The Delaware Indians of New Jersey. From Colonial Times to the

advertisement

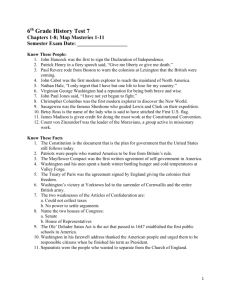

James Lone Bear Revey The Delaware Indians of New Jersey. From Colonial Times to the Present. I am happy to participate in this symposium on the Lenape or Delaware Indians, and to be able to talk about those Delawares who remained in the State of New Jersey since the Colonial period. As chairman of the New Jersey Indian Office, which is the headquarters for those of us who are descended from the original Lenape people, I have devoted many years to researching the history of my people. In this endeavor I enjoyed the help of many other Indians of Lenape ancestry and I am very grateful for their assistance. Together we accumulated genealogies, tribal rolls and historical documents relating to the Indians of New Jersey. There are many interesting facts about the Delaware Indians that have been overlooked by historians and scholars. I will talk about some of this today. We Delaware Indians in New Jersey, although separated from the main body of our people who moved to Oklahoma, Canada, Wisconsin and elsewhere, are very proud of our heritage. We are trying to preserve our history and culture and make it better known. Henry Hudson's voyage of 1609 opened New Jersey and New York to settlements by Europeans. Gradually Dutch, Swedes, English and others began to establish farming and trading centers on lands that had once belonged exclusively to the Lenape people and their ancestors. The name Lenape, meaning common person, was what the Unami-speaking people called themselves, but the English started the practice to call them "Delawares", a name that is still in use today. Both names, Lenape and Delaware, will be used in this paper. The newcomers' way of life was so very different from that of the Indians in manner of dress, housing, farming practices and especially religion, as to cause constant conflict and disparagement. The Europeans wanted the Indians' lands, but without the Indians. Superior weapons, epidemic diseases, rum and intimidation forced the Lenape people to part with their fields and forests and to move west. By the year 1710, most of the land in what is now New Jersey had been sold or bartered away to European colonists and land speculators, but despite the loss of their traditional homelands, many Lenape Indians remained in New Jersey. This paper will concern itself with those Indians who chose to stay. It has been stated that about eight to twelve thousand Lenape Indians lived in New Jersey and the surrounding areas at the time of European contact. Today, some scholars and Indian people, among them Nora Thompson Dean and Jasper Hill, would increase this number to twenty or twenty five thousand. Actually, the Lenape people, including the Unami- and Munsee-speaking Indians of the northern parts, occupied all of New Jersey, eastern Pennsylvania, southeastern New York and northern Delaware. The question concerning the numbers of Indians who remained in New Jersey has confused many writers. Part of the problem was record-keeping, part was due to geographical circumstances since New Jersey was divided into two segments after 1676. A line drawn northwest from Little Egg Harbor to a point on the Delaware River north of the Delaware Water Gap separated East Jersey from West Jersey (map 10). In 1758, the date of the Treaty of Easton, there were about three hundred Indians living in West Jersey and, perhaps, a hundred or more in East Jersey; the records are unclear. The journal and letters of the Presbyterian missionaries David and John Brainerd inform us about some of the Indians of West Jersey. In a letter dated August 24, 1761 Rev. John Brainerd tells us that Brotherton is a fine, large tract of land, and very commodiously situated for their [Indian] settlements, there are something upward of an hundred, old and young. He goes on to say, about twelve miles distant there is a small settlement of them, perhaps near forty, about seventeen miles farther there is a third, containing possibly near as many more, and there are yet some few scattered ones still about Crossweeksung. And if all were collected there might possibly make two hundred. This figure of two hundred is often, and mistakenly quoted as the number of Indians on the Brotherton Reservation. The History of the Colony of Nova Caesaria or New Jersey written by Samuel Smith (1765) indentifies the following Indian groups living in New Jersey in 1758: Ancocus (Rancocus) Indians, Crosswick Indians, Indians from Cranbury, Mountain Indians, Rariton Indians, and Southern Indians. In other parts of his book Smith says: There are about sixty persons seated here [at Brotherton in 1758], and twenty at Weekpink, on a tract formerly secured by an English right to the family of King Charles, an Indian Sachem (Smith 1765:484). The Indian name of King Charles was Machamickwon. Samuel Smith's list of seven Indian groups is interesting because of this number only the Cranbury, a primarily Christianized group of Indians, occupied the Brotherton reservation. Of the remaining six, only those living at Weekpink were close to this reservation. The Rancocus lived along Rancocus Creek in the vicinity of present day Mount Holly. The Indians at Crosswick were those who had chosen to remain after Rev. David Brainerd had relocated his mission to the new Indian town of Bethel in what is now Jamesburg. The Mountain Indians included those Delaware Indians who in Colonial times retreated into the Pohatcong and Schooley Mountains in northwestern New Jersey, and those Minisink, Pompton (Wappingers), Hackensack and Tappan Indians who remained in the mountains of the northwestern part of the state. The Raritan included those Indians who still lived on Staten Island, New York, and in parts of Burlington, Monmouth and Middlesex Counties in East Jersey. The Southern Indians were those native people who remained in the southern portion of the State and in the southern Pine Barrens. Many of these Indians were not within the area over which the Presbyterian missionaries Rev. David, and later John Brainerd, had jurisdiction and so they did not visit them or include them in their correspondence. These and other accounts demonstrate that many Indians were living both on and off the reservation. It is unfortunate that so many writers convey the impression that all of the Indians who remained in New Jersey were confined to Brotherton. In fact the majority were living in small communities some distance from this place. Reverend David Brainerd and his brother, John, had an exeptional concern for the Indians. Most of the European colonists and their descendants were concerned only with their own welfare, and few of them respected the rights and beliefs of the native people. Moreover, the Euro-Americans had superior weapons, rum, lethal diseases and an inflexible belief that might made right and that God was on their side. The Indians, unaccustomed to such arrogant behavior, unable to tolerate "fire water", and highly susceptible to the white man's diseases, were at a considerable disadvantage. In 1702 there were already more than 1,500 Europeans living in New Jersey, and by 1726 this number had reached 32,442, including 2,550 black slaves. By 1745 the Colonial population had almost doubled to 61,383 whites and 4,605 slaves. (Anonymous 1946:41). At this rate the Indian populations were quickly becoming an insignificant minority. The date 1745 was in certain respects a critical one for the Indians who were now impoverished and largely landless. The fur-bearing animals and the deer population had been hunted and trapped to the verge of extinction and the trade in furs and deer hides was the event of the past, for the Delaware at least. It was the time of decisision for the remaining Indians. Some of the Delaware did adopt European ways; they became farmers and craftsmen. Many had also learned the English language well enough to participate in the socioeconomic affairs of the time. Many of the Indians even adopted European names largely because the newcomers had difficulty pronouncing the Indian names, and because the Indians were trying to imitate the ways of the white people. Some Indians copied the names of Europeans whom they especially liked, or used the names the Europeans called them. Others liked the sounds of European words and used them. The Indians baptized into Christianity were given first names from the Bible, and last names of prominent Presbyterians and Quakers. Such European-sounding first and last names have continued to this day, but the more conservative Native Americans retained the custom of having Indian names. There were also instances in which the Indians kept their Indian names as their last names, for example: Ashatoma, Cuish and Moolis. Others simply rendered their Indian names into English. Last names as Stonefish, White Eye, Elk Hair and Fall Leaf are still found among Delaware and Munsee Indians. Marriages between Indians and whites were not uncommon. As early as 1705 it is recorded that an English woman from Monmouth County married an Indian man, and there were other instances of marriage both within the church, and without benefit of clergy. The Indians were using European style clothing by 1745, especially for ceremonial occasions. Moccasins were still made from Indian tanned deer hides, but the white man shoes and boots were very much desired by the Indians. The men wore trousers, shirts, coats and hats of European or Colonial fashions and Indian women adapted the Colonial frock of the time. Such clothing was usually given and added Indian touch with decorations made from beadwork and bangles of brass and tin. The more conservative Indians who preferred the old ways moved to areas far removed from the Colonial settlements. The largest Indian population was in central New Jersey, in Burlington and Monmouth Counties and in adjacent parts of contiguous counties. By the mid-eighteenth century almost all of the land in the State was owned by whites, as various tracts were so designated on the maps of the time. In fact, however, many interior areas were stil inhabited and used by the Indians. One important reason why the Delawares avoided the Colonial settlements was the fear of being captured and pressed into slavery. African slaves were used on many Colonial farms in New Jersey, and children and young persons of Indians descent were often abused in this same manner. Indians in dire poverty or distress sometimes sold themselves into slavery as their only means of surviving. Not all Delaware Indians were poor, however. Many Indians owned land which they farmed; they also owned cattle and even used slave labor. Such farms were usually small and seldom supplied more food than the family itself consumed. (Illustration: Early woodcut of "A Delaware Indian of the Colonial Period wearing Aboriginal Headdress".) Some Indian men joined the provincial armies, which not only solved their economic problems, but also fulfilled their warrior instincts. This tradition of Indians serving in the arm forces continued to this day. In fact, the Delaware Indians have fought in all of the American wars and have earned a fine record in the service of this country. Because the Lenape who remained in New Jersey were so few in numbers, they were of no concern to the provincial government. Most were pitiful, ragged, and landless people chased from place to place by the whites. The plight of these original people finally aroused the sympathy of the Presbyterian Church. Trough the "Society of Propagating Christian Knowledge", money was appropriated to send a missionary to work among them. Rev. David Brainerd, a sickly young man suffering from lung desease, was chosen to serve the Delaware Indians. He had been ministering to the Mahican Indians at Kaunaumeek (now Columbia County, New York), but in 1743, when he moved south to the "Forks of the Delaware" (now Easton) in Pennsylvania, his Mahican flock at Kaunaumeek joined other fellow converts at Stockbridge, Massachusetts where the main body of the Mahican tribe was living. While at the "Forks", Rev. Brainerd tried to convert the Northern Unami and Minisink Indians, but they refused his message. In 1745 he gave up on these people and devoted his full time to the remnant bands in New Jersey. Settling in the place called Crosswick, or Crossweeksung, as the Indians called it, in the northern part of Burlington County, he gathered a few Indian families together and formed a church. Rev. Brainerd tried to learn the Lenape language, but in this he was only partially succesful and had to rely upon native interpreters. He visited many places where the scattered Indians were living and was able to convert many women and children, but most of the men refused to listen to his message (Brainerd 1941). Rev. Brainerd also started a school at Crosswick and by 1746 this mission had a population of 130 Indians. The rapidly expending congregation caused Rev. Brainerd to think about finding a new location since the area was incapable of growing enough food to support the people. The nearby whites were also becoming apprehensive about the growing Indian population, and various types of harrasment ensued. As a result ot these conditions the group decided to move some fifteen miles north into Middlesex County. There, in late 1746, they formed a new town called Bethel. At that time the nearest town was Cranbury; therefore, the mission has often been called the Cranbury Mission. Bethel was actually a part of the present-day town of Jamesburg. The building used as a church and school was located in what is now Thompson Park in Jamesburg. The health of Rev. David Brainerd deteriorated rapidly and in 1749 he died of age twenty-eight years. His brother John, also a Presbyterian minister who had served for a time in Newark, New Jersey, now took over his brother's mission at Bethel (Brainerd 1941:31). Not all of the Christian Delaware moved to Bethel; twenty or so were living at Weekpink near present-day Vincentown in Burlington County. This Weekpink, known by the Indians as Okokathseeme, had formerly belonged to the Indian sachem known as King Charles. Although the Indians at Cranbury were trying to live good constructive lives and were learning the European methods of farming and stock raising as well as Christianity, they continued to be harrased by the surrounding whites who simply did not want to have Indians living so near to them. A prominent New Jersey Chief Justice, Robert Hunter Morris, went so far as to use a questionable deed to claim the lands occupied by the Indian Mission. The Quakers also became concerned about the problems of the native people and form the "New Jersey Association for Helping Indians". This organization sought to finance a new and larger tract of land; one that would not have a disputed claim. Unfortunately, this wish never came into being. By this time other problems were being created: the French and Indian War. Disgruntled Indians, many of whom had formerly lived in New Jersey, and who had been, or thought they had been, cheated by the English, now sided with the French. From bases in Pennsylvania they raided white settlements and farms in Northern New Jersey. As a result of these hostile actions the Indians in Bethel felt even more endengered. They were surrounded by whites who made no distinction between peaceful and warlike Indians, regarding all as potential enemies. The raiding war parties also considered the Christian Indians at Bethel to be traitors because they were not fighting the English. Caught in this dilemma the Bethel Indians appealed to Governor Jonathan Belcher of New Jersey. In 1755 Governor Belcher issued a law entitling the peaceful Bethel Indians to obtain a certificate proclaiming them nonhostiles, and as a form of identification they were given a red ribbon to wear around their heads. This precaution was necessary to distinguish them from the hostile Indians who were raiding in Northern New Jersey. In 1756, Governor Belcher felt compelled to put a bounty of 150 Spanish dollars on the heads of all hostile male Indians fifteen years of age or older. This bounty was to be paid if the Indian was brought to a jail or fort. Fifty Spanish dollars were to be paid to any one who killed a male Indian fifteen years of age or older, and who could produce the scalp of the slain Indian. The sum of 130 Spanish dollars was also to be paid for any enemy male or female under fifteen years of age, delivered to the government authorities. The Indians at Bethel and Weekpink were warned to stay within certain areas. No Indian was allowed to be carried across the Delaware or Raritan Rivers without permission from the Government. This decree was intended to stop young Delawares from crossing the rivers to join those Indians hostile to the English. On July 11, 1756 a treaty was signed in Pennsylvania between the Delaware Chief Nutimus and William Johnson which brought the Delawares closer to side of the English. The treaty also had the effect of ending some of the hostile feelings between the Indians and whites in New Jersey. The Quaker and Presbyterian leaders realized that the Indian's hatred for the English had been fused by years of mistreatment and distrust. A commission was therefore set up in 1756 by the Provincial Government of New Jersey to hear the Indians complaints and to try to rectify them. The following year the commission advised the legislature to pass appropriate laws to protect the remaining Indians. The commission also learned that the Minisink and Pompton Indians felt that they had not been paid for all of the land being used by the whites in northern New Jersey, and there was the problem at Cranbury and Crosswicks where the title of the land was in dispute. On February 20 to 23, 1758 a meeting was called at Crosswicks for various Indian leaders residing in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Teedyuscung , called the "King of the Delaware", and George Hopayock came from the Susquehanna River area in Pennsylvania, while twenty six Delawares represented the Indians of New Jersey. Five Indians were appointed to work together with the commission to solve the problems of land that had not been paid for. They also had an obligation to work out a solution for those Indians who wished to remain in New Jersey on land they fully owned and to be free from harrasment by the whites. The five New Jersey commissioners appointed by the act of 1758 were to make a settlement for the disputed lands.They were also charged with the responsibility of finding suitable land that could be purchased for a reservation for the Delaware Indians who lived south of Raritan River. An appropriation was made for 1,600 Spanish dollars of which 800 Spanish dollars were to be paid for the disputed lands, and 800 Spanish dollars to purchase land for a reservation. The claim by the Munsee (Minisink) and the Pompton Indians for unpaid lands in northern New Jersey was discussed at the meeting between Governor Bernard and the Munsee and Pompton leaders and their Iroquois representatives. It was agreed that the future meeting should be held at the "Forks of the Delaware River" at Easton, Pennsylvania. This meeting took place on October 8, 1758 when Governor Bernard of New Jersey and Governor Denny of Pennsylvania met with representatives of all Six Iroquois Nations, the Nanticoke, Tutelos, Unami, Munsee, Mahican and Pompton Indians. In all, 507 Indians attended this meeting. The land in northern New Jersey formerly owned by Minisink and the Pompton Indians was settled with a cash payment of 800 Spanish dollars. These two groups agreed to relinquish all claims to their New Jesrey lands, and two deeds were exchanged to make the payment final. Before attending the October 8, 1758 meeting at Easton, Pennsylvania the New Jersey Commission had already purchased 3,044 acres of land at Edgepillock on the road between Medford and Hammonton in Eversham Township, in what is now Indian Mill in present-day Shamong Township, Burlington County, New Jersey. They paid 740 Spanish dollars to Benjamin Springer, a white man, for 3,044 acres which contained some improvements including two houses, an orchard, fences, and two sawmills. One of the houses was owned by a white man, James Denight, and it was agreed that 100 acres surrounding his house was to be kept for his use. The rest of the land would be owned by the Indians tax-free. Governor Bernard named the reservation Brotherton after a place in England. It was the first and only Indian reservation in New Jersey, but it was not the first reservation in the Country as has often and mistakenly been stated by historians. A number of Indian reservations in Virginia, Pennsylvania, Long Island, New York and elsewhere predated the Brotherton Reservation, in some cases by one hundred years or more. The Mattaponi reservation in Virginia was granted by the Colonial House of Burgesses in 1658. (Map 11. The Brotherton Indian Reservation at Indian Mills in 1759, after a map in Woodward & Hageman's History of Burlington and Mercer Counties. A. Site of Rev. John Brainerd's house, B. Indian Burial ground, C. site of saw mill, D. site of original Indian saw mill, E. site of Indian log church.). The Brotherton Reservation became a refuge for the Christian converts of the Brainerd brothers. Other Indians living south of the Raritan River were also welcome but most of the non-Christian Indians refused to go there. The more conservative Indians were afraid to be concentrated in one place where they could easly be rounded up and killed. They continued to live in their own small communities, as did the Indians who were already freeholders, and those who were working on farms or as craftsmen. Rev. John Brainerd continued as the minister to the people of the Brotherton Reservation, and was appointed reservation superintendant. He was under the Synod of the Presbyterian Church headquartered in Philadelphia, and his assignment was for the people of West Jersey. Other Presbyterian ministers served the population of East Jersey. This is the reason why John Brainerd never mentioned having contacted Indians living in eastern and northern New Jersey. John Brainerd stayed at Brotherton until 1768, after which his work took him to Pennsylvania full-time. Stephen Calvin, the Delaware school master, who had married one of the daughters of the Indian sachem King Charles, continued to teach the reservation people. The promise of a happy future for those on the reservation soon began to fade because the land was unproductive. A meeting house and school, gristmill, blacksmith shop and trading store had been built in addition to the two sawmills and two houses that had existed before the purchase. The problem of harrasment by the whites continued. Trees were illegally cut down on the reservation and cattle belonging to neighboring whites were grazed on Indian lands (Brainerd 1941:22). By 1762 the reservation community began to have serious economic problems as well. They petitioned the legislature for money to buy food and supplies, but none was appopriated. That same year the gristmill burned down. As things continued to get worse, some of the Indians had to go to work on farms owned by the whites, and in nearby towns. After the Revolutionary war broke out, all help from the provincial government was cut off. Some of the Indian men went to work at the Atsion Forge making iron bars from pig iron obtained at Batsto, New Jersey. By the year 1774 it is said there were only about sixty adults living on the Brotherton Reservation full time, but even these figures are uncertain. In 1777 John Hunt, a Queker preacher, visited the reservation and reported that the few Indians remaining there were in "very low circumstances due to lack of food and clothing" (Esposito 1978:95). As a result, the Quakers provided food and other supplies to the destitute people. By 1796 those living on the land were in such dire circumstances that the State of New Jersey had to appoint three men to lease the land to white farmers with the payment going to the Indians. The short-lived experiment had failed. Only a few Indians were now living at Brotherton; the majority had gone elsewhere in the State, and white men were now farming the Indian's land. The contact with the Colonial whites who tried to help the Indians did, however, provide some important benefits. A few Indians were given the opportunity to become students at Princeton College in New Jersey, and at Moor's Indian Charity School located in Connecticut, and later New Hampshire; a school now called Dartmouth University. The Delaware Indians who attended Princeton College were Peter Tatami in 1753; Jacob Wooley in 1762; Bartholomew S. Calvin in 1770; George and Morgan White Eyes and John and Thomas Killbuck in 1789. The Delaware who attended Moor's School in 1754 were John Pumshire, Jacob Wolley (probable the same person who attended Princeton in 1762), Joseph Woolley; Hezekia Calvin in 1757, and interestingly, the female, Mirian Stores in 1761, Enoch Closs or Claus and Samuel Tallman in 1762. During these times, the Delaware tribe, now in Ohio, made at least two attempts, in 1767 and in 1771, to encourage the New Jersey Delawares at Brotherton to join the main body of the tribe. Later in 1777, when William Franklin was Governor of New Jersey, Stephen Calvin tried to represent the Brotherton Indians in disposing of the reservation land so that the people could move West. Among the names on the petition list were some that had been forged by Calvin, and as it turned out, many of these people had no desire to leave the Brotherton Reservation at that time. Governor Franklin informed those Indians who wished to leave that they were free to do so, and that those who wished to stay would continue to be under the protection of the Province of New Jersey. It is important that the Delaware were not alone in adversity and in their problems with their white nieghbors. The Indians on Long Island, New York, and those in Southern New England were also becoming more and more dissatisfied. They too tried to move away from their ancient homelands. In 1761, for example, David Fowler, a Mantouk Indian from eastern Long Island, journeyed to the Oneida Nation in Madison County, New York to relate to the Oneida the plight of his people on Long Island. The Oneida agreed to provide the needed land for the Long Island Indians and for the southern New England tribes who wished to move. In 1775 Samson Occum and Joseph Johnson, both Mohegan Indians of Connecticut, led the first group to Oneida, New York. Although all were Algonquian speaking people, their dialects differ so much that they had to accept English as their common language. These immigrants called their new settlement Brotherton (not to confuse with the New Jersey Brotherton). The Indians who made up Brotherton were Pequots from Stonington and Groton, Tunxis, Mohegans, and Niantic, all from Connecticut. The Narragansette came from Rhode Island, the Wampanoag from Massachusettes and Mantouk, Shinnecock and others came from Long Island. After the Revolutionary War the Mahican and allied tribes, living mainly at Stockbridge, Massachusettes, were also granted permission by the Oneida to settle in their territory. Their move began in 1783 and by 1786 all of those who had chosen to move were living at New Stockbridge, New York. It is necessary to relate this background in order to understand how the New Jersey Brotherton Indians were to fit with these brother Algonquians. The Stockbridge Mahican invited the unhappy New Jersey Delaware Brotherton Indians to join them at the Oneida, New York territory. The move was seriously considered by the New Jersey Brotherton because it was not as long as going to Ohio where the main body of the Delaware were residing. There also might have been a sentimental reason because Rev. David Brainerd had at one time served the Mahican as well as the New Jersey Delaware Indians. In 1801 the Indians who still lived on the Brotherton reservation, numbered about sixty-three. They petitioned the State of New Jersey for permission to sell their lands to obtain money to travel north to join the Stockbridge Indians. Three fourths of the Indians consented to sell the land. Their names as well as their petition are preserved in the New Jersey archives. The State consented to sell the land and appointed commissioners to arrange for the sale. The land was divided into lots of not more than one hundred acres each. These parcels were to be sold at public sale starting May 10, 1802. Twenty-two different buyers purchased the land for $2.00 to $5.00 per acre. Some of the money from the sale was given to the people to pay for the cost of the move. The remainder of the money was invested in United State's securities for their benefit. The sale of this reservation land, which was not approved by the Congress of the United States, was in violation of the non-Intercourse Act of 1790. This Act stated that no Indian lands should be sold without the approval of Congress. In 1802, Pomroy Jones, a resident of Westmoreland in Oneida County, New York reported that when the New Jersey Indians from Brotherton migrated to New Stockbridge, they passed his house in twelve wagons "for their baggage and with those to feeble to journey on foot" (Brainerd 1865:419). This probably meant that the able-bodied people walked all the way from New Jersey. He added that the wagons repassed, going back to New Jersey the next day, and he presumed the wagons had been hired. It is not known how many people made this trip to New Stockbridge; perhaps a study of family and individual names to whom lots were assigned will clear up this question in the future. It is known that the New Jersey Brotherton did not join the Long Island and southern New England Brotherton Indians, but affiliated instead with the Stockbridge Nation. They did not keep their tribal identity as shown in the following important document. [It is important to note that the name Brotherton occurs incorrectly both in the title and in one of the notations in the body of this agreement. The Brotherton Indians were those from southern New England and Long Island. The intended people were the Brotherton, the name by which the Indians from New Jersey Reservation were known. The name of the Muhheconnuck is also spelled inconsistently (ed.)]. This document read in part: "Article of agreement made [and] entered into at Vernon in the State of New York this 23rd day of September in the year one thousand eight hundred and twenty-three between Bartholomew Calvin, Johnathan C. Johston, Stephen Calvin, Jeremiah Johnston, Charles Tanseye chiefs and head men of the Delaware tribes of Indians formerly from the State of New Jersey of the one part & Solomon A. Hendrick, John W. Quinny, Austin Quinny, Thomas F. Hendrick, Benjamin Palmer, Frances Aaron & Sampson Auwohthommaug, chiefs and head men of the Muhheconuck [sic] Tribe commonly called the Stockbridge Indians of the other part. Witnesseth article first that the Muhheconuck [sic] Tribe or nation of Indians for and in considereation of the stipulation herein made of the part and behalf of the Brothertown [sic] Indians do hereby cede grant bestow to said Brotherton Indians and to their scattered brethren in the state of New Jersey, to them and to their offspring stock and kindred forever an equal right title interest claim with us the said Muhheconuck Tribe or nation of Inndians and are to be considered as a component part of the Muhheconuck or Stockbridge nation to all the lands comprehended within and described in the two treaties made at Green Bay... " (Wisconsin 1852:6, 7). From the signing of this 1823 article of agreement, the New Jersey Brotherton and the Stockbridge Indians acted together. This document not only identifies the Indian leaders of the two tribes of that time, but clearly indicates that they were aware of other scattered Delaware left in the state of New Jersey. Moreover, this article clears up the matter of the similarly named Brotherton and Brothertown Indians. The New Jersey Bratherton did not merge with the southern New England and Long Island Brothertown group as is so often and incorrectly stated. In 1822 the New Jersey Brotherton, now living with the Stockbridge, petitioned the New Jersey Legislature to request that the balance of their account, which now amounted to $3,551.23, be placed in a Utica New York bank. In this year and until 1824 the New Jersey Brotherton along with the Stockbridge and Oneida Indians and the Brothertown Indians, also moved from New York State to a new tract of land near Green Bay, Michigan territory, now the State of Wisconsin. This land was purchased jointly from the Menominee tribe. Some records state that about forty New Jersey Delaware ended up in Statesburg, now Kaukauna, Wisconsin. It was probably not until 1840 before all of those who wanted to leave New York did so. Some of the New Jersey Brotherton returned to New Jersey. Some later went to Wisconsin directly from New Jersey according to Stockbridge-Munsee tribal documents. It is known that Bathsheba Mulis, one of the signers of the land release of 1801, died at Egg Harbor, New Jersey in 1827; she probably never left New Jersey. In 1832 a delegation of Indians from Wisconsin, including both Delaware and Stockbridge Mahicans and possibly St. Regis Indian, came to New Jersey under the leadership of Barthlomew Calvin whose Indian name was Shawuskakung, meaning "Wilted Grass Place". He was seventy-six years old at the time, and the son of Stephen Calvin the reservation school master. Of the six-men delegation, only two were Delaware Indians who had formerly lived in New Jersey: Bartholomew Calvin and Jeremiah Johnston. Charles Stephen, Austin Quinney and Andrew Miller were Stockbridge, and Sampson Marquis was probably a St. Regis Indian affiliated with the Stockbridge. A probable reason why the Stockbridge Indians came with the two Delaware was that they were now acting as one people. Indeed, one of the Stockbridge representatives, Austin Quinney, had a special interest in coming because his wife was the former Jane Ashatoma who was born on the Brotherton Reservation on November 8, 1799. Austin Quinney's children would therefore be considered Delaware because Algonquian people trace their tribe and clan through their mother. The purpose for which this delegation came in 1832 was to request payment for the right to hunt and fish on all land in New Jersey south of the Raritan River regardless of ownership, as was stated in a separate deed. These Indinas felt that this right had not been paid for and had not been relinquished when the reservation was sold. A speech by Barthlomew Calvin to the New Jersey Legilature so melted their hearts that the sum of $2,000 was paid to the Indians for the purpose of relinquishing any further claims on New Jersey (Stewart 1932:83-84). The descendants of the New Jersey Brotherton are at present enrolled as members of the Stockbridge Munsee tribe of Bowler, Wisconsin and many still live on that reservation today. The Brotherton Indians who left New Jersey were by no means the last of the Delaware Indians in the State. The scattered Delaware in New Jersey, mentioned in the 1823 Agreement, continued to live here, usually in small communities or mixed in with the general population. For the most part, these Indians were located in the places mentioned by Samuel Smith. Today, their descendants are still living in New Jersey and New York. The official policies toward the Indians on the East Coast, first by the European colonists and later by the United States Government, changed from time to time as might be expected. Some of the early English lawmakers thought that they should adopt a policy of classifying the Indians as whites and then convert them to Christianity. They could then marry the Indians and through family ties and alliences be able to take over control of their land in a peaceful way. Thomas Jefferson also envisioned such a policy in settling the Midwest. The Indians could not agree to this policy and usually fought the invaders to protect their lands. The English Colonists then declared the Indians to be people of color and pagans. Intermarriage between the two races was looked upon as miscegenation and the Churches, as well as the Colonial Government, frowned upon such unions. With the Indians identified as non-whites and as pagans, the Europeans felt some justification in taking the Indians' land by any means. The English, for the most part, did buy the land, or traded for it in commercial goods. Such transactions were all properly recorded. The Indian's person was another matter, however, and many were captured and enslaved. As a result of oppression, or simply to retain their original way of life, many Indians moved inland and joined other tribes that had not yet been affected by colonial encroachment. The Indians who remaind within the areas of Colonial settlement were, of course, subject of Colonial policies. Certain Colonial governments regarded the defeated Indian tribes as nations, and dealt with them on a Nation to Nation basis. For some of these defeated Nations a parcel of land was set aside, away from the white settlements, to enable the Indians to have their own territory to occupy and govern - these were called reservations. The Indians were not to come to the Colonial nations except with permission. While there, the Indians were subject to special laws governing their activities. They were not citizens of the colonial "country" and had no status there. The Indians did, however, have a status on their reservations "country". As long as these lands existed, the individual tribes had a country. Moving off this land, or selling, reduced the Indians to a non-status person. This manner of dealing with the Indian people suited the early Colonial authorities and the settlers, but it was not at all agreeable to the Indians. As the colonies continued to increase in population and spread over additional ares, the Indians found themself under pressure to move further inland. Those to tried to maintain their tribal lands found themselves being slowly overrun. Harrasment of the Indians was one of the methods used by neighboring whites, and the Colonial Government permitted it to happen. Many of the early reservations were gradually reduces in size and now contained only a few acres. Those Indians who felt obliged to sell their land, as for example, the Brotherton Indians, had their nation dissolved and eventually lost their Indian status. The Indians who remaind were now part of the Colonial nation and although still Indians, they no longer had a unified homeland and their people were divided. This policy of dealing with the Indian tribes on a nation to nation basis continued after the formation of the United States, and even to the present. How the Colonial Governments and the United States Government counted its Indians can be seen in the following tabulations. Early Colonial censuses in some of the counties of New Jersey did list Indians people separately as early as 1709. Indians on the Brotherton reservation, however, were not counted in early times. The first United States census of 1790, which counted 3,929,214 people, had the following classifications: Free white males 16 years and upward including heads of families, free white males under sixteen years, free white females including heads of families, all other free persons, and slaves. The count omitted Indians who were not taxed and counted as other free persons if they were not slaves. The 1800 and 1810 Federal census included free whites, slaves, and free color persons, except Indians not taxed. The 1820 Federal census included free whites, slaves, and free colored persons, except Indians not taxed. The 1830 census recorded free whites, slaves, and free colored persons, and no mention is made of Indians. (In this and other censuses the Indians were included in the free colored person category). The 1840 census listed free whites, slaves, free colored persons and again no mention of Indians. The 1850 census listed whites, blacks, and mulattos but no Indians. The same identifications appeared on the 1860 census. The 1870 census had a wider range of racial classifications: whites, blacks, mulattos, Chinese, and for the first time, a place to enumerate Indians. The 1880 census left the racial classification up to the census-taker (this practice of allowing the census-taker to make the determination of an individual's race without asking continued until 1960). In 1890 the selection was White, Black, Mulatto, Quadroon, Octoroon, Chinese, Japanese and Indian. This census, for the first time, attempted to count Indians living on reservations and in the general population. The 1960, 1970 and 1980 Federal censuses were self enumerating in the statement of race, and people were allowed to classify themselves as to race. The 1890 Federal Census recorded 84 Indians in New Jersey; 1900 - 63; 1910 - 168; 1920 - 100; 1930 - 213; 1940 - 211; 1950 - 621; 1960 - 1,699; 1970 - 4,705; and 1980 - 8,394. In 1980, Indians were reported as living in all 21 counties of New Jersey with Essex County having the largest number, 1,050. The 1980 census also asked Indian people to list their tribe in a special box on the census form. A tabulation of the number of Indians belonging to a specific tribe will probably available sometime in 1984. The State of New Jersey also conducted a state census at mid-decade starting in 1855 and ending in 1915. The New Jersey census did not ask what race a person belonged to; instead the census-taker expressed his own opinion concerning which of three groups: White, Black or Mulatto, the individual belonged to. There was never a place to enumerate an Indian on the New Jersey State census, even though the Federal censuses after 1880 clearly indicated that Indians resided in the State. None were listed on the New Jersey State census. The Federal census prior to 1960 can not be relied upon to provide a true count of the Indian population in the United States. And the New Jersey State census is worthless in determining how many Indians were living in New Jersey, because Indians were never listed as such. In recent years, the Federal government has adopted a new policy of classifying the racial character of its citizens. The following information is derived from the Bureau of Census, United States Department of Commerce - General Population Characteristics (1962:VIII, IV). Race and Color: the term "color" refers to the division of the population into two groups designated as whites and non-white, the latter consisting of such races as the Negro (Black), Indian, Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, Korean, Asian Indian and Malayan races. "White" refers to people who have their origins in Europe. In recent years the term "White" has also been used to include persons whos origins are from North Africa and the Middle East. What does the Federal Government say about who is an Indian? There are many definitions used by various Governmental agencies. From early times the classification of an Indian depended on the degree of Indian blood or ancestry an individual had. When the Federal Government used the Nation to Nation bases, the Indian tribal membership roll was accepted as the bases for identification with an Indian Nation, and as an Indian. The general rule was to classify person with one fourth or more Indian blood or ancestry as an Indian, if that person considered himself or herself to be an Indian, and if that person used Indian as his or her racial classification. In 1950 the State of New Jersey also determined that a person with at least one-fourth Indian blood or ancestry could be classify as an Indian. In fact, however, many persons with one-forth or less Indian blood or ancestry do not consider themselves to be Indians. Federal and State records, and keepers of Vital Statistics, do not necessarily share the same criteria with respect to race. Until recently surveys of school-age students classified pupils as either white or colored. Couples applying for marriage licenses also had the same two choices. Even death certificates in most states list only white or colored. Given this choice, some Indians identified themselves as white, other as colored. In some states, Indians were recorded as white, but most states recorded them as colored and not as Indians. Now Indians and others are given opportunity to identify themselves. The Indian people take somewhat different view. They believe that an Indian is a member of an Indian tribe, nation, band or group. Such tribes, nations, bands or groups determine their own membership. The one-fourth or more Indian blood rule has become a part of many tribal by-laws with regard to Indian membership, Indians feel that there are really only two types of people, Indians and non-Indians. Earlier it was noted that Indians have served in the Armed Forces since Colonial times. Army muster rolls show many Indians recorded as Indians, other rolls give no racial designations. Many Delaware Indians fought and died for this country during the Revolutionary war and their name have been faithfully recorded and honored by the United States. In later years Federal armies were divided into white and colored outfits. During the Civil War, Indians of many tribes in the South fought on the side of the Confederacy and had units made up of Indian soldiers. In World War I the two classifications system was in use. Most Indians served in the White army although some chose to serve with the colored troops. In World War II there were still only two classifications - white and colored but by this time, the term colored had come to mean Black or Negro soldiers only. The white army in World War II included Indians, Orientals and others. Indians who served in the white army nevertheless had their discharge papers and records state that they were Indians. The 1980 census of New Jersey populations identified 8,394 Indians living here as part of the general population. These Indians dress like everyone else, live in houses and apartments, and work at every type of job. They drive cars and ride buses. In fact, there is very little that would set them apart from the general population. One would have to be an Indian or an expert on Indians to detect their presence. Several times a year are Indian gatherings and Pow Wows; at such times some Indians will don tribal costumes and sing and dance to the beat of the drum, and partcipate in ceremonies. Most others will take part in these events only in a limited way because they no longer own their native dress and do not know how to make it. Some of the Indians now living in New Jersey can speak their native language and do so when members of their tribe are present. Most have forgotten their native language and their families have not been able to speak it in generations. Most of the 8,394 Indians identified in the 1980 census come from tribes in other states; they are in New Jersey to work or go to school. Most Indians are quiet and will not discusse their Indianess unless they have to, because ridicule, disbelief and harrasment still come from the non-Indian populations. Besides the Indians who have come to New Jersey from various parts of the United States and Canada there are Indians from Mexico, Central America and South America. These are usually classed as being Hispanics. The few Indians that can trace their ancestry back to the original Delaware people and to Colonial times are a decided minority. The problem concerning the number of Delaware Indians now in New Jersey will be clarified when the final results of the 1980 federal census are made available, for then it will be known who among those surveyed consider themselves to be Lenape or Delaware Indians. The number may not be large, for many Indians are members of two or more tribes because of their parents. In such a case, the name of the first tribe listed will be counted. In the 1950's, an attempt was made to survey all of the Indian tribes and bands in the United States and Canada. Only fifty-one Delawares were identified in New Jersey. This figure was too low because only the organized Delaware were counted; those who did not belong to a known group were omitted. Of the acknowledged Delaware Photo: Sand Hills Indians. The late Johnson and Restelle Revey. Johnson Revey was descended from two New Jersey Indian families: his mother was a Johnson, his father a Revey. Restelle Revey had a Cherokee father named Richardson, and a Delaware Indian mother. or Munsee Indians, some were surely descendants of the Munsee-speaking people who remained in northern New Jersey. Until recent times some of these people were to be found on both sides of the border with New York State. Their family names appear in Army muster rolls and in other documents. In the southern part of the State there are also families that are still concious of their Delaware Indian ancestry. They have been mentioned in the several books about southern New Jersey. There are also descendants of the Rancocas Indians living in the Trenton area. Some genealogies contain old Indian family names. Many of their relatives with the same family names are found in Wisconsin, Oklahoma and Canada today. Those Indians who lived in the Pohatcong and Schooley Mountains about four generations ago all came down from the mountains to live in the towns in Morris County and elsewhere. Some of these Delaware Indians intermarried with Indians of Monmouth County years ago. The term Raritan was used more or less casually for Indians living south of the Raritan River in Central New Jersey. Earlier writers included the Indians on Staten Island, New York, as part of this group. The Indians who went to live in the Pohatcong and Schooley Mountains were in part Raritans. Some of the Indians who remained in Burlington County were among the ancestors of some of the people now living in the Pine Barrens. There were also intermarriages between Burlington County Indians with those who remained in Monmouth County. Of the Delaware Indian who remained in Monmouth County, some were farmers, others became carpenters and craftsmen. In Revolutionary War times, Indians from outside the State of New Jersey started to drift in. Cherokee and other Indians from the South came to Pennsylvania and then crossed the Delaware River into New Jersey. Some of these Cherokee Indians married with the Indians living in Monmouth County, thus bringing more Indian blood and some new family names. Many of these people, now in Monmouth County, married close relatives in order to keep their degree of Indian blood high. Around 1820 some of these Indian people went West. Those who remained continued to hold their farms, in some cases in the same family for over two hundred years. Others living near Eatontown, and elsewhere in Monmouth and Burlington Counties, took on new jobs or moved to New York State. After 1870, the shore area around what is now Asbury Park, was developed by a New York businessman who purchased five hundred acres of woodland bordering the Atlantic Ocean to build the summer resort. The Indian carpenters and craftsmen who went to work for him were such good workers that they were offered a piece of valuable property near the ocean on which to build their own houses. They decided against this land because they feared hurricanes. Instead, they looked for land further inland and in 1877 settled for fifteen acres near Indian Hill in what was then called Whitesville. This area became the Township of Neptune in 1879. Here some of the Indians settled, built their homes, and planted their gardens. The place was called Sand Hill and the people became known as the Sand Hill Indians. Other Indians who worked in the new summer resort did not settle on Sand Hill but continued to live in their old place. Most of the work at the shore was seasonal, and by 1890 the people were beginning to move away from Sand Hill. Some departed, but kept their homes for the summer. Finally, about forty-five to fifty years ago most of the Sand Hill Indians were gone. Some families went to New York City where they were able to find work or start their own businesses. Others went to different locations after selling or renting their homes to non-Indians. Crafts such as basket-making, beadwork, and hide tanning were part of the livelihood of these people, and they found ready market for what they made. In had been the custom to hold summer Pow Wows on the ground of one of the Sand Hill houses that had not been sold or rented. The last Pow Wow was held in 1949. The scattered people came from all over for this event. In earlier times outings were also held at Long Point at the end of the summer. The Sand Hill Indians maintained a chief and a four-man council until 1953. After that time the records were kept by one of the former councilmen until all had died. These tribal records are now preserved at the New Jersey Indian Office in Orange, New Jersey. The great majority of Sand Hill Indians have lived away from the Sand Hill for forty-five to fifty years or more. Today, people tend to mistake the local people who bought the houses from the Indians, for the Sand Hill Indians who left the area so long ago. The fact that white and black people may sometimes have the same last names as some Indians further adds to the confusion. In 1887 a list was made of the names of Indian people who lived in Monmouth County and elsewhere. The list includes the Indians that had intermarried with Indians from Morris and Burlington Counties, and their families. Indians who are living today can trace their Indian harritage to people on this list. The last person that was named on the 1887 list died at the age of ninety-five in 1977. Today, most people of Lenape or Delaware Indian descent live in Oklahoma, others are found in Wisconsin, Kansas, the State of Delaware, and Ontario, Canada. I am happy to say that some of us are still living in our ancestral homeland of New Jersey. James Lone Bear Revey References Cited Allinson, William Jr.: Shawuskukhkung (Wilted Grass), Bartholomew S. Calvin. The Monmouth County Historical Society, 1920. Anonymous: A Treaty Between the Government of New Jersey, and the Indians Inhabiting the Several Parts of said Province, Held at Crosswicks in the County of Burlington on Thursday and Friday the Eight and Nineth Day fo January, 1756 William Bradford Printer, Philadelphia, 1756. Anonymous: New Jersey: A Guide to its Present and Past, Federal Writer's Project, Works Progress Administration of the State of New Jersey, Hastngs House, New York 1946. Brainerd, Thomas: The Life of John Brainerd, Philadelphia 1865. ---------------------: Transcription of Early Church Records of New Jersey: John Brainerd's Journal (1761-1762) New Jersey Historica. Records Survey Project, Works Project Administration, Newark 1941. De Cou, George: The Historic Rancocas, Sketches of the Towns and Pioneer Settlers in Rancocas Valley. News Chronicle, Moorestown N.J. 1949. Esposito, Frank J.: Travelling New Jersey. William H. Wise Co., Inc., Union City N.J. 1978. Stewart, Frank: Indians of Southern New Jersey, Gloucester County Historical Society, Woodbury N.J. 1932. Smith, Samuel: The History of the Colony of Nova Caesaria or New Jersey, Burlington, N.J. James Parker 1765 (Reprinted: The Rerprint Co., Publ., Spartanburg, S.C. 1975). United States Department of Commerce: United States Census of Population, 1960: New Jersey. U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census, United States Government Printing Office, Washington D.C. 1962. Weslager, Clinton A.: The Delaware Indians. A History. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick N.J. 1972. Wisconsin Historical Collections: Lands for Stockbridge and Brothertown [sic] Indians in Wisconsin Historical Collections Vol. XV: 6,7. 1852. Personal Correspondence: Shiela Moed, Stockbridge-Munsee Indian Museum, Bowler, Wisconsin.