe meaning to events” (2). While geneticists continue their diligent research for a deeper understanding of how the brain and environment function together, psychoanalyst Ussher argues that psychosis is a subjective label, thereby limiting etiology. Whereas psychoanalyst Ussher fails to account for mania, Bond attributes mania to psychosexual development and repressed anger (Who Killed Virginia Woolf, 22). Bond admits that “manic depression has an inherited, probably metabolic structure,” refers to family genealogy, then searches for an inherently psychoanalytical root to Woolf’s illness (23). Bond reveals that even Freud hardly applied two short references to mania in his entire work, then 7 draws a comparison between childhood sexual development to manic states, depicting Woolf as a child in desperate need of her mother’s approval (22). Bond proclaims that “many of her major novels ended with Woolf entering a psychotic episode” (37). This irrelevant information serves to undermine the creative woman and quality of Woolf’s work. Psychoanalytical interpretations of bipolar disorder denies scientific progress and the legitimate experiences of millions of men and women that suffer from mental disorders today who are not victims of violence or sexual abuse. For example, Modern British psychiatrist, Henry Maudsley, defines mental illness in terms of social conditioning as a woman’s response to limited upward mobility in a social structure (Ussher, The Madness of Women, 23). However, many women possess a greater opportunity for social and career advancement today than ever before. Caramagno explains that the Freudian “psychological model...is no longer relevant to her [Woolf’s] illness,” argues against a chemical or hormonal imbalance and describes a “neurological structure” instead (Flight of the Mind, 17). In 1925, Leonard Woolf, Virginia’s husband, declared that “they [the doctors] said that she was suffering from neurasthenia, not from manic depressive insanity, which was entirely different. But as far as symptoms were concerned, Virginia was suffering from manic depressive insanity” (Caramagno, Flight of the Mind, 17). Manic depressive illness accounts for Virginia Woolf’s madness and Caramagno points to critics that oversimplify etiology and fail to recognize “different types of depression (1) those depressions which result from psychological conflicts (e.g., those created by the trauma of sexual abuse), (2) those which are inherited genetically and/or physiological in origin (such as manic-depressive illness)” or a combination of the two (8). Any individual can become depressed, but bipolar is a genetic, heritable neurological condition. Caramagno argues that the “biological realities of manic depressive illness limit the critics freedom to tie events in Woolf’s 8 life to symptoms that seem metaphorically similar” (8). Psychoanalysts’ that attribute Woolf’s insanity to childhood trauma lack sufficient explanations for the severity of Woolf’s experiences with mania. Xu et al conducted an unbiased genome wide study on bipolar disorder by devised case control samples using a set of 2155 genes, the researchers point to “several genes of interest that support...findings for bipolar disorder” (Genome-Wide Association Study of Bipolar, 1). The authors of the genome study highlight a discord in the scientific community discovering the cause of mental illnesses. Determining gene moderation of environmental risk factors for a mental disorder, Flint and Kendler analyze that “for most of the 20th century, the focus was on ‘nature’ versus ‘nurture’...now it is increasingly recognized that a disorder may reflect genes and environment ‘working together’” (The Genetics of Major Depression, 484). While geneticists believe that a reaction cannot occur without a preexisting gene, behavioral researchers find this a “puzzling claim” (491). However, the answer would benefit society by discerning the proper “interventions to the appropriate subjects to prevent the disorder,” therefore, a genetic factor is imperative to “determining the [etiology] of psychiatric disorders” (493). Nature and nurture behave complimentary, social genetic and developmental psychiatry must work together to study the brain’s functioning in order to address the public safety concerns of undiagnosed and untreated mental disorders. Historically, hysteria could be explained as a woman’s reasonable reaction to a patriarchal society, however genetic research reveals the complex interaction of environment and genetics. Our myth of madness as a gender experience misconstrues a serious medical condition, stigmatizes the mental health patient and discourages humane treatment options, which can prove treacherous to the individual as well as society. 9 Works Cited Bond, Halbert Alma. Who Killed Virginia Woolf: A Psychobiography. Lincoln: iuniverse, inc., 2000 Print. Caramagno, Thomas C. The Flight of the Mind: Virginia Woolf’s Art and Manic Depressive Illness. 1992. London, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, Ltd., 1995. Books Google. Web. 9 Mar. 2014. Flint, Jonathan, Kenneth S. Kendler. “The Genetics of Major Depression.” Neuron 81 (2014): 484-503. Academic Search. Web. 20 April 2014. Jamison, Kay Redfield. “Manic-Depressive Illness and Creativity: Does Some Fine Madness Plague Great Artists? Several Studies Now Show That Creativity and Mood Disorders are Linked.” Scientific American, Inc (1997): 44-49. PBWorks. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. Mondimore, M. Francis. “Kraepelin and Manic-Depressive Insanity: An Historical Perspective.” International Review of Psychiatry 17 (2005): 49-52. Academic Search. Web. 21 April 2014. Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Bedford/St. Martin’s Edition. Susanne L. Wofford. Editor. Boston/New York: Bedford Books. 1994. Showalter, Elaine. “Representing Ophelia: Women, Madness, and the Responsibilities of eminist Criticism.” Shakespearean Criticism Vol. 35. (2007): 77-94. Academic Search. Web. 16 April 2014. Ussher M. Jane. The Madness of Women: Myth and Experience. New York: Routledge, 2011. Print. 10 Wei, Xu, et al. “Genome-wide Association Study of Bipolar Disorder in Canadian and UK Populations Corroborates Disease Loci Including SYNE1 and CSMD1.” BMC Medical Genetics 15:2 (2014): Academic Search. Web. 16 April 2014. Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. “Shakespeare’s Sister.” Gutenburg, 1929. Feedbooks. Web. 17 April 2014.

![Special Author: Woolf [DOCX 360.06KB]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006596973_1-e40a8ca5d1b3c6087fa6387124828409-300x300.png)