SOUND BITES What Can You Do When Your Doggie`s Nose is Out

SOUND BITES

What Can You Do When Your Doggie’s

Nose is Out of Joint?

Eric M. Davis, DVM, FAVD, Dipl. AVDC

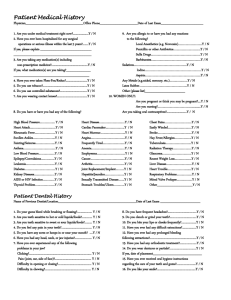

Although traditionally, the realm of dentistry includes healing the tissues between the lips and the tonsils, occasionally in veterinary dentistry, our horizons must expand northward. Two recent cases called for using oral surgery techniques including use of pharyngostomy intubation and application of an intraoral splint to stabilize multiple fractures involving the muzzle of dogs. In the first case, maxillary and nasal bone fractures resulted from a dog being hit by a car, and in the second case, a small dog was bitten by a larger dog. Both situations resulted in the rostral portion of the muzzle remaining attached only by skin; the maxillary and nasal bones were completely severed from the skull. Of well-intentioned individuals, it is often said “his/her heart is in the right place”. But as these cases illustrate, it is anatomically more important that your nose be in the right place.

Both of these dogs had their hearts in the right place, but their noses were completely askew!

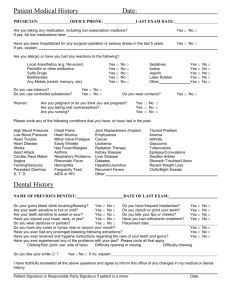

A 2 year-old mixed breed dog was referred to me by clinicians at the Cornell

University Hospital for Animals for stabilization of oral structures five days following vehicular trauma. When it became clear that the dog would survive and that her neurological status was improving, treatment to repair her mouth and muzzle was arranged. Despite the best efforts of her caretakers, the dog would not, or could not eat voluntarily. Upon presentation, the patient’s muzzle was shifted toward the right side and subcutaneous emphysema was evident when the head was gently palpated for symmetry, indicative of air escaping into the surrounding tissues. My treatment plan called for induction of general anesthesia to be followed by placement of a pharyngostomy incision to re-direct the endotracheal out through the patient’s neck. 1 In this manner, inhalant anesthesia could be maintained without the encumbrance of the tube exiting the mouth (Figure 2). More

importantly, the patient’s occlusion could be easily evaluated without having to remove and then re-intubate and secure the endotracheal tube each time (Figure 1).

By using the interdigitation of the teeth as a guide, the accurate restoration of the patient’s occlusion would simultaneously result in anatomical reduction of the major fragments of orofacial bones. There is very little tolerance for error in reconstructing the patient’s occlusion, and if the bite is off by more than a few millimeters, long-term suffering may result years after all of the wounds have healed. Adverse consequences of misaligned jaws following fracture fixation include the inability to completely close the mouth because of abnormal tooth to tooth or tooth to soft tissue contact, periodontal changes, temporomandibular arthritis, and facial deformity. It is difficult to justify dental extractions to facilitate closure of the mouth because of misaligned jaw fractures.

2

The palatal shelf of the maxillary bones, nasal conchae, vomer bone, nasal bones and maxillary bones were all fractured transversely, resulting in the rostral aspect of muzzle being severed from the skull between the right and left maxillary second and third premolar teeth (Figure 2). After debridement and closure of soft tissue wounds that had resulted in oronasal communication, the crowns of the maxillary teeth were cleaned, acid etched, and a U-shaped piece of 22 gauge orthopedic wire was bonded to the buccal aspects of several crowns using light-cured, flowable composite. Vaseline® was applied to the crowns of the mandibular teeth, and a self-cure composite material was applied to the arch of maxillary teeth and the wire. Before the composite began to harden, the dog’s mouth was quickly closed and the upper and lower dental arches were held in correct occlusion until the material had set. The layer of Vaseline® prevented the composite from adhering to the mandibular teeth, so when the mouth was opened, the composite firmly held the fractured pieces of maxillary bone in place, based upon the alignment of the teeth (Figure 3). Sharp edges of the splint were smoothed and contoured, and slight adjustments in the splint were made so that the mouth could freely open and close without interference. A temporary gastrostomy tube was placed and the patient was allowed to recover from general anesthesia. Sixty days after application of the intraoral splint, the bones had healed (Figure 4), with the only complication being xeromycteria. I’ll spare you the effort of having to dig out your Dorland’s or

Stedman’s Medical Dictionary … that spectacular word comes from the Greek words xeros (dry) and mykter (nose) and refers to excessive dryness of the mucous

membranes in the nose, usually due to damage to the lateral nasal gland or it’s nerve supply. The lateral nasal gland produces the serous secretion necessary to keep the mucous membranes covering the turbinates moist.

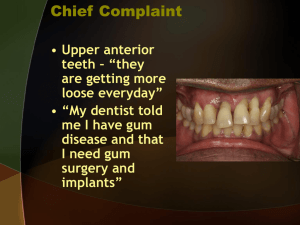

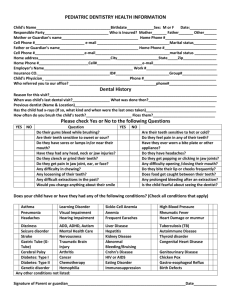

The second case involved a 3.5 year-old miniature pinscher bitch referred for repair of maxillofacial fractures after being bitten by a larger dog four days earlier.

Again, the entire muzzle of the dog was attached only by skin, as the bones that comprise the nose, nasal passages, and the palate, were all fractured perpendicular to the long axis of the maxilla at the level of apices of the right and left maxillary canine teeth (Figure 5). Damage was more severe in this case because the bite wound resulted in necrosis of portions of the palatal mucosa, the bone fractures were more comminuted because of the crushing effect of the bite, and the blood supply to the maxillary canine teeth was jeopardized because the apices were in the fracture line. Generally speaking, if teeth in a fracture line are not affected by periodontal disease, they should be left in place, since extraction would likely result in additional trauma to bone and soft tissue. Vascular damage to traumatized teeth may not be immediately apparent anyway, and the teeth should be radiographed and appropriately managed when the patient is presented for general anesthesia to remove the intraoral splint after the bone fractures have healed.

Acute extraction is recommended if teeth in the fracture line are obviously compromised by periodontal disease because loose teeth would affect the stability of the fracture repair and the infection would inhibit wound healing.

3 In this case however, I did extract two teeth in the fracture line. The right and left deciduous maxillary second premolar teeth (506, 606) remained present because of agenesis of the adult second premolar teeth (106, 206). Furthermore, to close the oronasal fistula caused by necrosis of palatal mucosa, I needed to advance oral tissue from the inner aspect of each cheek and the deciduous teeth were in the way of my flap.

Following placement of the endotracheal tube through a pharyngostomy incision, necrotic palatal tissue was resected and teeth 506 and 606 were sectioned, elevated and extracted. Buccal mucosa advancement flaps were created, mobilized and sutured into place thereby closing the oronasal fistula (Figure 6). The maxillary teeth were scaled, scoured with a slurry of flour of pumice and water, and acid etched with a phosphoric acid gel. A reinforcing wire was bonded to several teeth using a light-cured flowable composite. Vaseline® was applied to the crowns of the mandibular teeth and a self-curing composite was applied to the arch of the

maxillary teeth and the mouth was closed in occlusion as the composite hardened.

When the mouth was opened after the splint had set, the result was that the major fragments of bone were firmly held in alignment based upon the correct interdigitation of the teeth.

This technique allows for rapid return to normal function, anatomical reduction of major bone fragments based upon the patient’s occlusion, and stability to allow bony union. In addition to pain management, post-operative care usually includes temporary placement of a feeding tube to allow enteral feeding while the patient adapts to eating and drinking with the intraoral appliance in place. A chlorhexidine-based irrigation product is dispensed and the owner is instructed how to rinse under the splint to prevent accumulation of food residue between the composite and the teeth. Intermittent rechecks of the patient are usually scheduled, and after six to eight weeks, the splint may be removed under general anesthesia.

Displaced maxillary fractures are uncommon in dogs, but when they occur they often result in facial deformity, oronasal communication, instability, malocclusion, and obstruction of the nasal passages.

4 The delicate bones within the nasal passages are not easily repaired and air flow follows a path of least resistance.

Therefore, techniques for maxillofacial fractures should be focused on restoration of unhindered function of the teeth and jaws, rather than open reduction to enable bone fragments to be secured with plates, screws, and wires with little regard for occlusion. Consider this technique the next time you are faced with a dog whose nose is out of joint!

REFERENCES

1 Marretta SM, Schrader SC, Matthiesen DT. Problems associated with the management and treatment of jaw fractures. In: Marretta SM ed. Problems in Veterinary Medicine 1990.

Philadelphia; J.B. Lippincott, 220-247.

2 Nibley W. Treatment of caudal mandibular fractures: A preliminary report. J Am Anim Hosp

Assoc 1981; 17: 555-562.

3 Legendre L. Intraoral acrylic splints for maxillofacial fracture repair. J Vet Dent 2003; 20:70-78.

4 Legendre L. Maxillofacial fracture repairs. Vet Clin Small Anim 2005 35:985-1008.