BaFin

advertisement

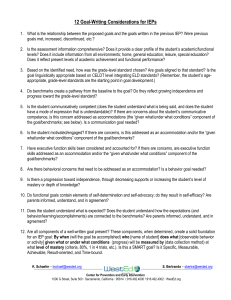

Seite 1 | 8 Consultation on a Possible Framework for the Regulation of the Production and Use of Indices serving as Benchmarks in Financial and other Contracts Answers of the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin (Germany)) Chapter 1. Indices and Benchmarks: What they are, who produces them and for which purposes 1. As a financial regulatory authority, BaFin does not produce benchmarks. We also do not contribute data. 2. BaFin uses benchmarks rather indirectly in the supervisory practice. For example BaFin staff analyzing potential market abuse or insider trading uses benchmarks for examining the market impact of (corporate) news. Also the research department uses benchmarks when monitoring macroeconomic risks. Benchmarks may be also a source when analyzing investment fund performances. 3. No. 4. Products that are supervised by BaFin and which are referenced to indices are index-tracking investment funds (mainly Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs)) and securities (notes/certificates) publicly offered. There are 105 index-tracking ETF authorized in Germany. The market volume is about 31 bn. Euro. Securities referenced to indices (non-interest benchmarks) are about 180,000 with a market volume of about 21 bn. Euro. 5. See above. 6. There are various benchmarks used in our jurisdiction based on transaction data, panel submission etc. For examples see answer to question 8. Regulatory requirements to the basement of benchmarks apply only with regard to investment funds tracking indices. For a full description of the index requirements, see art. 9 and 12 Directive 2007/16/EC and the provisions set out in the recently published ESMA Guidelines on ETF and other UCITS issues. Relevant provisions are, e.g., that they are constructed with sound procedures to collect prices, including pricing procedures for components where a market price is not available and that the methodology is fully transparent. 7. Most important factors would be: • A robust, fully transparent and understandable methodology for calculation; Seite 2 | 8 • Credible governance structures; Adequate controls must be in place; adequate processes for identifying, avoiding and, if this is not possible, managing conflict of interest • An appropriate degree of formal oversight and regulation (e.g. registration of certain benchmark providers) • The use of transaction data to the extent possible • Transparency and openness; calculation methodology and (types) of data should be freely available An example for a benchmark fulfilling these criteria would be the DAX-30 index. Chapter 2. Calculation of Benchmarks: Governance and Transparency. 8. In the following the most important benchmarks in economic terms for the German financial markets are covered. The equity indices of DAX and Eurostoxx, the sovereign bond indices of REX, settlement prices at the Eurex exchange and the interest reference rate EONIA (European OverNight Index Average) are all based on actual transactions in the underlying market. Foreign Exchange Reference Rates by the ECB are based on a regular daily concertation procedure between central banks across Europe and worldwide. CDS-spreads of single-names and indices (e.g. iTraxx) sponsored by Markit are based on quotes by contributors (e.g. market-makers). The interest reference rates EURIBOR and LIBOR are based on submitted estimates for unsecured borrowing costs by contributing banks. 9. No. There may only be an advantage when no reliable actual data exist (e.g. no relevant trading or illiquid markets). Then estimates based on statistical methods could be useful. 10. Using transaction data would reduce the vulnerability of benchmarks. Only in cases where no transaction data exist but the price information is deemed indispensable in order that the benchmark represents the market adequately, estimated or modelled prices by using statistical techniques could be a solution which would lead to a mixture of transaction and estimated data. In any case, the fact that data are “model based” as well as the pricing procedures would need to be disclosed. 11. The benefits are the reduction of vulnerability. But also generally, the goal of a benchmark is to adequately represent the market to which it refers, which would be best achieved by using actual and reliable transaction data. Hence, the use of transaction data Seite 3 | 8 would improve the economic quality of the benchmark since it would better represent ma ket activities. 12. Banks which submit quotes to the calculation of Benchmarks should do so in accordance with certain rules of conduct. With regard to those German banks which submit quotations for LIBOR and EURIBOR, BaFin has drawn up a catalogue of principles, which banks in the future have to adhere to: • Four eyes principle as regards the verification of quotes, which should ensure that conflicts of interest are avoided • Detailed documentation, which should include the grounds for a quotation (e.g. actual transactions) • Clearly formulated procedures and clear personal responsibilities • Regular review by a unit, which is not involved in the quotations process (e.g. compliance), and regular internal audits • Reporting to senior management if irregularities are identified by compliance or internal audit These principles established for banks may serve as a blueprint for bechmark (and benchmark data) providers outside the current regulatory scope. Specifically, private sector providers of benchmarks, that are relevant for financial instruments in regulated markets, shall be obliged to register with the competent regulatory authority. The details and terms of reference benchmarks should be disclosed, e.g. in a prospectus. 13. Self-regulation alone, e.g. through a code of conduct, cannot ensure the integrity of the submission process. The basic principles of a proper business organization, which should also apply to the submission process, need to be defined in statutory regulation. The function of a code of conduct could be to spell out these principles in more detail in the context of a specific benchmark. 14. Contributions to the calculation of benchmarks should be subject to the same rules of conduct as any other business activity which banks undertake. At least in German law it is not necessary to explicitly make the submission of quotes a regulated activity. The submission of inaccurate quotes could be sanctioned under a market abuse regime. Depending on the specifics of the benchmark it might however be difficult to provide evidence for a deliberately inaccurate submission. 15. Not applicable. Seite 4 | 8 16. Panels should be chosen in order that the resulting benchmark adequately represents the market. However, there should be conditions for the panel contributors. E.g., they should have proper organisational mechanisms in place. They need to have adequate processes for identifying, avoiding and, if this is not possible, managing conflict of interest. They should have processes for producing and documenting their contributions in a clear and transparent way. 17. To ensure the representativeness and integrity of the data, survey data should be: • verified by the benchmark sponsor, e.g. by verifying documentation and cross-checking • published in order to enhance transparency • scrutinized intensively by the benchmark sponsor (e.g. checking for unusual changes in submissions) • adjusted by calculating benchmarks as adjusted averages (elimination of outliers) to reduce the vulnerability for manipulation • deducted by contributors in accordance to clear guidelines 18. Large panels will reduce the risk of manipulation and misconduct. It would also improve the economic quality of the benchmark since it would better represent market activities. A greater geographical dispersion of the participants would also support the goal of having a representative and economically meaningful benchmark. 19. See replies to questions 28 and 29. 20. Potential litigation risks that may arise from a firms participation and increased regulatory burdens could potentially result in contributors exiting the benchmark setting process. Benchmarks themselves share some of the characteristics of a public good, meaning that their benefits are not exclusive to the submitters. 21. Mandatory reporting requirements could prove useful, as they increase the share of the market that is represented by the benchmark. However, a threshold (e.g. market share) should be considered to avoid excessive burdens on minor submitters who do not significantly contribute to the representativeness of the benchmark. 22. Allowing the regulator to exercise control and oversight over individuals as well as firms, will significantly increase the ability of authorities to oversee benchmarks effectively and take action in relation to any misconduct. The existence of sanctions will provide a powerful incentive on firms to ensure they act properly Seite 5 | 8 and in compliance with the relevant regulatory requirements. Disadvantages would be increased compliance costs for firms and an increased supervisory burden on the regulator. 23. It is advisable to have the responsibility for adjustments of inadequate data – if any – rest with the index provider. Currently, grounds for supervisory measures with regards to the index provider are being developed and shall include adequate elements of governance, transparency and non-discriminatory access to the relevant index information. 24. Currently, there is no formal auditing process with regards to the index provider. 25. Not applicable. 26. The internal audit controls of data contributors are being evaluated; so far, audit controls appear to have been insufficient. More severe control mechanisms are likely to be necessary and will eventually be based upon the final outcome of the ongoing evaluation. However, under current legislation, audit control measures and validation procedures can only effect contributors as index providers and publishers are outside the scope of regulation. 27. With regards to the index provider, a formalized validation procedure would allow for a general plausibility control; with regards to the contributors of relevant data, integrity is likely to increase significantly. Generally, advantages are an increase of integrity and reliability while on the other hand formal procuders will increase the costs of index provision and possibly supervision and may make market proximity hard to achieve. 28. As opposed to the process of validation, responsibility for a final audit should not rest with the index provider. Instead, the responsibility depends on the nature, depth and frequency of the audit required de lege ferenda and should be conducted either by the supervisory authority or an independent auditor in accordance therewith. 29. Generally, any governmental regulation of benchmark activity should be installed with caution and should concentrate on those rates that are frequently used by the markets and are (due to their nature) open for manipulation. While regulation would presumably increase the participants‘ integrity and awareness, it may on the other hand in some areas create an inadequate Seite 6 | 8 demand of effort and thereby make the use of benchmarks generally less feasible. Chapter 3: The Purpose and Use of Benchmarks 30. Generally, the use of benchmarks may be restricted. For investment funds, as an example, the use of benchmarks is already restricted. Provisions for the use of indices (either with regard to index-tracking or the use of derivatives which refer to indices) apply in Europe to all UCITS. Please refer to the answer to question 6. 31. Such strict allocation of specific benchmarks is considered problematic for the respective activities and terms of use would have to be determined beforehand. Obviously, this may only be feasible e.g. with large standardized contracts. Currently, BaFin sees no grounds for intervention or regulation. 32. Generally, there are no objections against the use of „wholesale“ benchmarks in retail contracts. A level playing field should be aimed at with respect to the control of non-financial benchmarks in relation to the terms to be established in the financial sector. Wherever there are nonfinancial regulatory (public) institutions involved, a reasonable level of cooperation should be established and/or upheld. 33. The allocation of responsibility depends on the regulatory measures taken, for responsibility itself may otherwise not be enforced. With regard to regulated entities, some degree of responsibility may always be assumed for reputational reasons, regardless of the actual regulation. Chapter 4: Provision of Benchmarks by Private or Public Bodies 34. The qualification as a public good has to be determined individually, whereby aspects such as non-rivalry and nonexcludability have to be taken into account. Currently, none of the known indices are considered a public good. 35. It may be appropriate to distingiush between benchmarks provided by public or private institutions: While benchmarks provided by a public body are already subject to regulation on another (i.e. institutional) level and therefore do not need any further governance by (e.g.) financial regulators, private Seite 7 | 8 benchmark providers should be governed along the terms established above (see answer to question 12). 36. Advantages: • less potential conflicts of interest in the collection of data (given no governmental issues are concerned) • public influence in the compilation process may be possible Disadvantages: • potential conflicts of interest whenever other governmental goals may be concerned (e.g. potentially low inflation rates in times of economic crisis) • possibly less flexibility and speed in development or adopting to new circumstances • possibly less variety because of the limited number of potential index providers and lack of competition 37. There is no obvious reason for a general provision of benchmarks by public bodies. However, in the event of market failure (e.g. public good) a public body may adopt the role oft he provider. Chapter 5: Impact of Potential Regulation: Transition, Continuity and International Issues. 38. The public index provider’s neutrality may be endangered whenever other governmental issues are concerned. Hence, the less dependent a public provider is on the government, the less conflicts of interest may arise (e.g. public foundation vs. administrative body). 39. One of the challenges is whether there is an appropriate and eligible alternative to an existing index or benchmark or not. Contract parties chose an existing benchmark or index for some specific reasons and the question is whether or not the alternative benchmark can cope with these requirements. Another crucial factor with respect to liquidity issues is the acceptance of the alternative benchmark. Market-led transitions from one benchmark to another, e.g. from FIBOR to LIBOR, took place as a result of surrounding circumstances and changes. We are not aware that impact assessments were conducted. With regard to an estimate of future costs experiences from better regulation-efforts. i.e. other impact assessments, suggest that the costs will not fall below an amount of EUR 50,00 per transition per object. Seite 8 | 8 40. While a mandatory use of benchmarks is generally seen as problematic (see answer to question 31), in cases of a transition from one benchmark to another regulatory measures may be considered. 41. Coordinated action by all relevant financial market places is of the essence in order to avoid regulatory arbitrage. Within the European Union, respective legal measures should be taken. 42. + 43. Any change in the way a benchmark is calculated has a potential impact on the value of this benchmark and its future development. Such an effect would likely be brought about by the introduction of new regulation as well as by the better enforcement of existing regulation with regard to the calculation of a benchmark or index. However, it is not the task of financial regulation and supervision to consider the commercial interests of small and medium-sized enterprises or of other private or legal persons which have been trading in financial instruments based on a certain benchmark or have taken out a loan with a variable interest rate. Instead regulation and supervision should only seek to ensure the integrity and stability of financial markets. 44. Not applicable (no direct us of benchmarks in the regulatory sector, see reply to question 1-3). 45. Not applicable (see reply to question 44). 46. Not applicable (see reply to question 44).