BREWS_2

advertisement

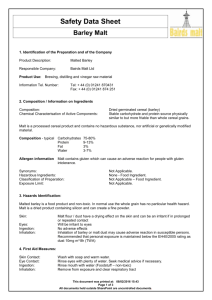

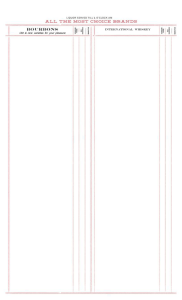

BREWS #2 Technical Topic: What’s a Malt Analysis Sheet and What’s It Good For? Beer Defect: Tannins Style Topic: BJCP Category 4 - Dark Lagers Thomas Barnes, 1/5/2011 Technical Topic: What’s an Analysis Sheet and What’s It Good For? What’s an Analysis Sheet?: A malt analysis sheet (sometimes called a malt spec sheet) is a document which describes the “vital statistics” of each type, or each lot, of malt. Since slight variations between different batches of malt can greatly affect malt character, professional brewers, and all-grain homebrewers striving for consistency from batch to batch, rely on malt analysis sheets when formulating recipes. There are two types of Analysis Sheets, Typical Malt Analysis and Lot Analysis. Typical Malt Analysis represents the maltster’s best estimate of the brewing properties of a particular variety of malt based on the current year’s barley crop. Typical Malt Analysis figures are readily available on any maltster’s web site and are useful when sourcing new varieties of malt or designing new recipes. Understanding the terminology in a Typical Malt Analysis is helpful if you wish to details about a particular malt’s color, diastatic power, potential extract yield and suitability for use with a particular mashing regime. Lot Analysis describes the brewing properties of a particular batch of malt. Even with modern levels of quality control, different lots of malt can have noticeably different lot analyses, which can affect the character of your brew! For this reason, if you’re trying to “dial in” a recipe so that it’s consistent from batch to batch, you must reformulate your recipe slightly every time you brew. Paying careful attention to differences between different lots of malt helps you do this. Getting Malt Analysis Sheets: Homebrewers don’t always have easy access to malt analysis sheets, especially lot analysis sheets, since they typically buy malt from a homebrew supply store rather than directly from the maltsters. If you are buying malt by the bag, better homebrew suppliers will typically supply you with a lot analysis, which they get (or should get) from the maltsters. If they do not, some manufacturers or suppliers have web pages where you can look up the lot analysis for your particular batch of malt. If you are buying your grain by the pound from a homebrew store, the store might have a lot analysis on file which you can look at, although this usually isn’t the case. Usually, the best they can offer you is a typical malt analysis for that particular malt. If the malt is sold out of large bags, however, you might be able to get the lot number off the bag and get a lot analysis directly from the maltster. The lot number should be printed on each bag. If you’re lucky you can find the lot analysis on the maltster’s web site. If you’re not so lucky, you might need to telephone, email or fax them. Reading a Malt Analysis Sheet: At minimum, an analysis sheet should provide information about color, extract potential, mealiness (friability or vitreosity), moisture percentage, protein percentage (total and soluble) and size assortment of the malt. For base malts, the analysis should also include diastatic power. Tests and measurements are standardized by the ASBC (American Society of Brewing Chemists) or the EBC (European Brewers Convention), but exact information provided will vary from company to company. Specialty malts typically won’t have complete analysis sheets, especially for traits such as diastatic power. A typical malt analysis sheet might look much like Figure 1. Reading the top columns from right to left, the abbreviations are: Barley Type: Two-row or six-row barley will be specified. Practically, this sort of information is limited use compared to other aspect of the analysis sheet. Barley Variety: Certain types of barley are traditionally preferred for certain types of beer and different strains of barley impart different flavors and aromas to beer. Strains such as Optic and Maris Otter are typically used for English ales, while strains such as Harrington are associated with certain types of American ale. While it’s not likely to be mentioned on the analysis sheet, the location where Fig. 1. Typical Malt Analysis Sheet Barley Type Barley Variety Assortment 7/64 Min. 6/64 Min. Thru Max H20 % Max. Color ASBC Deg. Lov. Brewers Malt ESB 2-Row Harrington 80 5.0 4.0 3.0-4.0 Colored Malt Vienna 2-Row Harrington 80 5.0 4.5 5.0-6.0 Munich 2-Row Harrington 80 5.0 4.0 9.0-11.0 10 Munich 2-Row Harrington 80 5.0 4.0 30-35 30 Specialty Honey 2-Row Harrington 80 5.0 4.0 20-25 Malt Organic 2-Row Harrington 80 5.0 4.5 1.8-2.8 2row Pale Organic 80 15 4.0 1.3-2.8 Pilsen Organic 70 25 4.5 1.8-2.8 Wheat Data taken from: http://www.specialtymalts.com/gambrinus/malt_analysis.html Protein Max. Sol Total S/T Extract Dry Min. FG CG F-C Diff. Max. D.P. Min. Viscosity Max 6.0 11.0 53.0 82.0 80.0 2.0 90 1.60 6.0 6.0 12.0 11.5 53.0 53.0 80.0 80.0 79.0 79.0 1.5 1.5 90 90 1.60 1.60 6.0 11.5 53.0 80.0 79.0 1.5 90 1.60 7.0 11.5 55.0 83.0 78.0 0.5 50 1.60 6.0 11.0 53.0 83.0 78.0 0.5 50 1.60 4.5 <9.9 52.0 80.0 <3.0 1.60 4.5 <12 40.045.0 40.045.0 84.0 82.0 <2.0 2.25 the barley is grown can also play a role in its flavor and aroma. Just as with grapes and hops, terroir matters for barley as well! Assortment: This is a measurement of the average size of each kernel of malt, as determined by the percentages of kernels which fall through a sieve with openings of a certain size. Practically, malt size gives you an idea of malt quality as well as the gap needed on your malt mill in order to get a proper crush. In ASBC testing, the listings for size indicate numbers mean the percentage of kernels which remain on a screen with 5/64 -in., 6/64 -in., or 7/64 -in. mesh and will be expressed in terms of “5/64 Max”. The EBC test is similar, except that a 2.2 mm mesh is used. In some cases, though, the size might just be listed as the percentage which is “plump” or “thin.” The term “Thru Max” is the maximum number of kernels which fall through the screen. As a rule of thumb, 6-row malt and more highly modified malts will also be a bit smaller, while 2-row malt will be a bit plumper. Typically, the plumper the kernels, the better the extract yield. Malt with more than 1% thin kernels (those which fall through a 5/64-in opening) or 2% less than 2.2 mm is likely to be undermodified or otherwise unsuitable for brewing. Equally important is uniformity of kernel size, since a large variation means a less uniform grain crush. Higher size variation between kernels can mean lower quality malt, although this isn’t usually a problem with modern malts. Regardless of plumpness, a lot of malt must have at least 90% adjacent sizes in order to crush reasonably well (i.e., about 90% must have be left on the 6/64 -in., and 7/64 -in. screens). H2O % Max: This row indicates the moisture percentage within the malt. It is also sometimes expressed as “Moisture content,” “% m.c.” or just MC. Moisture content on the malt is very important since, not only is it an indicator of quality, it also helps determine extract yield and storage stability of your malt. The lower the moisture content the better. Malt can have a moisture content of as low as 1.5% MC. Malts with higher moisture content are more prone to mold growth and lose more aroma and flavor during storage. No malt should have moisture content above 6% and colored malts shouldn’t have moisture content above 4% (except for caramel/crystal malts where 3.5-6% moisture content is acceptable although lower moisture is still better). British ale malts have the lowest moisture content, followed by Munich, Vienna, Pilsner, and lager malts. Caramel malts trap more water during drying, so they have slightly higher moisture content than other specialty malts. Malts with an excessively high level of moisture are said to be “slack” and are likely to have been poorly stored, dried or kilned. Moisture content also affects extract yield, since each percentage increase of moisture content results in an identical drop in potential extract yield. You can’t turn water into sugar! Color ASBC Deg. Lov.: This column indicates the malt’s color. Malt color is sometimes expressed as “degrees SRM,” “degrees Lovibond” or “degrees EBC” or just “°SRM,” “°L,” or “°EBC.” Not only is color a likely indicator of how a malt is likely to smell and taste in your beer, but it’s an indicator of how dark your beer is likely to be. While exact malt color isn’t so important for dark beers, it’s critical if you wish to make very light colored beers, such as Light Lagers or Pilsners. The color of a particular type of malt can vary widely from manufacturer to manufacturer and lot to lot. It’s particularly important to pay attention to malt color if you are switching between different brands of malt, since each maltings has its own color range. Differences in color are more pronounced at the dark end of the color range, with dark malts from the same maltings varying by up to 40° L from batch to batch! The color of U.S. and Canadian malts is expressed in terms of Standard Research Method (SRM) values or in degrees Lovibond. The color of European malts is usually measured in European Brewing Convention (EBC) units. A rough conversion between the different units: Degrees Lovibond = Degrees SRM Degrees EBC = (degrees L x 2.65) - 1.2 Degrees Lovibond = (Degrees EBC + 1.2)/2.65 Protein Max: This column is a measure of how much protein or nitrogen is in the malt and how much of that material can be dissolved in water. It indicates the maximum percentage of protein (or nitrogen) by weight. Protein percentage depends a great deal on the type of barley used to make the malt, but it can also be an indicator of its degree of modification and diastatic power. Indirectly, protein percentage can also be used to measure nitrogen percentage at a rate of 1% Nitrogen per 6.25% Protein. Highly diastatic American 6-row malts have the highest protein percentages (up to 13%), while European malts have slightly lower protein content (8-10%). North American malts are traditionally a bit higher in protein than their European equivalents. Malts with total protein values greater than 12% (1.9% Total Nitrogen) are more vulnerable to mash runoff and problems, protein haze and storage instability, unless adjuncts are used to reduce the total protein percentage of the grist. Likewise, when adjunct grains or sugars are used, malts of at least 10% protein are required to get appropriate levels of Free Amino Nitrogen (FAN) for yeast nutrition and to achieve proper head and body for all but the thinnest of beers. “Sol.” indicates the percentage of soluble proteins by weight. It is sometimes expressed as “Soluble protein” or “% SP.” Alternately, there might be a line for “Total Soluble Nitrogen,” or “% TSN,” instead, which indicates the total percentage of all soluble nitrogen in the malt. Regardless of the calculation uses, the soluble protein or total soluble nitrogen percentages are used to calculate the soluble nitrogen ratio. “Total” indicates total protein percentage by weight and can also be expressed as “Protein %” In some cases, the analysis sheet might also give a “total nitrogen” or “TN” percentage, or substitute that figure for the total protein percentage. Where total nitrogen is given, it indicates the percentage, by weight, or all nitrogenous matter in the malt, not just proteins. “S/T” [Soluble/Total] indicates the ratio of soluble protein to total protein as a percentage. This figure can also be described as “Soluble Nitrogen Ratio,” or “% SNR. Where Soluble Nitrogen and Total Nitrogen figures are given, Soluble Nitrogen/Total Nitrogen, SN/TN or Kolbach Index is listed instead. In all cases, this ratio is calculated by dividing soluble protein (or nitrogen) value by the percentage of total protein (or nitrogen) to get a ratio between the two. The soluble protein (or nitrogen) ratio is an important indicator of malt modification; the higher the number, the greater the degree of modification. Malts destined for infusion mashing, such as English pale malt should have an SNR of 36-42%, up to 45% for light-bodied beers. Beer made using just malt with 45% or higher SNR, will have a thinner body and poorer head due to lack of soluble nitrogen. For traditional lager malts, 30-33% indicates undermodification, while 3740% indicates overmodification. For a lot of malt with SNR than usual, the brewer must adapt by adding or modifying protein rests during mashing. Likewise, when dealing with a lot of malt with a lower than normal SNR, the brewer must shorten or eliminate protein rests. Extract Dry Min.: This column lists the minimum potential extract yield, as a percentage, at 0% moisture content. It is sometimes listed as Extract Yield. Even for homebrewers who don’t particularly care about consistency from batch to batch, Extract Yield percentages are of interest since it is an indicator of brewhouse efficiency - how much sugar you can wring out of your mash - which directly relates to wort gravity and the finished beer’s ABV. FG: This line indicates minimum extract yield, as a percentage. It is obtained by grinding a sample of malt into flour (0.2 mm average particle diameter), mashing the powder under laboratory conditions and then determining the amount of soluble materials (sugars, dextrins, starches and proteins) extracted. Since it is just a measure of maximum extract yield, the test ignores problems associated with a very fine grain crush, such as tannin extraction and mash runoff problems. FG is usually read side by side with the CG column. Taken on its own, it can be seen as an indicator of malt quality. The higher the extract percentage, the better the malt. More typically, FG is expressed as DBFG, also described as %DBFG or FGDB. This is an acronym meaning “Extract Yield - Dry Basis, Fine Grind.” A higher %DBFG indicates a malt with less protein and husk material and more soluble sugars and starches which can be extracted during mashing. Base malts should yield a minimum of 78% DBFG. CG: This line indicates minimum extract yield, as a percentage, using a coarser grain crush (0.7 mm average particle diameter), which is more like that obtained in brewery operations. More typically, CG is expressed as DBCG, %DBCG or CGDB. This is an acronym meaning “Extract Yield - Dry Basis, Coarse Grind.” It is used in conjunction with %DBFG to determine the degree of starch modification the grain experienced during the malting process. Unlike DBFG, the malt is crushed in a way which simulates a typical brewhouse malt crush, although actual brewhouse efficiency figures will be 5-15% lower than DBCG percentages. Even though CG figures are likely to be closer to actual brewhouse extract yields, they are still higher than “real world” yields. As a rule of thumb, actual brewhouse efficiency figures will be 5-15% lower. This is because, the malt has all its moisture removed before crushing begins, laboratory mashing equipment is more efficient than brewhouse mash tuns and the laboratory mash attempts to extract as much material as possible, ignoring potential problems with tannin extraction. The coarse-grind results are intended to demonstrate to the brewer the maximum that can be achieved using a crush that approximates that used by most breweries. F/C Diff. Max: This is a measurement of the maximum difference between Fine Grind and Coarse Grind extract yields, listed as a percentage and obtained by subtracting the coarse grind percentage from the fine grind percentage. It can also be expressed as just F/C or FG/CG. The difference between FG and CG percentages is another indicator of malt modification. An undermodified "steely," “glassy” or vitreous malt, which requires a protein rest, has a FG/CG difference of 1.8-2.2%. Well-modified, “mealy” malt suitable for infusion mashing will have a FG/CG difference of 0.5-1.0%. D.P. Min.: A measurement of Minimum Diastatic Power, sometimes just expressed as DP. North American maltings measure diastatic power in degrees Lintner. The terms IOB or .25 maltose equivalent are also sometimes used and are equivalent to degrees Lintner. European Other Ways of Measuring Extract Yield Malt suppliers can measure potential extract yields in a variety of ways other than FG/CG ratios. AICG: Also described as “CG, As Is,” this is an acronym meaning “As Is, Coarse Grind.” It is a measurement of coarse grind extract yield performed on malt with the listed moisture content, rather than malt where the moisture has been removed first. It gives more realistic, lower, estimates of extract yield. In other respects, it is identical to DBCG. AIFG: Also described as “FG, As Is,” this is an acronym meaning “As Is, Fine Grind.” It is almost identical to DBFG, but uses malt with the listed moisture content, rather than malt where the moisture has been removed first. Hot Water Extract (HWE): This is a measurement of extract yield used by British maltsters. It is a measure of how many liters of wort at S.G. 1.001 a kilogram of a malt will give at 68 °F (20 °C). It can also be listed as hot water extract, or L°/kg at 7M (malt ground to particles an average of 0.7 mm in diameter - a coarse grind) or L°/kg at 2M (malt ground to an average particle size of 0.2 mm in diameter - a fine grind). Divide by 386 to get DBCG or DBFG, respectively, expressed as a decimal. HWE for two-row lager or pale shouldn't be less than 300 at 2M, 295 at 7M. Cold Water Extract (CWE): This is a measurement of malt modification sometime used by British maltsters. It measures the amount of extract that is soluble in cold water. CWE percentage of 19-23% indicates a malt suitable for infusion mashing. DLFU: This is a measurement of FG/CG used by continental maltsters. It is identical to that measurement. Hartong (VZ 45°): This is a measurement of FG/CG sometimes used by continental maltsters. It is similar to CWE, but the water is held at a higher temperature (113°F/45° C) to allow for some enzyme action. The range of values is approximately double that of CWE. maltsters measure diastatic power in terms of °WK (Windisch-Kolbach units). DP °Lintner = (°WK + 16) / 3.5 DP °WK = (°Lintner x 3.5) -16 DP is a measurement of the malt’s ability to convert starch into fermentable sugars. Malts with a DP of 25-30 °Lintner will just convert their own starches, while those with higher values can convert excess starch into sugars, making them suitable for making beers which use adjunct grains. DP values range from 25-30 °Lintner for Munich, Vienna or lightly toasted malts, to 35-40 for English pale malt, ~100 for pale lager malt up to 125+ for “hot” American 6-row pale malt. Toasted, roasted or kilned malts have no diastatic power, so DP usually isn’t listed for them. Viscosity Max.: This is a measure of the breakdown of betaglucans during malting. It is often expressed as cP (centipoises units) or sometimes IOB. Malt with a high laboratory wort viscosity (over 1.75 CP) will need a beta-glucan rest to get the wort to run off easily during sparging. If viscosity is measured in IOB units, it should range between 6.3-6.8 at 158 °F [70 °C]. Other Malt Sheet Figures and Terms 1,000-Kernel Weight or Bushel Weight: The weight of a fixed volume of malt. This is an old measurement which gives a rough estimate of the plumpness or thinness of the malt kernels, as well as Using the Numbers Once you have obtained the numbers from your malt lot analysis, you can use them to adjust or design your recipe. AICG = DBCG/(1 + Moisture Content) - 0.002 Adjusted yield = AICG/brewhouse efficiency. Where brewhouse efficiency is expressed as a decimal instead of a percentage. Once you know brewhouse yield, you can predict the likely starting gravity (in SG or °Plato) per pound of malt in a gallon of water: SG per 1 lb. malt in 1 lb. water = Adjusted yield x 46.214 °Plato per 1 lb. malt in 1 lb. water = Adjusted yield x 11.486 Working backwards, you can determine brewhouse efficiency using the following formula: Brewhouse efficiency = ((SG x gal. of wort)/46.214)) / ((DBCG/(1 + moisture content) - 0.002) x lb. of malt Brewhouse efficiency = ((°P x gal. of wort)/11.486)) / ((DBCG/(1 + moisture content) - 0.002) x lb. of malt moisture content. An acceptable range for 1,000-kernel weight is 36-45 g, while 42-44 lbs. is acceptable for bushel weight. Alpha-Amylase or Dextrinizing Units (DU): Also sometimes described as Alpha Amylase Minimum. This measurement is similar to DP, but describes the malt’s ability to produce alpha amylase (which breaks down dextrins). Lager malts will have 35-50 DU, English pale malt has around 25 DU, while Munich/Vienna malt might have 10 or fewer DU. Conversion Time (minutes): Sometimes given instead of, or in addition to, diastatic power. European base malts should start to convert starches to sugars in less than 10 minutes, American base malts should start converting within 5 minutes. Degree of Clarity: Another estimate, based on ASBC standards, of the clarity of wort the malt will produce. "Normal" to "slightly hazy" are acceptable values. Degree of Crystallization: This measurement is only used for specialty malts which are supposed to have a vitreous texture, such as crystal malt. Caramel malts should have a degree of crystallization above 85%, while crystal malts should have a score of 95% or higher. DMS precursor (DMS-P): This is a measure of the levels of Smethyl methionine (SMM) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in the malt, which are converted to dimethyl sulfide (DMS) when the wort is heated. These compounds are generally present in higher quantities (5-15 ppm) in continental lager malts, less for ale malts. The greater the degree of modification, the lower the DMS-P levels. Friability: This is a measure of the malt’s likelihood of crumbling when crushed. It is similar to mealiness and is sometimes substituted for that test. Any malt should be at least 80% friable, while those used for infusion mashing should be at least 85% friable. Growth: Also described as Acrospire Growth. This is another traditional method of assessing the degree to which malt has been modified. Acrospire growth is expressed in ranges 0-1/4, 1/4-1/2, 1/2-3/4, 3/4-full, or overgrown (measured in length of acrospires to length of the barley kernel). The longer the acrospires, the more modified the malt. American maltsters typically let the acrospire grow to ¾ length, while the acrospires is allowed to grow ¾ to the entire length of the kernel for English pale malts. By contrast, traditional German lager malts only allowed the acrospire grow to ½ to ¾ the length of the kernel. Mealiness (%): The texture of a malt kernel’s endosperm can be described as “mealy” “"half-glassy/glassy-ends" (AKA “hard ends”) or "glassy" (AKA “vitreous” or “steely”) depending on degree of modification during mashing. Mealiness measures the percentage of kernels in a sample which are classified as mealy (i.e., no more than 25% of the endosperm is “glassy”). Kernels are “half-glassy”/”glassy ends” if the endosperm is 25-75% glassy. Kernels where the endosperm is over 75% glassy are described as being “glassy,” “vitreous,” or “steely.” Mealiness is another measure of malt conversion and is also a useful measurement of how well the malt will crush. Since mealy endosperm is more permeable by water, it is also more accessible to starch conversion enzymes, so mealiness is an indirect indicator of extract yield. A higher degree of modification during malting results in more mealy malt kernels. Less modified malts have more a steelier texture and give less extract. Any base malt should be at least 90% mealy, while malts intended for infusion mashing must be at least 95% mealy. Where mealiness/half-glassy/glassy is expressed as a ratio, the percentage should be at least 92%/7%/1% for decoction or step mashing, and 95%/4%/1% or better for infusion mashing. Odor of Mash: This is a one or two word description of how the mash smells, based on ASBC standards. Often there will be no listing, or a listing of “normal.” “Aro” or “aromatic” indicates a greater than normal aroma while “V. Aro” or “very aromatic” means a much higher than normal aroma. Other descriptors include “bread," “crackers” and “burnt coffee.” Speed of Filtration: An estimate, based on ASBC standards, of the levels of beta-glucans in the malt, as well as the degree of starch and protein conversion. It can be used as an estimate of the speed of runoff during sparging. Vitreosity: This is the opposite of mealiness. It is a measurement of the average level of “glassiness” of the endosperms in a sample of malt kernels. It is measured by taking a set number of malt grains, slicing them open and examining the endosperm. A score of 1 is assigned to kernels with glassy endosperms; 0.5 to half-glassy kernels; 0.25 to those with glassy ends; and 0 to mealy kernels. The sum is totaled and averaged, with a vitreosity of 0-0.25 preferred. Due to the unreliability of this test (it depends on subjective observations of vitreosity) it is seldom listed. Beer Defect: Tannins Description: Tannins refer to a broad class of polyphenols which have molecular weights of 500-3,000. They are naturally present in many plant materials, such as tea, coffee, peat moss, tree fruits and grapes (in the skins, pits and seeds), oak, hops and barley. When oxidized, they impart a harsh bitterness, drying mouthfeel and reddish color to beer. In certain cases, tannins can combine with high molecular weight proteins to form chill (protein) haze. The German term for tannin astringency is “Herbstoffe” and astringency or tannin character is considered to be a defect in German style beers. A feature of German dark lagers is the use of dehusked dark malt to get dark grain colors and flavors without imparting husky notes. Dehusked dark malt also gives beers such as Baltic Porter and “India Dark Ale”/Black IPA their distinctive malt character. In barley kernels, tannins are found mostly in the husk, but also exist in the pericarp and the aleurone layer. Tannins are also present in hops. In a typical wort, 2/3 of tannins present are from the malt, while the other third come from hops. While tannins help precipitate both hot break and cold break, excessive levels, especially excessive levels of malt-derived tannins have unwanted effects on appearance, flavor and mouthfeel. How Are Tannins Perceived?: Polyphenols are detectable in aroma, flavor and mouthfeel, and might also alter a beer’s appearance. Appearance: Tannins can impart a reddish color to beer (seen in beers such as Flanders red ale). In some cases, they can interact with proteins naturally found in the malt to cause chill (protein) haze. Aroma and Flavor: Variously described as harshly bitter, husky, oaky or tea-like. In some cases, their flavor is described as vinous, reminiscent of red wine or unripe fruit, metallic, chalky or dusty. They typically impart a harsh, lingering, unpleasant bitterness, as compared to mellower, less lingering, more pleasant hop bitterness imparted by alpha acids. Due to the comparatively large size of most polyphenols molecules, they aren’t particularly volatile and are easier to detect in flavor than aroma. Also, keep in mind that flavor and mouthfeel effects play off of each other. Aspects of polyphenolic “flavor” are actually elements of mouthfeel. Mouthfeel: In beer tasting, mouthfeel is used to describe the physical characteristics of the beer as it interacts with the tissues of your mouth, such as viscosity, carbonation, and so forth. Polyphenols truly affect mouthfeel because they’re astringents - they chemically react with proteins and extract water from tissues. For this reason, tannins are used to tan hides for leather. So, when polyphenols contact your taste buds, tongue or inside of your mouth, they actually start to “tan your hide” from the inside out! You perceive this sensation as a drying, puckering or astringent sensation, or occasionally as a dusty texture in the mouth. When Are Tannins/Astringency appropriate? Low levels of tannins are acceptable, even expected, in wood-aged beers, including styles such as Flanders Red Ale. For most styles of beer, however, tannins are inappropriate. Origins of Tannins in Beer Excessive levels of tannins can get into your beer due to bad technique at virtually each step of the brewing process. Grain Crush: An excessively fine grind, or a high proportion of flour from your crush, aids in extracting polyphenols from husks. Also, very fine particles of husk material can be run off with the wort where they can release even more tannins during the wort boil. This is one of the most common causes of astringency. Cures: Crush your grain properly. Make sure that the grain husks are mostly intact rather than being shredded or ground to flour. An ideal grain crush will leave the husks virtually intact while pulverizing the material inside the husk. Mashing/Steeping: Tannins can be extracted from malt husks during malting or steeping. Bad process during this step is also a big source of astringency. The three ways that tannins can get into your beer during mashing/steeping are: 1) Strike water, steeping, or mashing out temperature too high. Above about 170 °F, tannins are extracted from grain husks. 2) Excessively long mashing times. Very long contact with water can extract tannins from husks. 3) Improper wort pH: Tannins are slightly acidic, so alkaline mash conditions help to extract tannins. Cures: Keep strike water and mash temperature during mash out below 170 °F. Keep mash pH within proper ranges (5.2-5.6 pH). Treat mash water to avoid excessive alkalinity. Add dark/specialty grains towards the end of mashing in order to minimize tannin extraction, since they don’t need to undergo starch conversion. Sparging: Excessive sparging and sparging with hot and/or alkaline water can also extract tannins from grain husks. Bits of husk can also be carried into the wort during runoff and sparging. Cures: Keep sparge water between 5.2 and 5.6 pH and below 170 °F. Stop sparging once the SG of the runoff falls to about 1.010. Recirculate or filter your runoff until it runs clear. Wort Boil: Tannins are extracted from plant materials during boiling, but paradoxically, a good wort boil also helps to solve hazing and instability issues associated with polyphenols, since they bind with proteins to form the hot break and cold break. High levels of hops, especially bittering hops boiled for long periods of time, can also impart unwanted polyphenols. Partial grain brewers can often get polyphenols in their beer during wort boil if they steep specialty grains in their wort kettle. Brewers who add huge quantities of hops to their brew can also impart unwanted polyphenols. Cures: Don’t let any material which might impart unwanted levels of polyphenols into your wort: grain husks, whole fruits, excessive levels of hops. If you steep your grains in your wort kettle, use a grain bag so that you get all of your grains out of the kettle before you start boiling. Never let your steeping grains get above 169 °F. Don’t steep your grains for prolonged periods (more than 45 minutes or so). Use smaller amounts of high alpha hops for bittering rather than larger quantities of low-alpha hops. Get a vigorous rolling boil of at least 1 hour to aid hot break formation, but limit total boil time to no more than two hours after you’ve added your hops (you get maximum alpha acid extraction after 2 hours). Use kettle finings (e.g., Irish moss) to promote hot break. Wort Cooling and Fermentation: Polyphenols can cause chill haze and astringency if cold break or trub is carried into the cooled wort. The scummy brown material which appears on the top of fermenting wort, and the trub which falls out of solution, also contains a high concentration of polyphenols. If you are not careful, it can get into the finished beer. Cure: Filter or whirlpool wort to leave most of the hot and cold break behind (but you’ll want to let a bit into your beer to aid yeast development). Use blow off fermentation along with adequate head space, to help get trub out of your beer - it should end up in the blowoff container or on the sides of your container rather than in your beer. When you rack your beer, be careful to disturb the sediment as little as possible. Try to get as little trub as possible when you rack. Conditioning/Dry Hopping: Excessive hop levels or excessive dry hopping times can extract polyphenols from the hops. During conditioning, polyphenols levels can be reduced by fining, cold conditioning or aging. To a much lesser extent, leaving your beer on the trub for extended periods of time can also allow polyphenols to get into your beer. Cures: Don’t let your beer sit on the lees in primary for long periods of time (i.e., more than a month or so). Limit dry hopping time. Use a hop bag or equivalent to help get hop material out of the beer. If necessary, fill your bag with marbles to get it to sink. You can sanitize both the bag and the marbles before you add it to your beer. If your beer suffers from chill haze or astringency, polyphenols levels can be reduced using either or both PVPP (polyvinylpyrrolidone - trade named Polyclar) or brewer’s gelatin as fining agents. Both act by encouraging polyphenols to precipitate. They also have the effect of slightly reducing polyphenolic browning, which slightly lightens the beer’s color. Cold conditioning or lagering the beer has a similar effect on precipitating polyphenols, but doesn’t have the lightening effect. Aging beer also allows polyphenols to settle out of solution. Other Sources of Polyphenols Optional steps during the brewing process can introduce polyphenols into your beer, as can improper sanitizing and cleaning technique. Bacteria: Some bacteria can produce polyphenols or promote polyphenol production. Typically, though, these bugs also cause much more serious off-flavors such as acetic, lactic or phenolic flavors and aromas, making a slight astringency the least of your worries. Cures: Use proper cleaning and sanitizing procedures for your equipment. Make sure that your wort isn’t exposed to the open air. Don’t siphon beer using your mouth. Barrel Aging: Prolonged contact with wood, especially certain varieties of oak, can extract polyphenols from the wood. Over time however, these compounds get oxidized into other materials or are precipitated out of solution. Cures: Limit contact of beer with wood. Be aware that smaller and newer barrels will impart more wood character than older and larger barrels. When making a small batch of wood-aged beer, it is generally better to use wood chips or wood slats rather than actually aging your beer in a wooden barrel. Extended aging time will reduce and mellow tannins extracted from wood. Fruit: Almost all fruits, especially fruits with thick husks, such as apples, bananas, cranberries, wine grapes and pomegranates contain tannins. When making fruit beer, you must be careful not to inadvertently extract tannins. Cures: Avoid using parts of the fruit which are high in tannins (i.e., skins, pits, stems, husks and cores). Keep pasteurization temperatures below 170 °F. Don’t add whole fruits to boiling wort. Avoid prolonged contact of whole fruit and fermenting wort (unless the style demands it e.g., a fruit lambic). Herbs and Spices: Herbs and spices, being plant materials, are often potent phenol producers. A common side effect of adding herbs or spices to your favorite beer is increased dryness due to polyphenols, especially if you boil the materials or allow them to remain in contact with your beer for long periods of time. Cures: Never boil herbs or spices, including materials such as coffee or chocolate. Instead, steep them in water of no more than 170 °F or extract their essential oils by soaking them in vodka or grain-neutral spirits and adding the mixture to your beer in secondary. If you can’t extract the essences and must add them directly to your beer, put them in a bag so that you can get all of the herbs or spices out of your beer. To get the bag to sink, you can load it with glass marbles, which you can easily sanitize along with the bag before you add your herbs or spices. BJCP Category 4 - Dark Lagers This category covers dark (brown to black) bottom-fermented beers. While this category is mostly focused on German and German style beers, it includes “Dark American Lagers” - this is actually something of a catchall category for any table-strength dark lager which doesn’t fit into any other category. History: German Dark lagers are descended from two old brewing traditions. The first tradition is that of pre-modern brewing, when all malt was brown or amber malt and all beer was brown or dark brown and possibly quite cloudy. The second tradition is that of British Porter/Stout brewing. In the late 18th century, due to the worldwide popularity of English porters, Continental brewers began brewing lager versions of English porters and stouts. While English-style brown beers never became as popular in Europe as they were in England and the British Empire (most continental porters died out by the mid-19th century), some brands survived. Schwarzbier (Black Beer) is a regional specialty from southern Thüringen in northern Franconia (part of the principality of Bavaria), particularly around the towns of Kulmbach and Bamberg. This style of beer is related to the brown and black smoked beers (rauchbiers) for which the region is famous, as well as more obscure styles of beer such as Kellerbier and Zoiglebier (both cloudy, traditionally brown farmhouse ales). A beer similar to Schwarzbier is found in Bad Köstritz near Leipzig. It has a mellower malt profile than Franconian schwarzbier, since it uses de-bittered roast malt, like that used to produce Baltic porters. Munich Dunkel is possibly a remnant of medieval and Renaissance brewing traditions, a surviving form of continental porter, or both. It is slightly stronger than Schwarzbier, but slightly less hoppy and has a different flavor profile. Rather than being black, Munich Dunkels are a mahogany brown. Dark American Lager is a simplified version of German dark lager, adapted to American (or industrial brewing) ingredients and tastes. They are less complex in both hop and malt flavor than their German counterparts, and are a bit thinner in body, making them easier to drink. Note that Dark American Lager is something of a catchall category, and many of the best examples are not brewed in America! Some U.S. beers in this category are merely light or amber lagers with caramel coloring added; essentially “industrial lagers dressed in black.” These represent typical products of large international or regional breweries. Other examples, such as Shiner Bock, might represent historical U.S. or Mexican traditions of dark lager beer brewing, using German brewing techniques adapted to use local ingredients and to appeal to local consumer tastes. Finally, there are American craft-brewed dark lagers which don’t fit into any other category, such as Dixie Blackened Voodoo Lager. European examples represent various dark lagers which might, or might not, be inspired by American interpretations of German dark beers. They include more adjunct heavy, lower alcohol variants of bottom-fermented Baltic porter, as well as all-malt dark or brown generic “Euro lagers” which don’t fit into the Schwarzbier or Munich Dunkel styles. A beer possibly related to a Baltic porter is Baltika #4, while examples such as Beck’s Dark or Warsteiner Dunkel represent “euro dark lagers.” Brewing Dark Lagers: German dark lagers are brewed using Vienna or Munich malt as a base. Munich Dunkels add a bit of chocolate and crystal malt, while Schwarzbiers add a bit of Pilsner and Carafa malts. Both styles are decoction mashed, are hopped with noble hops and fermented using Munich lager yeast. Industrial dark American lagers are brewed much like American Standard or Premium Lagers; except for a bit of caramel coloring or chocolate malt added o darken color. They use small amounts of noble or noble-derived hops and are fermented using American lager yeast. European and craft brewed versions might have more complex grist and hop bills. Some are made with a certain amount of sugar instead of adjunct grains. Other Dark Lagers: Don’t assume that the BJCP Guidelines cover every style of Dark Lager! There are entire families of dark lager beers brewed in the Austria, Czech Republic, Switzerland and elsewhere which aren’t represented in the style guidelines. These can be stronger or lighter, drier or sweeter, thinner or fuller bodied, darker and/or hoppier than the listed styles and might have different malt and/or hop character. Also, rather than covering the continuum of dark lager styles from weakest to strongest, the BJCP Guidelines split dark lagers up between three categories: Dark Lagers (Category 4), Bocks (Category 5) and Porter (Category 12). If you are entering a strong dark lager into competition, it might be judged more favorably as a Traditional Bock (5B), Doppelbock (5C) or a Baltic Porter (12C). Dark lagers which are probably best entered as specialty beers (Category 23) include: Austrian Dunkel/Doppelmalz: Based on Munich Dunkel or Schwarzbier, but brewed to 13° Plato and attenuated to only 4.5% ABV, meaning that they’re much fuller in body and can be extremely sweet. Similar beers are, or were, brewed in Switzerland. Czech 8° or 10° Dark Lagers (AKA Tmavé/Černé Výčepní Pivo, literally, “Dark/Black Draught Beer”): Sweet and malty or dry and roasty low alcohol (3-4% ABV) dark lagers. Some have moderate noble hop flavor and aroma (usually Saaz hops). Czech 11-12° Dark Lagers (AKA Tmavý/Černý Ležák Pivo, literally “Dark/Black Lager Beer”): This is a broad class of dark lagers, some of which fall into the category of dark American lager, Munich dunkel or schwarzbier. Malt character ranges from quite sweet to quite dry, sometimes with dark grain character like a conventional porter or stout. Color ranges from light brown to black. Some can have moderate noble hop flavor and aroma (usually Saaz hops). ABV ranges from 4.4 - 5%. They are typically lagered for 2-3 months before packaging. Czech 13-14° Dark Lagers (AKA Tmavé/Černé Speciální Pivo literally “Dark/Black Specialty Beer”): Basically, an “export” strength version of the Czech 11-12° dark lagers. They are often inspired by Munich dunkels or schwarzbiers and are mostly produced by Czech artisan brewers. They are usually full-bodied and malty, but have a high degree of hop bitterness, again, usually from Saaz hops. They range from 5.3-5.8% ABV. The best known example is U Fleků Ležák. Czech 15-17° Dark Lagers (AKA Tmavé/Černé Speciální Pivo): Stronger versions of the above at 6 - 7% ABV. Basically, dark bock or doppelbock beers, albeit with a different malt and hop character. Czech 18-24° Dark Lagers (AKA Tmavé/Černé Speciální Pivo): Even stronger versions of the above at 8 - 10% ABV. Basically, dark doppelbocks, but some can be even stronger than traditional German doppelbocks. Similar to these are some traditional, now rare or extinct, Austrian and Swiss beers. Czech Porter: Bottom-fermented, very full-bodied with lots of dark malt character and moderate to high hop bitterness. Possibly local interpretations of the Deutsche porter or Baltic porter styles. Before World War 2, this represented a top-end product for Czechoslovakian breweries. It is now quite rare. Deutsche Porter: This is a historical 18th or 19th century style which is nearly extinct in Germany. It has recently been revived by a few German microbrewers and brewpubs. It seems to be a bottom-fermented robust porter (BJCP substyle 12A) or brown porter (BJCP substyle 12B) of 4.5-5.5% ABV. Alternately, it might be a lower alcohol, drier interpretation of Baltic porter (BJCP substyle 12C) or a bottom-fermented version of dry stout (BJCP substyle 13A) or sweet stout (BJCP substyle 13B). Eastern European Dark Lagers: There are Polish, Baltic and Russian dark lagers which are different from either Czech or German examples. They might be weaker, more adjunct-laden versions of Baltic porter or local interpretations of German or Czech beer styles. Many fall into the category of dark American lager. They are usually full-bodied and sweet with low but detectable levels of hop bitterness. Dark grain character is usually quite subdued. Latin American Dark Beers (AKA Malta): This category covers a wide range of brown to black Mexican and South American beers which roughly fall into the dark American lager style. Some can be quite sweet and full-bodied, while others are drier and have relatively thin body. All have very little dark grain or hop character. Note that the term Malta can also apply to a non-alcoholic malt-based soft drink which is popular in the Caribbean. 4A. Dark American Lager Aroma: Little to no malt aroma. Medium-low to no roast and caramel malt aroma. Hop aroma may range from none to light spicy or floral hop presence. Can have low levels of yeast character (green apples, DMS, or fruitiness). No diacetyl. Appearance: Deep amber to dark brown with bright clarity and ruby highlights. Foam stand may not be long lasting, and is usually light tan in color. Flavor: Moderately crisp with some low to moderate levels of sweetness. Medium-low to no caramel and/or roasted malt flavors (and may include hints of coffee, molasses or cocoa). Hop flavor ranges from none to low levels. Hop bitterness at low to medium levels. No diacetyl. May have a very light fruitiness. Burnt or moderately strong roasted malt flavors are a defect. Mouthfeel: Light to somewhat medium body. Smooth, although a highly-carbonated beer. Overall Impression: A somewhat sweeter version of standard/premium lager with a little more body and flavor. Comments: A broad range of international lagers that are darker than pale, and not assertively bitter and/or roasted. Ingredients: Two- or six-row barley, corn or rice as adjuncts. Light use of caramel and darker malts. Commercial versions may use coloring agents. Commercial Examples: Dixie Blackened Voodoo, Baltika #4, Warsteiner Dunkel. 4B. Munich Dunkel Aroma: Rich, Munich malt sweetness, like bread crusts (and sometimes toast.) Hints of chocolate, nuts, caramel, and/or toffee are also acceptable. No fruity esters or diacetyl should be detected, but a slight noble hop aroma is acceptable. Appearance: Deep copper to dark brown, often with a red or garnet tint. Creamy, light to medium tan head. Usually clear, although murky unfiltered versions exist. Flavor: Dominated by the rich and complex flavor of Munich malt, usually with melanoidins reminiscent of bread crusts. The taste can be moderately sweet, although it should not be overwhelming or cloying. Mild caramel, chocolate, toast or nuttiness may be present. Burnt or bitter flavors from roasted malts are inappropriate, as are pronounced caramel flavors from crystal malt. Hop bitterness is moderately low but perceptible, with the balance tipped firmly towards maltiness. Noble hop flavor is low to none. Aftertaste remains malty, although the hop bitterness may become more apparent in the medium-dry finish. Clean lager character with no fruity esters or diacetyl. Mouthfeel: Medium to medium-full body, providing a firm and dextrinous mouthfeel without being heavy or cloying. Moderate carbonation. May have a light astringency and a slight alcohol warming. Overall Impression: Characterized by depth and complexity of Munich malt and the accompanying melanoidins. Rich Munich flavors, but not as intense as a bock or as roasted as a schwarzbier. History: The classic brown lager style of Munich which developed as a darker, malt-accented beer in part because of the moderately carbonate water. While originating in Munich, the style has become very popular throughout Bavaria (especially Franconia). Comments: Unfiltered versions from Germany can taste like liquid bread, with a yeasty, earthy richness not found in exported filtered dunkels. Ingredients: Grist is traditionally made up of German Munich malt (up to 100% in some cases) with the remainder German Pilsner malt. Small amounts of crystal malt can add dextrins and color but should not introduce excessive residual sweetness. Slight additions of roasted malts (such as Carafa or chocolate) may be used to improve color but should not add strong flavors. Noble German hop varieties and German lager yeast strains should be used. Moderately carbonate water. Often decoction mashed (up to a triple decoction) to enhance the malt flavors and create the depth of color. Commercial Examples: Paulaner Alt Münchner Dunkel, Hofbräu Dunkel. 4C. Schwarzbier (Black Beer) Aroma: Low to moderate malt, with low aromatic sweetness and/or hints of roast malt often apparent. The malt can be clean and neutral or rich and Munich-like, and may have a hint of caramel. The roast can be coffee-like but should never be burnt. A low noble hop aroma is optional. Clean lager yeast character (light sulfur possible) with no fruity esters or diacetyl. Appearance: Medium to very dark brown in color, often with deep ruby to garnet highlights, yet almost never truly black. Very clear. Large, persistent, tan-colored head. Flavor: Light to moderate malt flavor, which can have a clean, neutral character to a rich, sweet, Munich-like intensity. Light to moderate roasted malt flavors can give a bitter-chocolate palate that lasts into the finish, but which are never burnt. Medium-low to medium bitterness, which can last into the finish. Light to moderate noble hop flavor. Clean lager character with no fruity esters or diacetyl. Aftertaste tends to dry out slowly and linger, featuring hop bitterness with a complementary but subtle roastiness in the background. Some residual sweetness is acceptable but not required. Mouthfeel: Medium-light to medium body. Moderate to moderately high carbonation. Smooth. No harshness or astringency, despite the use of dark, roasted malts. Overall Impression: A dark German lager that balances roasted yet smooth malt flavors with moderate hop bitterness. History: A regional specialty from southern Thüringen and northern Franconia in Germany, and probably a variant of the Munich Dunkel style. Comments: In comparison with a Munich Dunkel, usually darker in color, drier on the palate and with a noticeable (but not high) roasted malt edge to balance the malt base. While sometimes called a “black pils,” the beer is rarely that dark; don’t expect strongly roasted, porter-like flavors. Ingredients: German Munich malt and Pilsner malts for the base, supplemented by a small amount of roasted malts (such as Carafa) for the dark color and subtle roast flavors. Noble-type German hop varieties and clean German lager yeasts are preferred. Commercial Examples: Köstritzer Schwarzbier, Kulmbacher Mönchshof Premium Schwarzbier, Samuel Adams Black Lager, Gordon Biersch Schwarzbier. Vital Statistics Style 4A. Dark American Lager 4B. Munich Dunkel 4C. Schwarzbier (Black Beer) O.G. 1.044-1.056 1.048-1.056 1.046-1.052 Sub-Style Comparison Table Differences 4A. Dark American Lager Aroma: Malt aroma usually more subdued, less complex. Can have low levels of yeast character (DMS, acetaldehyde, diacetyl, esters). Appearance: Lightest color (dark amber to medium brown), lower, less-persistent head. Flavor: Lighter, less complex malt character. Low-medium sweetness. Very low-medium low hop bitterness. Some DMS, esters acceptable. Mouthfeel: Thin-medium thin body. Highly carbonated. Overall: Highest alcohol (up to 6% ABV), lowest IBU (8-22), lowest FG (1.008-1.012), lightest color (8-20 SRM). Can use adjuncts or coloring agents. 4B. Munich Dunkel Aroma: Rich, complex bready Munich malt. No yeast character. Appearance: Unfiltered hazy versions OK. Flavor: Rich, complex bready Munich malt. Can be somewhat sweet. No harsh roasted or sweet caramel malt notes. Hop bitterness detectable, but low. Clean yeast character. Mouthfeel: Medium to medium-full body. Light astringency OK. Slight alcohol warmth OK. Overall: Not as strong as a bock or as roasted as a schwarzbier. Roastier and darker than a Märzen. Mostly uses Munich malt. 4C. Schwarzbier Aroma: Low-medium malt aroma, can be clean and neutral or rich and Munich-like. No burnt notes. Low DMS OK. Appearance: Darkest color (brown to dark brown). Never black. Large persistent head. Flavor: Low-medium malt flavor, can be clean and neutral or rich and Munich-like. No burnt notes. Medium-low to medium hop bitterness. Clean yeast character. Dry, lingering finish. Mouthfeel: Medium-light to medium body. Medium to medium high carbonation. No astringency. Overall: Darkest color (17-30 SRM), highest IBU (17-32). Darker, drier and slightly roastier than Munich Dunkel Similarities Aroma: No to low noble hop aroma. Can have caramel & roast malt notes. No-low yeast character. Appearance: Usually clear. Ruby highlights, tan head. Flavor: Generally restrained dark malt character. Not excessively sweet. No to low noble hop flavor. Generally clean yeast character. Mouthfeel: Medium to high carbonation. F.G. 1.008-1.012 1.010-1.016 1.010-1.014 ABV 4.2-6% 4.5-5.6% 4.4-5.4% IBU 8-20 18-28 22-32 SRM 14-22 14-28 17-30+ Inspirational Reading Books & Magazines Daniels, Ray. Designing Great Beers, Brewer’s Publications, Boulder, Co. Fix, George. Principles of Brewing Science, Brewer’s Publications, Boulder, Co. Mosher, Randy. Radical Brewing, Brewer’s Publications, Boulder, Co. Noonan, Greg. New Brewing Lager Beer, Brewer’s Publications, Boulder, Co. Palmer, John. How to Brew, Brewer’s Publications, Boulder, Co. Snyder, Stephen. The Brewmaster’s Bible, Harper-Collins Press, New York, NY. Zainasheff, Jamil & Palmer, John, Brewing Classic Styles, Brewer's Publications, Boulder, Co. Zymurgy, Jan/Feb, 2008, p. 15. Crafting Dark Lagers, Amahl Turczyn Scheppach. Web Sites Understanding Malt Analysis Sheets Understanding Malt Analysis Sheets -How to Become Fluent in Malt Analysis Interpretation (http://www.brewingtechniques.com/bmg/noonan.html) Understanding Malt Spec Sheets: Advanced Brewing (http://www.byo.com/stories/article/indices/34-grains/1576-understanding-malt-specsheets-advanced-brewing) Acronyms and Abbreviations Used in Beer & Brewing Discussions (http://kotmf.com/articles/acronyms.php) Malt Analysis Sheets, etc. Lot Analysis Program (http://www.specialtymalts.com/tech_center/lot_analysis.html) Typical Analysis (http://www.brewingwithbriess.com/Assets/PDFs/Briess_MaltTypical%20Analysis.pdf) Know Your 2010 Malting Barley Varieties (http://www.ambainc.org/media/AMBA_PDFs/Pubs/KYMBV_2010.pdf) Tannins Tannin Chemistry (http://www.users.muohio.edu/hagermae/tannin.pdf) Tannins (http://www.bacchus-barleycorn.com/catalog/article_info.php?articles_id=28) Dark Lagers Blackened Voodoo Lager (http://www.brewery.org/gambmug/recs/305.shtml) (recipe) Dunkel (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunkel) Dunkel (http://www.germanbeerinstitute.com/Dunkel.html) Dunkel - The first beer-purity-law lager (http://www.realbeer.com/library/authors/dornbusch-h/dunkel.php) Schwarzbier (http://www.germanbeerinstitute.com/Schwarzbier.html) Schwarzbier (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schwarzbier) Schwarzbier (http://byo.com/component/resource/article/Recipes/100-European%20Dark%20Lager/1379-schwartzbier) (Recipe) Schwarzbier - The 'stout' of lagers (http://www.realbeer.com/library/authors/dornbusch-h/schwarz.php) Shiner Bock recipe (http://skotrat.com/skotrat/recipes/lager/bock/recipes/2.html) (recipe) The 10 Hardest Beer Styles (http://byo.com/component/resource/article/Indices/11-Beer%20Styles/1492-the-10-hardest-beer-styles) European Beer Guide (http://www.europeanbeerguide.net/)