Accounting-based covenants and credit market access

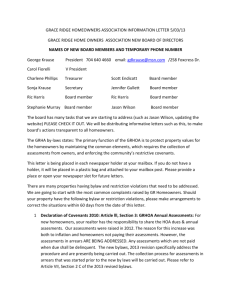

advertisement