Esther Pasztory - California State University, Sacramento

advertisement

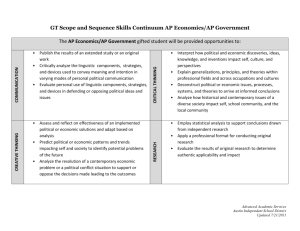

Paradigm Shifts in the Western View of Exotic Arts Esther Pasztory What exactly do we mean when we say "the West"? We generally refer to a geographic area the core of which is Europe and North America after the sixteenth century. Sometimes we add Australia and less frequently Latin America. (Latin America is seen to be some kind of a mixture of the West and the Nonwest.) Usually, we include the Classical Antiquity of Greece and Rome, but not the European Middle Ages, or ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. The epicenter of the "West" is actually even smaller, being limited to the civilization of western Europe and some of the U.S. Non-geographically, the "West" is also the concept of a scientific and technological culture that has come to colonize the "Nonwest"—politically, economically, militarily and ideologically—over the last four centuries. The West has had a dominating world discourse for so long because its scientific and technological approach revolutionized the relationship of humans to nature and to one another. This is what we call "modernity". The concept of modernity is confused in the West because aspects of industrial culture are indissolubly blended with western ideological values. Nonwesterners easily take apart what they see as a more or less neutral modernity (cars and cell phones) from western beliefs. To put it another way, modernity happened in the world in western clothes—it could have happened in another guise, perhaps East Asian, and that would have been another story. (1) Modernity sowed the seeds of globalization, and globalization has resulted in the emergence of the Nonwest away from the actual and ideological domination of the West. For example, today, China's relation to Africa is as, or more important than, it's relation to the West; and the world watches more Indian Bollywood films than American Hollywood ones. Nonwesterners are relating to each other without the mediation of the West. This essay is about some of the shifting western attitudes towards nonwestern arts and cultures especially in the last century. Until fairly recently, the West looked on the Nonwest as exotic—that is, as something not quite normal from its point of view, alternating between admiration for or denigration of it. Despite the patronizing tone of much western commentary, the West appears to have needed its idea of the Nonwest in order to define its own identity as always in opposition to it. As a result of this, westerners have not wanted to obliterate nonwestern culture; on the contrary, many idealistic westerners have tried to encourage native arts and cultures to remain native (i.e. exotic), while simultaneously modernizing them to fit into the present world. They saw nonwesterners as potentially split between "authentic" native and modern aspects, which is ironic because they have been unable to see themselves as split between their modernity and westernness. I will discuss this western process of "nativization" in the second half of this essay. Modernization has progressed so far in the arts that many of the works of nonwesterners are indistinguishable from the works of western artists, thus wiping out the difference between west and Nonwest entirely in this realm. The West/ Nonwest dichotomy is, therefore, in the process of ceasing to exist in the twenty-first century. Yet the story of the paradigm shifts of how this came about is worth telling. Exoticism has been a part of the West at least since Herodotus' Histories in which, to the Greeks, the Egyptians were a mysterious, ancient civilization who did everything in reverse, the Scythians bloody barbarians, the Persians contemporary powers to emulate and beware of, and the Chinese perhaps only an indirect myth. (2) The West, in the form of Classical Antiquity, was then at the very edge of a great world Oriental system and its reaction to others was both to criticize and to admire. To them, the Orient was the equivalent of the Nonwest. The word "Orientalism," as Said and others use it, is a western denigrating attitude towards the Orient as a place of tyranny, irrationality, laziness, effeminacy and unchanging-ness. (3) Paradoxically these negative traits can also be seen as positive in reaction to the West's own sense of its mechanical rationality, lack of spirituality, creativity and a human dimension. Both types of Orientalism were current in ancient Greece. Primitivism, a denigrating and/or admiring attitude to less developed small-scale societies, was particularly evident in ancient Rome whose military was conquering "barbarian" tribes throughout Europe and the Near East. Tacitus in particular praised the barbarian Germans for their bravery, loyalty, and honesty despite the poverty of their culture and in contrast to the soft and corrupt Romans. (4) These ambivalent attitudes to foreign and exotic peoples from Classical Antiquity were passed on in later European culture with the admiration of these texts, especially from the Renaissance of Early Modern times to the present. It is not my aim to recite the long history of exoticism in the West, but merely to point out its existence prior to the eighteenth century when modern attitudes emerged. Generally, the earlier centuries up to the sixteenth and seventeenth saw other peoples through the lens of religion, dividing the world into Christians and heathens. There was little interest in the heathens' art in as much as the concept of "art" had not even been formulated in the West. Strange objects had curiosity value and along with fossils, bones and shells they found their way into curiosity cabinets as individual oddities. The gods of other peoples were represented in engravings as Christian devils. In some seventeenth century prints of the Aztec patron god Huitzilopochtli, the image resembles neither Aztec gods nor Aztec style but the devil. (5) In the religious view of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, all nonwestern images were evil heathen idols and devils. A major paradigm shift occurred in the eighteenth century that can be described as "schizophrenic": the simultaneous view that nonwesterners were both greater than and lesser than westerners, i.e., "noble savages." This was the result of the de-emphasis of religion, in particular Christianity, in philosophy and scientific thought, and (one might say) the concurrent mystification and deification of art as a universal phenomenon. The word "aesthetics" was coined by Baumgarten in 1750 to describe this newly conceptualized realm of human activity. (6) Creativity in the arts had become the mysterious work of "geniuses," and the modern concept of art, as something material but transcendental, was born. Most cultures do not have a word for this western concept of "art" and often someone from our culture invented one for others. For example, the Chinese and Japanese words for art were created by the American Ernest Fenollosa, who admired everything Oriental in the 1870's in Japan. (7) Along with other eighteenth century views of human activities, the arts and aesthetics were seen as universal. The devilish idols of the past century had become the works of art and a steady stream of travelers went East and West to search them out to illustrate and publicize in books. New explorations were undertaken in the eighteenth century. However, this time the paradigm was not the bloody conquest of Mexico and Peru, as it had been in the sixteenth century, but the sexual welcome of South Sea Island women. The newly found natives were friendly, and these explorations raised questions about the nature of man in the state of nature, that is, in contrast to the prohibitions and inhibitions characteristic of civilized western life. As early as the sixteenth century Montaigne audaciously presented the New World cannibal as superior to the Frenchman— following, of course, the time honored device of Tacitus. (8) Primitivism and Orientalism began full force in the eighteenth century. Nonwesterners were still considered to be bloody, lazy and promiscuous, but these qualities were excused and admired on the grounds of greater naturalness and honesty in their life than in life in the West. The eighteenth century was the time of the Marquis de Sade, whose violence was accepted as a part of human nature. (9) Overall, the eighteenth century was positive towards others while the nineteenth was somewhat more negative. The twentieth has been remarkably positive. The history of Primitivism and Orientalism is one of ambivalence over or undervaluation, depending on what the West looks for as a corrective in itself. Only rarely, if ever, is the nonwestern other seen for what it is. The center of both Primitivism and Orientalism was and is Paris. It is here that Bougainville brought the news of the friendly Tahitian women (10); that Montesqieu wrote the Lettres Persanes (11); that Picasso discovered African art; and the first exhibit of nonwestern contemporary art, Les Magiciens de la Terre, was held in 1989. (12) A secondary center is London, with the exoticism of Captain Cook (13) and Sir Richard Burton (14); the influential art of Henry Moore; and Third Text, the journal of contemporary nonwestern art established in 1987. (15) Much of the rest of Europe followed these developments with some time lags. The effect of these primitivist tendencies on the arts of the West was very pronounced. We generally consider neoclassical art as cloyingly western, but around 1800 those simple, imaginary Greek forms had the power of the primitive. Like Picasso's African masks, the directness of Classic art annihilated the baroque and rococo styles of the previous century. The starkness of David's Oath of the Horatii (1784) was a revolution in its time. By 1900, the Neoclassic lost its force to shock and destroy and stronger measures were needed to reveal the primitive inside the civilized western soul. The creation of Modern art with the inspiration of primitive art was a complex process that abandoned the western tradition of mimetic art for a new conceptualism. This shift was clever and necessary in that, by 1900, mimetic representation was taken over by photography and film media. The conceptual language of Modern art came closer to the rest of the world whose art had always been less mimetic. Modernism was thus potentially global from its inception. Fig. 1: Indian woman with Franz Boas and George Hunt holding up a blanket The overvaluation of the nonwestern in modernism helped to maintain the necessary fiction that these cultures have continued to exist in more-or-less unchanged form from their primitive Edens to the present time. Gauguin's glorious painted Tahiti (c.1890 to 1900) was a far cry from the real poor and decrepit Tahiti that he actually visited, being that it was neither fully native any more nor quite western. People in the West wanted to know how the natives had lived and not how they live today. Anthropologists like Franz Boas used blankets to cut out all signs of modern life in their nostalgic ethnographic photos. (Fig.1) (16) Modernization came to different parts of the world at different times and in different ways, but the consistent aim of many westerners was to prolong the traditional as long as possible and to record it in its last gasp. (So long, of course, as headhunting and human sacrifice were given up.) The western search was for a pure and uncontaminated exotic culture—uncontaminated by us—that could be voyeuristically experienced. It is what the Native American artist Jimmie Durham calls the search for "virginity." (17) The art collected, exhibited, and studied by us had to be similarly authentically traditional. During much of the twentieth century, many westerners, often art teachers, sought to revive the declining native arts in commercial workshops. While ostensibly for the benefit of the natives, this obsession with maintaining their authenticity was a desire on the part of westerners to maintain an "other" outside of themselves. Psychologically it can be said that this was to justify the existence of a hidden nonwestern "id" in rebellion against a western "ego", a split within the western self. Originally primarily an attitude of the elite intelligentsia, these ideas have filtered down via Hollywood films to a larger public. Nevertheless, modernist art (along with its primitivism) remained an elite taste in the West, and actual nonwestern art had an even smaller audience. This agenda came to its florescence in the theoretical attitude of what is now called Poststructuralism. In their most influential work, Anti-Oedipus (1972), Deleuze and Guattari idealized a new humanity that would live in a semi-schizophrenic mental state not governed by a (western, oedipal) ego but instead consisting of equal yet partial psychic elements supposedly characteristic of the non-rational world view of nonwestern peoples. (18) They compared the hierarchic structure of the ego psychology of western culture to fascism, and they imagined that the nonwesterner lived a more open and complete psychological life. Roland Barthes idealized the traditional Japanese ethos and aesthetic in the nineteen sixties in similarly glowing terms as if it still existed unsullied in his time, despite the thousands of Japanese cars rolling out of modern factories. (19) He admired the Japanese for being non-mimetic in their representations and for revealing the artifice behind representation in such cases as bunraku puppetry (1970). This Poststructuralist primitivism came out of Paris, the deep wellspring of exoticism in Europe. Its immediate antecedent was structuralism, associated with Claude LévyStrauss and derived from his 1940s trip to the Amazon and the encounter with threatened, vanishing cultures. The original French title of this account, Tristes Tropiques (1955)—translated as A World on the Wane (1961) in the first English edition—expresses all this guilt and nostalgia towards the nonwestern other. (20) Such a Primitivism was a part of the cultural revolutions of 1968 both in the US and Europe. The various interlinked utopian issues of free sex, "back to the land," and altered states of consciousness were all revolts against capitalist western cultures. Much Poststructuralist thinking, such as Deleuze and Guattari, were inspired by the events of '68. How did this Orientalism-Primitivism come to another shift ? It was not by the West and least of all by the U.S. It was demolished brick by brick by nonwesterners. While the West was imagining and emulating nonwesterners, they were critically evaluating the West and adapting facets of that life that they found useful. A wonderful 1945 painting by Omar Onsi from Lebanon shows a clutch of black-clad Lebanese women staring at a western painting of female nudes in an exhibition. (21) All this time the West has been watched and continues to be watched as eagerly as the West once examined others. This process is of course as old as contact. The Plains Indians adapted the horse and weapons of the white man in the eighteenth century. The anthropologist Giancarlo Scoditti told me sadly that the Kitawa Islanders where he did his fieldwork gave up their pottery for plastic containers. When he remonstrated with them in the name of beauty and tradition to keep the pottery going, they argued that plastic is more durable, unbreakable and in all ways superior to their pottery. Was he trying to keep a superior material away from them? It is we who live in a world of myth while nonwesterners are often remarkably pragmatic. Fig. 2: Untitled [Man Leaning on Radio], Seydou Keita These "primitives" didn't just adapt the horse and plastic, they also adapted the camera for their own purposes as a superior way to make images. The best known native photographer is Seydou Keita of Mali, who got a camera as a gift in 1935 and used it for snapshots while he made a living as a carpenter (Fig. 2). (22) He became a professional photographer in 1964, at about the time when, he said, his people began to lose their ancestral culture. By that he meant that people began to wear western clothes and wanted to look as modern as the figures in western magazines. He had props like bicycles and radios in his studio as well as costumes and accessories his clients could choose for their photos. Bamako inhabitants were photographed by him with sewing machines, radios or sometimes simple details like gloves or handkerchiefs. Of no interest to the West at the time, Seydou Keita's photographs were suddenly appreciated in the 1980s in Paris, and in 1991, he had a major exhibition. So much acculturation would have been considered a sign of inauthenticity in the past and seen as a regrettable development. But between 1950 and 1980, the "authentic" nonwestern native disappeared all over the world. Even the most remote Amazon villagers had access to camcorders and made applications to fund their own survival from granting agencies. (23) With such an inyour-face change, western taste starting in Paris and London made a major turn-around and began accepting these arts and peoples as the new "noble savages". The Metropolitan Museum now has nearly half a dozen Seydou Keita photos in its collection. This acceptance was neither immediate nor simple. The major question was how to classify these images—were they modern or native? An instance of this dilemma concerned the large Australian aborigine canvases that look like modern abstractions and would look at home in The Museum of Modern Art but when offered to museums by donors the museums did not know where to put them they seemed to be "contemporary art" but those curators did not want them. The curators of native art did not want them either because they were not traditional. These objects were in a classificatory limbo for a decade or more and their fate was uncertain. It was a fascinating cultural question as to which side the decision would fall. There was no one centralized decision—each institution made its own. The returns are now in: These are considered to be regional ethnic arts, not works of mainstream modern art. The aboriginal acrylics go with the bullroarer and the didjeridoo, not Picasso and Pollock. This protects western modernism as unique and it places the nonwestern squarely back in Orientalist and Primitivist territory. Contemporary artists of ethnic origin complain in vain. Here is Rashid Araeen, a Pakistani artist living in London and one of the founders of the journal Third Text: "Somehow I began to feel that the context or history of modernism was not available to me, as I was often reminded by other people of the relationship of my work to my own Islamic tradition...Now I am being told both by the right and the left, that I belong to the "Ethnic Minority" community and that my artistic responsibility lies within this categorization...you can no longer define...classify or categorize me. I am no longer your bloody objects in the British Museum. I am here right in front of you in the flesh and blood of a modern artist. If you want to talk, let us talk. BUT NO MORE OF YOUR PRIMITIVIST RUBBISH." (24) Or, one could listen to the sarcasm of the Native American conceptual artist Jimmie Durham. "Virginity and primitivity are the same value to you guys...So you have a neverending search for true virgin territory..."Untouched Wilderness"...[and] "Breaking New Ground." (25) Sorry, folks, the decision is, you are ethnic. This decision allows the westerner to have an alien other and not to have to live in a relatively homogeneous world in which all difference has been eradicated. In this contemporary nonwestern art, there is one great plus to the westerner—one does not have to feel guilty. It was always assumed that western influence would result in cultureless prostitutes and alcoholics out of the noble savage because, in fact, it often did. But looking at Seydou Keita photos, the westerner is exonerated: there are these healthy, beautifully dressed and intelligent people who are actually enjoying western culture while they likewise seem to take pride in their native roots. Those women in the patterned garments seem to express an African aesthetic in modern form. How exciting. Contemporary art outside the West was first accepted in Europe, particularly Paris, in the form of major exhibitions in the 1980s. This was also the time when Third Text (1987), a journal devoted to contemporary Third World art, was founded by the Pakistani Rashid Araeen and the Nigerian Olu Oguibe, both living in London. One obvious reason for this was that these were the locations where members of the former colonies gravitated and where postcolonial theory became important. One could say that Paris was the visual center while London was the intellectual locus of this trend. The appreciation of contemporary nonwestern art was important in that it reformulated the romantic loss notion of the Nonwest into a romantic gain. Plus ça change... The U.S. has been slow to take up contemporary nonwestern art as a positive development. For example, in the early 1990s there was a major African art exhibit in London that consisted of a traditional, "classical" part and a contemporary part. The "classical" part came to the Guggenheim Museum, the contemporary did not come at all. Various people close to the exhibit said that it wasn't of "high enough quality." The fact remains that except for unusual circumstances, such as Susan Vogel's Africa Exploresexhibit of 1988 (26) or the Australian aboriginal acrylics at Asia House the same year (27), the U.S. public has had little exposure to contemporary nonwestern art. The U.S. has resisted the nonwestern contemporary in the museum and academy because it destroys the illusion that pristine cultures unaffected by globalization still exist. We need to visit another culture to rest from ours, and these contemporary artists are in effect saying that there is no such place. In so far as globalization has been accepted as a good or at least inevitable process, nonwestern contemporary art has also been accepted as proof of the resilience and creativity of the nonwestern world. The new ethos is that we all now inhabit the same world. The West's ambivalent relationship to the Nonwest is especially evident in the area of "art." As mentioned earlier, most cultures, including the ancient Greeks, have not had a word for art and aesthetics, which are concepts from eighteenth-century European philosophy. In most areas this is being rectified by westerners. The concept of art is as much an aspect of globalization as fast food franchises and it began quite some time ago. At the end of the nineteenth century, Ernest Fenollosa invented terms for art in both Chinese and Japanese that have now become standard usage. Fenollosa went to Japan after the Meiji restoration, at which time everything western was taught in the schools of art as something modern. He advocated a return to tradition and was made curator of the Imperial Museum. (28) Despite his love of the traditional, he urged that modern traditional art (an oxymoron) should also simultaneously satisfy contemporary taste. Fenollosa is the prototype of the westerner who determines what is "art" in a nonwestern context, who is nostalgically promoting tradition while also promoting western taste. Fenollosa was not unique. It was my privilege to meet James Houston, the Canadian artist working in the 1960s who created a contemporary art movement among the Eskimo, now called Inuit. (29) This movement and many others like it were done in compensation of the destruction of the natives' economy as an alternative way of making a living. These new art traditions became so integral to society that they came to substitute old activities such as hunting. Inuit men competed in carving soapstone figures as they had once competed in hunting seals. The city-dwelling westerners who bought their carvings wanted traditional themes such as polar bears and seals. The Inuit were therefore representing in art a life they were no longer living. James Houston and other idealist/commercial advisers determined the style of the works. In 1948/49 he made drawings for the Inuit as models for the sculptures. He exhibited the sculptures in Montreal, creating an audience and market. Some years later he introduced printmaking. The Inuit had made nothing like them traditionally. Although there were small ivory figures, the soapstone carvings were entirely new. Houston went on developing the style by selecting what he liked, which was a combination of childlike awkwardness with a stylization reminiscent of Henry Moore. This is one of the places where the primitive inspiration of Modern Art and the spread of modernist aesthetics into primitive art came full circle. Henry Moore is not mentioned accidentally—he defined Houston's Inuit aesthetics. Fig. 3: The Enchanted Owl, Kenojuak Among the Inuit, printmaking became the province of women, a gender division presumably appropriate to the primitive. The successfully selected works were religious or quasi mythological, as can be seen on theEnchanted Owl and Perils of the Sea Travelers in Houston's 1960 publication titled Eskimo Prints. (Fig. 3) (The owl was a bestseller and I remember seeing it in many New York homes.) The Inuit carvers and printmakers were professionally playing up a naivete in the name of tradition. As Janet Berlo's article indicates, many artists were not satisfied with these parameters and made images of modern life unlikely to sell then. (30) In the 1980s Inuit artists made fun of the sculptural tradition by making nontraditional subjects such as stone airplanes and mobiles with antler and whalebone details that refer to the modern world and its arts. One would not think that traditional Australian aborigine figuration and ornamentation would lend itself to contemporary art, but it has—at least twice. In the 1930s the anthropologist Donald Thompson suggested transferring rock and bark paintings to larger bark panels for commercial sale (1935–37). Kangaroos and fishermen were some of the popular subjects, with the nice naïve/sophisticated detail of showing the internal organs. (31) All this is similar to the Inuit situation and was sold to museums, universities and collectors as aborigine art; as a result, aborigine "pride" took off in the 1950s and '60s. Fig. 4: Australian Aboriginal Painting But the really interesting development took place in the 1960s with the work of the artist Geoff Bardon, who saw the possibility of aborigine art writ large in modern-looking acrylic canvases. (Fig. 4) "He provided the initial motivation, procured and organized the materials and assisted in promoting the artists and the sale of their works. To the aborigines Bardon was the 'painting man' and they now refer to his days at Papuynia s 'Bardon-time'. (32) Bardon was a Sydney art student who went to teach children in Papuynia in 1971. Between 1971 and 1972, six hundred and twenty paintings were created under his tutelage. There have been many other art "advisers" since. Bardon's idea was that the form, abstract looking paintings in acrylics, was new—but the content was old. The enthusiastic literature, such as the Dreamings catalogue of the Asia House exhibition of 1988, emphasizes the "nativeness" of the images evident in the titles and descriptions. For example there isSugarleaf Dreaming at Ngarlu (1986): mythical women dance and collect sugarleaf; there are two actual births and they gather yamirlingi (well, it's an exotic word, whatever it is.) It looks like a very nice abstraction. Some paintings are meant to be geographic or climate maps. Possum Spirit Dreaming, one of the largest paintings at 213 x 701 cm, combines geography and story. Usually these are too complicated and shorthand to make much sense to the westerner, to say nothing of the fact that according to the authors not everything is divulged to outsiders. However, the western owner of such a painting feels that he or she has a bit of authentic and native art, as it looks like a great modern abstraction above the couch—the best of both worlds. Jackson Pollock comes to mind looking at these convoluted dot paintings, although instead of the free-wheeling drips the dots are precisely and calculatingly placed. (It's okay for western art to be messy; nonwestern art has to be neat.) In her book Contemporary African Art (1999), Sidney Kasfir has a whole chapter on what she calls "Patrons and Mediators." (33) The most successful and colorful of "art mediators" in Africa, according to her, was McEwen of Rhodesia in the 1960s, who created a school of stone sculpture where actually none had been before. An intellectual interested in Focillon and Jung, he taught the artists to explain their works in terms of their own individuality and the collective unconscious of their Shona ethnic group. Descriptive realism and 'academic' style were forbidden and a Henry Moorish modernism was expected. In 1969, forty six sculptures exhibited at MOMA were billed as "New African Art from the Central African Workshop School." Despite such attempts to control form and content, individual native artists emerged outside the workshop and eventually art making became decentralized. Although I met James Houston in the 1960s I paid no attention to his chosen contemporary Inuit collection or to what he said about it. I was primarily interested in "authentic," archaeological and traditional art, and the problem of native contemporary art only found me by accident in 1976. I was exploring the abandoned ruins of the American Southwest and looking for a research topic. Spending a few days in Santa Fe, I wandered into the Institute of American Indian Arts Museum and, before I could respond to the works, I was buttonholed by a staff member who said quite aggressively that I was not to expect any cute pictures of Indians performing quaint ceremonies because Indian artists were now a part of the mainstream of modern art doing abstractions. "But you whites won't buy the abstractions, you just want the oldfashioned ritual scenes which we won't do any more." The person was angry and I escaped as soon as I could. I never did a project on the ruins but the dilemma of the contemporary native artist stayed with me to the present. I eventually taught seminars on the subject titled "Modern Art Outside the West" starting in 1995, which was the prototype for "Multiple Modernities." (34) I have no idea what art works I saw in Santa Fe in 1976, but American Indian Arts Magazine illustrated the sort of work I might have seen. According to the illustrations in the magazine, in the mid-1970s artists worked in a contemporary style with some native elements but without descriptive realism: such as David Paladin's Pueblo Kiva (1976) with a mask and multiple faces, and his Birth of the Sun, with its geometrically stylized figures; or Helen Hardin's Recurrence of Spiritual Elements (1973) and Prayers of a Harmonious Chorus (1976), with their interpenetrating features blurring reality. I knew nothing about the much maligned paintings of "ritual scenes" but it was not difficult to find out that they had been encouraged by a "mediator", Dorothy Dunn in the 1930s. (35) Dorothy Dunn had a degree from the University of Chicago and founded and ran a Studio in Santa Fe for Indians between 1932 and 1937, though as an institution it lasted far longer and was very influential. Every Indian artist born between 1915 and 1940 was trained there or by its alumni. The mission of the school was to create art that was as good as traditional art and also maintained the "Indian" characteristics of clear outlines and flat colors. Backgrounds were to be flat for a "primitive" look which also made them "modernist" to some extent. The artists were told that they needed little training because their style was already in their "unconscious". Pena's Gourd Dance (1939) and Tsihnahijinnie's Navahho N'Da (1938) are perfect examples of this elegant, timeless style. There were regional variants of styles, such as the more dynamic Kiowa styles of Oscar Howe's Dakota Duck Hunt (1947) and Buffalo Hunter (1938). Note that all these subjects were native. And if Oscar Howe's Umine Woman Dancer (1939) and Harrison Begay's Navaho Feather Dance (1942) remind one of Oriental art—such as Chinese painting or Persian miniatures—that is not accidental. American Indian art was promoted as a high art like traditional Asian art, but modern western art was to be alien to it. Fig. 5: Luiseño, Fritz Scholder The reaction against this western idea of "Indianness" is something I encountered on my visit in 1976, although by then it was not new. One of the leading figures of the reaction was Fritz Scholder, an artist who taught at the Institute from 1964–69 and who influenced many younger artists. (36) His view of Indian identity is cosmopolitan and ironic. In one series of lithographs, atypical Indians are posed with Paris landmarks such as the Eiffel tower (1976). Having come across these in American Indian Arts Magazine, I felt that they expressed the idea that the Indian had left the reservation behind, only people didn't know it. Later, Fritz Scholder told me that this series was based on turn-of-the-century photos of Indians in Paris that he had come across. (37) Indian identity remained his subject, as in the multiple Indian faces that include cigar store Indians in one painting, or the head of an Indian with a feather bonnet as the sign of a shopping mall called Pueblo Bonito Plaza. The real Indian is not wearing a feather bonnet any more: he stands in front of French wallpaper (1976); in sunglasses and ascot, he could be anyone. Ironically, this last is entitled Luiseño, the tribal group Scholder belonged to—although he was only one-quarter Luiseño, thus raising the question of who is biologically and or culturally "Indian" in any case. (Fig. 5) One could say that Fritz Scholder was a sort of Seydou Keita with an attitude. Fritz Scholder didn't just paint Indians, he was interested in many other subjects. Nevertheless, his reputation was made as an "Indian painter," and the art world was not interested in his non-Indian work. Like Rashid Araeen, he was unable to transcend the ethnic designation of his art to be considered simply as a modern artist. In every case discussed so far, the aim of the western "mediators" was to maintain native art and identity in the face of westernization, opposing or softening colonial political and economic forces. In a number of cases traditional art was presented as more commercially viable because the westerner is positively interested in and looking for an exotic native quality in what in considered nonwestern art. Nevertheless, the westerner could not deal with native quality unless it was mediated through a cognate western form, which was the language of modernism. This lingua franca of the twentieth century was incredibly malleable because it had rejected academic verisimilitude in favor of abstraction and stylization. Narrative, figurative, and totally abstract images were possible simultaneously. The work of certain artists—Picasso, Henry Moore, Jackson Pollock, and certain historical periods such as Persian miniatures or Medieval European art—were mostly covertly presented as models. At the same time it was assumed that the native artist already had such approaches inside him; they just had to be nurtured. The mediator often "taught" by selecting what he liked and the associations he or she made in his or her mind. At the other end, the buyers did the same in interpreting and evaluating the art they saw. A more precise illustration of how this process of traditionalism and modernism interacted is illustrated in the work of Elena Izcue, a Peruvian textile artist who can be considered both a mediator and an artist in one person. (38) Izcue was interested in incorporating ancient Peruvian art in her own primarily textile designs and in teaching her Peruvian compatriots how to do it in an active life from the 1920s to the 1950s. In the 1920s, she was a part of the artistic circles in Paris and studied with Leger. In the 1930s, she also exhibited her textiles in New York. In 1941, she founded a School for Decorative Art in Lima and, in 1955, was one of the founders of the Contemporary Institute of Art in Lima. Elena Izcue and her contemporary critics and purchasers felt that Pre-Columbian Peruvian motifs should inspire modern Peruvian art. When she went to Paris, a collector friend, Rafael Larco Hoyle, sent with her an extraordinary Pre-Columbian Peruvian textile to be exhibited there. (That "Paracas" textile is now in the Brooklyn Museum.) Elena Izcue thus justified her own work in terms of the Paracas textile. In addition, while in Paris, she published a book in 1926 entitled "Peruvian Art in the Schools," which detailed the way in which ancient native art should be used by simplifying and stylizing native motifs even further then they already were from realistic depiction, thereby making them contemporary. Izcue's designs on silks illustrate this process of radical simplification. Her work and the Paracas textile were both a hit in New York in the 1930s. Her American friend and Peruvian specialist, G.H. Means, wrote a brief article about her in which he praised her approach and explained how traditional and contemporary were supposed to interact from the western point of view: "She has the ability to separate from a highly esoteric ancient model its aesthetic kernel, and further the ability to interpret the very essence of the design in modern and practical form...Her invariable good taste and her profound intelligence have permitted her to take as a guiding rule the principle that nothing is more impressive than simplicity...she strips from it [her native model] all those parts which the modern mind would find grotesque..." (39) Fig. 6: Ethnography, David Siqueiros Means could have been speaking for much of the attitude of the twentieth century, which wanted to receive a native message through a taste formed by modern art. While this brought exotics and exotic art into the western world, it also left them in a straightjacket in which there was little room to move. That such incorporation of the native into the western world by stripping down was artistically sterile was discovered sooner or later by all native artists and they moved against it. Some Inuit abandoned bears to make stone airplanes. Native Americans in particular commented on western and Indian ideas of "Indianness." Australian aborigines living in cities, away from their rural cousins under the influence of mediators, began to paint the horrendous experience of colonialism. Death in Custody (1987), by R.H. Campbell, represents the mistreatment of aborigines.Massacre (1992), by Harry Wedge, is a similarly violent subject but done in the dot painting style; it is an ironic comment on the nostalgic dot paintings. Who buys such paintings? Only a sophisticated collector aware of mainstream art could be interested. Who wants a photorealist Aboriginal painting like Road to Redfern (1988), by Lin Onus, or a stylized figure likeWoman, by Bancroft? (40) At this point all ethnic designations disappear and the work could be from anywhere in the world. Now, nonwestern artists are their own "mediators" and explore native and western identities in one way or another in their work. I will refer to two examples by way of conclusion. The first is from the first part of the twentieth century, David Siqueiros' Ethnography (1939), now at the Museum of Modern Art, which shows a Mexican peasant whose face is a Pre-Columbian mask (the wooden original is in the American Museum of Natural History). (Fig. 6) The man looks through those unseeing eyes out of a stylized face as if to say "the past still lives in me," i.e., you cannot destroy the traditional because it comes back like a ghost to haunt you. This is the insight of the first half of the twentieth century. Fig. 7: "Self portrait: but You Don't Look Indian...", Vivianne Gray The second image is a sculpture by the Native American artist Vivianne Gray, in whose figure an actual mirror forms the face. The caption says: "Self-Portrait: But You Don't Look Indian..." (Fig. 7) As it is obvious, we only see ourselves in the mirror. The truth of the recent past is that the more we look into alien and exotic arts the more we see ourselves: our arts, our theories, our misinterpretations, our fantasies. Nonwestern contemporary art is a new mirror which reflects whoever looks into it with whatever preconceptions and theories they have at the moment. There is no ancient substratum in it, only an eternal present. ENDNOTES 1. The difference between the cultural evolutionary stage termed "modernization" and the particular nature of a civilization termed "insistence" is a major topic of my book. Esther Pasztory, Thinking with Things: Toward a New Vision of Art (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005). 2. Herodotus, The Histories, trans. Aubrey de Selincort, (London: Penguin Books, 1972). 3. Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon, 1978). 4. Tacitus, The Agricola and the Germania (London: Penguin Books, 1970). 5. Elizabeth Hill Boone, Incarnations of the Aztec Supernatural: the Image of Huitzilopochtl in Mexico and Europe (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1989). 6. Alexander Baumgarten, Theoretische Ästhetik: die grundlegenden Abschnitte aus der "Aesthetica" (Hamburg: F. Meiner, 1983). 7. Ernest F. Henollosa, Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art, an outline of East Asiatic Design, (London: W. Heinemann, 1912). 8. Michel de Montaigne, The Complete Essays, trans. R.A. Screech, (London: Penguin Books, 1993). 9. Laurence L. Bongie, Sade: a Biographical Essay (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998). 10. Louis Antoine de Bougainville, Voyage autour du monde, trans. John Reinhold Forster (London: J. Nourse and T. Davies, 1772). 11. Charles Montesquieu, Persian Letters (1721), trans. J.C. Betts (London: Penguin Books, 1973). 12. Jean-Hubert Martin (coordinator), Magiciens de la terre (Paris: Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1989). 13. John Gascoigne, Captian Cook: Voyager between Worlds (New York: Hambledon Continuum, 2007). 14. Sir Richard Burton, The Arabian Nights (Garden Grove, CA: World Library Inc., 1991) 15. Third Text, journal published in London. Rasheed Araeen editor in chief. The first issue appeared in 1987. 16. James Clifford, Predicament of Culture (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988) 186. 17. Jimmy Durham, "The Search for Virginity", in The Myth of Primitivism, ed. Susan Hiller, (London: Routledge, 1991) 286–291. 18. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983). 19. Roland Barthes, Empires of Signs (New York: Hill and Wang, 1982). 20. Claude Lévi-Strauss, A World on the Wane, trans. John Russell, (New York: Criterion, 1961). 21. Omar Onsi, "Young women visiting an exhibition" (1945) in LIBAN: le regard des peintres, 200 ans de peinture libanaise (Paris: Institut du Monde Arabe, 1989) 133. 22. Andre Magnin, Seydou Keita (New York: Scalo, 1997). 23. James Clifford, Lecture on Contemporary Brazilian Indians (New York: Columbia University, 1998). 24. Rasheed Araeen, "From Primitivism to Ethnic Arts", in The Myth of Primitivism, ed. Susa Hiller, (London: Routledge, 1991) 172. 25. Durham 289. 26. Susan Vogel, Africa Explores (New York: Center for African Art, 1988) 27. Peter Sutton, Dreamings: the Art of Aboriginal Australia (New York: Asia House and George Braziller, 1988). 28. FENOLLOSA op. cit 29. James A. Houston, Canadian Eskimo Art (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1954) and James A. HoustonEskimo Prints (Barre, MA: Barre Publishing, 1967). 30. Janet Berlo, "Drawing (upon) the Past", in Unpacking Culture, ed. Ruth B. Phillips and Christopher B. Steiner, (Berkeley: University of California, 1999) 178–196. 31. Sutton 147. 32. Sutton 97. 33. Sidney Littlefield Kasfir, Contemporary African Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 1999). 34. The seminar "Modern Outside the West" was the reformulation of an earlier seminar I gave in the 70s and 80s entitled "Indigenous Artist-Western Collector." 35. J.J Brody, Indian Painters and White Patrons (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1971). 36. Lowry Stokes Sims ed., Fritz Scholder: Indian Non Indian (Munich and New York: Prestel, 2008). 37. Fritz Scholder, Personal Communication and Pasztory 95–96. 38. Natalie Majluf and Eduardo Wuffarden, Elene Izcue: el arte precolombino en la vida moderna (Lima: Museo de Arte de Lima, 1999). 39. Phillip Ainsworth Means, "Elena and Victoria Izcue and their Art", in the Panamerican Union, March 1936 p. 250 (bibliography 248–254). 40. These were among many images shown to me by the specialist in aboriginal art, Susan Zeller. FIGURES Fig. 1: Indian woman with Franz Boas and George Hunt holding up a blanket. American Museum of Natural History James, Clifford. Predicament of Culture, Harvard University Press, 1988 p.86. Fig. 2: Untitled [Man Leaning on Radio] Seydou Keita 1955, print 1997 Metropolitan Museum of Art Twentieth Century AAOA Photograph Study Collection 1997.363 Fig. 3: The Enchanted Owl Kenojuak, 1960, 24 x 26 Inuit (Eskimo) print Houston, James. Eskimo Prints, 1967, Barre, MA p. 34 Fig. 4: Australian Aboriginal Painting Fig. 5: Luiseño Fritz Scholder, 1975 Heard Museum aquatint, artist's proof, 11 x 15" Fig 6: Ethnography David Siqueiros, 1939 Museum of Modern Art Fig 7: "Self portrait: but You Don't Look Indian..." Vivianne Gray, 1989 Mixed Media 61 x 62 cm Ryan, Allan J. The Trickster Shift. BIBLIOGRAPHY Araeen, Rasheed. "From Primitivism to Ethnic Arts", in The Myth of Primitivism, ed. by Susa Hiller. London: Routledge, 1991. Barthes, Roland. Empires of Signs. New York: Hill and Wang, 1982. Baumgarten, Alexander. Theoretische Ästhetik : die grundlegenden Abschnitte aus der "Aesthetica". Hamburg: F. Meiner, 1983. Berlo, Janet. "Drawing (upon) the Past", in Unpacking Culture, ed. by Ruth B. Phillips and Christopher B. Steiner. Berkeley: University of California, 1999. Bongie, Laurence L. Sade: a Biographical Essay. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998. Boone, Elizabeth Hill. Incarnations of the Aztec Supernatural: the Image of Huitzilopochtli in Mexico and Europe. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1989. Bougainville, Louis Antoine de. Voyage autour du monde, translated by John Reinhold Forster. London: J. Nourse and T. Davies, 1772. Brody, J.J. Indian Painters and White Patrons. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1971. Burton, Sir Richard. The Arabian Nights. Garden Grove CA: World Library Inc., 1991. Clifford, James. Lecture on Contemporary Brazilian Indians. Columbia University, 1998. -----. Predicament of Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988. Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983. Durham, Jimmy, "The Search for Virginity", in The Myth of Primitivism, edited by Susan Hiller. London: Routledge, 1991. Gascoigne, John. Captian Cook: Voyager between Worlds. New York: Hambledon Continuum, 2007. Henollosa, Ernest F. Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art, an outline of East Asiatic Design. London: W. Heinemann, 1912. Herodotus, The Histories, translated by Aubrey de Selincort. London: Penguin Books, 1972. Houston, James A., Canadian Eskimo Art. Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1954. -----. Eskimo Prints. Barre, MA: Barre Publishing, 1967. Kasfir, Sidney Littlefield. Contemporary African Art. London:Thames and Hudson, 1999. Levi-Strauss, Claude. A World on the Wane,translated by John Russell. New York: Criterion 1961. Magnin, Andre. Seydou Keita. New York: Scalo, 1997. Majluf, Natalie and Eduardo Wuffarden. Elene Izcue: el arte precolombino en la vida Moderna. Lima: Museum Arte de Lima, 1999. Martin, Jean-Hubert (coordinator), Magiciens de la terre, Paris: Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1989. Means, Phillip Ainsworth. "Elena and Victoria Izcue and their Art", in the Panamerican Union. March 1936. Montaigne, Michel de. The Complete Essays, translated by R.A. Screech. London: Penguin Books, 1993. Pasztory, Esther. Thinking with Things: Toward a New Vision of Art. Austin: Texas University Press, 2005. Said, Edward W., Orientalism. New York: Pantheon, 1978. Stokes Sims, Lowry. Fritz Scholder: Indian Non Indian. Munich and New York: Prestel and the National Museum of the American Indian, 2008. Sutton, Peter. Dreamings: the Art of Aboriginal Australia. New York: Asia House and George Braziller, 1988. Tacitus. The Agricola and the Germania. London: Penguin Books, 1970. Vogel, Susan. Africa Explores. New York: Center for African Art, 1988.