Mark`s notes on terminology and references

advertisement

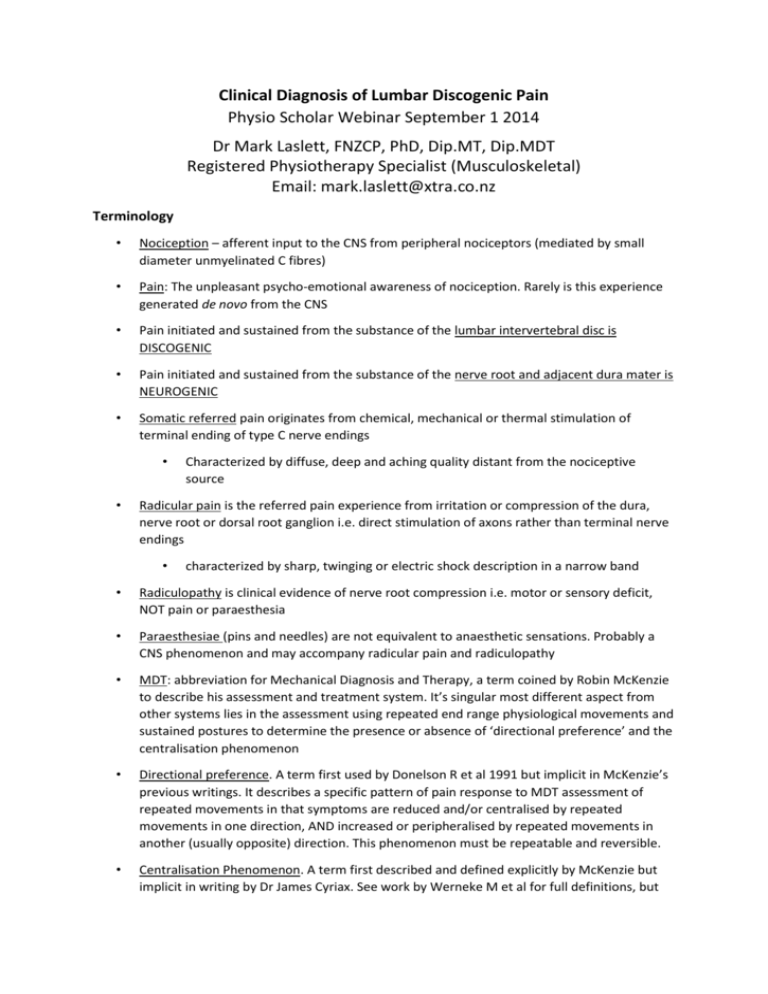

Clinical Diagnosis of Lumbar Discogenic Pain Physio Scholar Webinar September 1 2014 Dr Mark Laslett, FNZCP, PhD, Dip.MT, Dip.MDT Registered Physiotherapy Specialist (Musculoskeletal) Email: mark.laslett@xtra.co.nz Terminology • Nociception – afferent input to the CNS from peripheral nociceptors (mediated by small diameter unmyelinated C fibres) • Pain: The unpleasant psycho-emotional awareness of nociception. Rarely is this experience generated de novo from the CNS • Pain initiated and sustained from the substance of the lumbar intervertebral disc is DISCOGENIC • Pain initiated and sustained from the substance of the nerve root and adjacent dura mater is NEUROGENIC • Somatic referred pain originates from chemical, mechanical or thermal stimulation of terminal ending of type C nerve endings • • Characterized by diffuse, deep and aching quality distant from the nociceptive source Radicular pain is the referred pain experience from irritation or compression of the dura, nerve root or dorsal root ganglion i.e. direct stimulation of axons rather than terminal nerve endings • characterized by sharp, twinging or electric shock description in a narrow band • Radiculopathy is clinical evidence of nerve root compression i.e. motor or sensory deficit, NOT pain or paraesthesia • Paraesthesiae (pins and needles) are not equivalent to anaesthetic sensations. Probably a CNS phenomenon and may accompany radicular pain and radiculopathy • MDT: abbreviation for Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy, a term coined by Robin McKenzie to describe his assessment and treatment system. It’s singular most different aspect from other systems lies in the assessment using repeated end range physiological movements and sustained postures to determine the presence or absence of ‘directional preference’ and the centralisation phenomenon • Directional preference. A term first used by Donelson R et al 1991 but implicit in McKenzie’s previous writings. It describes a specific pattern of pain response to MDT assessment of repeated movements in that symptoms are reduced and/or centralised by repeated movements in one direction, AND increased or peripheralised by repeated movements in another (usually opposite) direction. This phenomenon must be repeatable and reversible. • Centralisation Phenomenon. A term first described and defined explicitly by McKenzie but implicit in writing by Dr James Cyriax. See work by Werneke M et al for full definitions, but the essence of the concept is that the patient reports a progressive retreat of referred pain towards the spinal midline over a short period of time (minutes to days), in response to repeated movements and posture instruction towards a specific direction. If the effect is maintained, prognosis is excellent. The phenomenon is highly specific to discogenic pain as revealed by provocation discography (Laslett M et al 2005) • Acute deformities. Lateral shift and acute lumbar scoliosis are synonymous and describe a lateral displacement of the trunk with respect to the pelvis. Thus a left lateral shift is a displacement of the trunk to the left of the pelvis. Acute lumbar kyphosis is a flattening or reversal of the normal lumbar lordosis. The lateral shift and kyphosis are commonly seen together. Acute fixed lordosis is a normal or accentuated lumbar lordosis than cannot be flattened or reversed by normal movement. These three acute deformities are quite distinct from the normal asymmetries commonly seen, and quite different from idiopathic scoliosis which are consequences of asymmetries of the vertebrae themselves. A more full explanation of the lateral shift and its management may be found in my paper13. The characteristic that most easily distinguishes these acute, acquired deformities that movements that an attempt to correct the deformity by a patient’s own movement or a movement imposed by the examiner, are obstructed and provoke the patient’s typical pain. An idiopathic deformity on the other hand is not painfully obstructed even though range of motion may be asymmetrical or limited from usual expectation. 1-12;14-19 References 1. Adams MA, Hutton WC. Gradual disc prolapse. Spine 1985;10:524-31. 2. Albert HB, Hauge E, Manniche C. Centralization in patients with sciatica: are pain responses to repeated movement and positioning associated with outcome or types of disc lesions? Eur.Spine J. 2011. 3. Albert HB, Kjaer P, Jensen TS et al. Modic changes, possible causes and relation to low back pain. Med.Hypotheses 2008;70:361-8. 4. Albert HB, Sorensen JS, Christensen BS et al. Antibiotic treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and vertebral bone edema (Modic type 1 changes): a double-blind randomized clinical controlled trial of efficacy. Eur Spine J 2013. 5. Alexander LA, Hancock E, Agouris I et al. The response of the nucleus pulposus of the lumbar intervertebral discs to functionally loaded positions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976.) 2007;32:1508-12. 6. Aprill C, Bogduk N. High-intensity zone: a diagnostic sign of painful disc on magnetic resonance imaging. Br.J.Radiol. 65(773), 361-369. 1992. 7. Crock HV. Internal disc disruption: A challenge to disc prolapse fifty years on. Presidential address:ISSLS. Spine 11(6), 650-653. 1986. 8. Donelson R, Grant W, Kamps C et al. Pain response to sagittal end range spinal motion: A multi-centered, prospective, randomized trial. Spine 16(Suppl), S206-S212. 1991. 9. Fagan A, Moore R, Vernon-Roberts B et al. ISSLS Prize Winner: The innervation of the intervertebral disc: a quantitative analysis. Spine 28(23), 2570-2576. 2003. 10. Fazey PJ, Takasaki H, Singer KP. Nucleus pulposus deformation in response to lumbar spine lateral flexion: an in vivo MRI investigation. Eur Spine J 2010;19:1115-20. 11. Hyodo H, Sato T, Sasaki H et al. Discogenic pain in acute nonspecific low-back pain. European Spine Journal 14(6), 573. 2005. 12. Kuslich SD, Ulstrom CL, Michael CJ. The tissue origin of low back pain and sciatica: a report of pain response to tissue stimulation during operations on the lumbar spine using local anesthesia. Orthop Clin.North Am. 1991;22:181-7. 13. Laslett M. Manual correction of an acute lumbar lateral shift: maintenence of correction and rehabilitation: A case report with video. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy 17(2), 78-85. 2009. 14. Laslett M, Aprill CN, McDonald B et al. Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests. Manual Therapy 10(3), 207-218. 2005. 15. Laslett M, McDonald B, Aprill CN et al. Clinical predictors of screening lumbar zygapophysial joint blocks: Development of clinical prediction rules. The Spine Journal 6(4), 370-379. 2006. 16. Laslett M, McDonald B, Tropp H et al. Agreement between diagnoses reached by clinical examination and available reference standards: a prospective study of 216 patients with lumbopelvic pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 6(1), 28. 2005. 17. Laslett M, Oberg B, Aprill CN et al. Centralization as a predictor of provocation discography results in chronic low back pain, and the influence of disability and distress on diagnostic power. The Spine Journal 5, 370-380. 2005. 18. Laslett M, Oberg B, Aprill CN et al. A study of clinical predictors of lumbar discogenic pain as determined by provocation discography. Eur Spine J 15(10), 1473-1484. 2006. 19. Laslett M, Young SB, Aprill CN et al. Diagnosing painful sacroiliac joints: a validity study of a McKenzie evaluation and sacroiliac joint provocation tests. Aust J Physiother 49, 89-97. 2003.