The Social History of `Early Modern` England, 1500

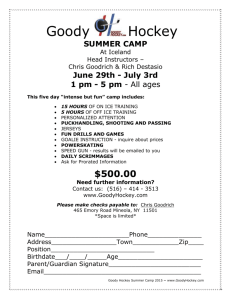

advertisement

The Social History of ‘Early Modern’ England, 1500-1700: An Introduction to the Historiography Professor STEVE HINDLE 1. The Historiographical Agenda: (or, ‘How and Why Did "Social History" Emerge?) a) The calling of the social historian: ‘understanding ourselves in time’ (Laslett 1965); cf. ‘structural amnesia’ (Goody & Watt 1968) b) what is ‘social history’?: a 4-phase evolution: i. Originated pre-war as ‘history with the politics left out’ (Trevelyan 1924). ii. Evolving into ‘residual history’ (Hobsbawm 1960): the study of those ‘hidden from history’ iii. Maturing as the junior-partner in the firm ‘Economic & Social History’ in the 1970s iv. Flowering as the ‘new social history’ in the 1980s: the history of society itself; 'societal history'?. The history of individual (and esp.) collective ‘experience’ (Thompson 1963); focus on ‘history from below’ (Thompson 1966). 2. Misguided Assumptions (or, ‘Did the Peasants Really Starve?: Laslett 1965) a) Demythologisation: Through rigorous analysis of archives (esp. parish registers), Laslett's famous question was, surprisingly, answered in the negative: the peasants might have gone hungry but famine was rare. Since c.1965 an avalanche of research has similarly overturned many assumptions: classic e.g. the history of the family (Wrigley & Schofield 1981; Wrightson 1998) i. young age at marriage?: in fact, very late: c.25yrs (male); 27yrs (female) ii. annual fertility?: in fact, very uncommon: ‘extended birth intervals’/'family limitation' iii. large/extended families?: in fact, overwhelmingly nuclear (average size 4.75) Similar surprises e.g. in the 'new social history' of kinship (very high levels of population turnover/kin dispersal: Cressy 1986); of religion (significant 'voluntary' commitment to the church: Duffy 1992). b) ‘interpretative polarisation’: still room for very significant debate over quantitative issues: e.g. nostalgia for the ‘World We Have Lost’ (Laslett 1965) vs. relief at escaping the ‘bad old days’ (Stone 1983) 3. The Ambiguities of ‘Early Modern’ Society (or ‘Were They Really Like Us?) a paradoxical society, partially familiar, partially alien (e.g. Ralph Josselin, vicar of Earl’s Colne, Essex: see Macfarlane 1976) a) patterns of change: in some respects, a society becoming more like our own over time? i. Population growth: from c.2.5m in 1520 to c.5.2m in 1650, esp. rapid in the 1570-80s (Wrigley & Schofield, 1981) ii. Price inflation: 6x increase in food prices c.1500-1600 (Outhwaite 1969) iii. Economic prosperity: spread in the ownership of consumer goods; increasingly elaborate 'material culture' (Weatherill 1988) iv. Immiseration: the emergence of the poor as a class (Slack 1988) v. Cultural change: esp. in the wake of the Reformation (NB the spread of literacy: Cressy 1980) b) Some important continuities i. A patriarchal society: all formal authority vested in men as husbands, fathers and rulers (Amussen 1988) ii. A hierarchical society: social & political order based on deference & obedience (Braddick & Walter 2001) iii. A rural society: 83% of population lived in the countryside even in 1700 (Clark & Slack 1972) a society at a crossroads: not easily characterised! 2 4. A Note on Sources & Methods (or, ‘How Do We Know?) a) application of traditional historical skills to novel sources: literature, diaries, letters, governmental records b) imaginative and conceptually sophisticated utilisation of unsuspected sources: parish registers, wills, probate material, archives of law courts and criminal justice c) BUT NB the evidential & interpretative vulnerability of some of this work. Key methods in social history: a) conceptualisation; + b) verification = c) credibility (Wrightson 1998) always remain sensitive to the evidence being deployed: read the footnotes! 5. Conclusion: Change & Continuity (or, ‘Hammers & Anvils’) a) a society in the making: we can hear the insistent beating of the hammers of change but we hear them only because they ring out against the anvil of continuity b) Contemporaries heard those hammers too: not the just a ‘world WE have lost’, but a world which contemporaries too thought they were in the process of losing References Amussen, Susan. An Ordered Society: Gender and Class in Early Modern England (London, 1988). Braddick, Michael J., & Walter, John. ‘Introduction. Grids of Power: Order, Hierarchy and Subordination in Early Modern Society’, in Michael Braddick and John Walter (eds), Negotiating Power in Early Modern Society: Order, Hierarchy and Subordination in Britain and Ireland (Cambridge, 2001). Clark, Peter & Slack, Paul (eds.) Crisis and Order in English Towns, 1500-1700: Essays in Urban History (London, 1972). Cressy, David. Literacy and the Social Order: Reading and Writing in Tudor and Stuart England (Cambridge, 1980). Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400-1580 (New Haven, 1992). Goody, Jack, & Watt, Ian. 'The Consequences of Literacy' in Jack Goody (ed.), Literacy in Traditional Societies (Cambridge, 1968). Hobsbawm, Eric J. Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Manchester, 1959). Laslett, Peter. The World We Have Lost Further Explored (London, 1965). Macfarlane, Alan (ed.). The Diary of Ralph Josselin, 1616-1683 (London, 1976). Outhwaite, R.B. Inflation in Tudor and Stuart England (London, 1969). Sharpe, J.A. ‘Debate: The History of Violence in England, Some Observations’, Past & Present 108 (August 1985), 206-15 [JSTOR]; cf. Lawrence Stone, ‘Debate: The History of Violence in England, A Rejoinder’, Past & Present 108 (August 1985), 216-24 [JSTOR]. Slack, Paul. Poverty and Policy in Tudor and Stuart England (London, 1988), Thompson, E.P. The Making of the English Working Class (London, 1963). Thompson, E.P. ‘History From Below’, Times Literary Supplement (1966) Trevelyan, G.M. English Social History (London, 1924). Weatherill, Lorna. Consumer Behaviour and Material Culture in Britain, 1660-1760 (London, 1988) Wrightson, Keith. ‘The Family in Early Modern England: Continuity and Change’, in Stephen Taylor, Richard Connors & Clyve Jones (eds), Hanoverian Britain and Empire: Essays in Memory of Philip Lawson (Woodbridge, 1998) Wrigley, E.A., & Schofield, R.S. The Population History of England, 1541-1871: A Reconstruction (Cambridge, 1981). SH: 8.x.2009