Tokugawa shogunate

advertisement

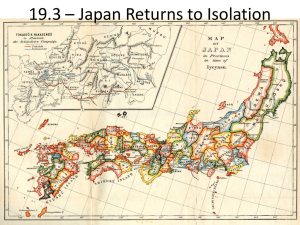

Tokugawa shogunate From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tokugawa_shogunate The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the Tokugawa bakufu (徳川幕府?) and the Edo bakufu (江戸幕府?),[1] was a feudal regime of Japan established by Tokugawa Ieyasu and ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family.[2] This period is known as the Edo period and gets its name from the capital city, Edo, which is now called Tokyo, after the name was changed in 1868. The Tokugawa shogunate ruled from Edo Castle from 1603 until 1868, when it was abolished during the Meiji Restoration. History See also: Late Tokugawa shogunate Following the Sengoku Period of "warring states" (also known as the "Sengoku Jidai" or "Warring States Era"), central government had been largely reestablished by Oda Nobunaga during the Azuchi-Momoyama period. After the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, central authority fell to Tokugawa Ieyasu who completed this process and received the title of shogun in 1603. In order to become shogun, one traditionally was a descendant of the ancient Minamoto clan. Society in the Tokugawa period, unlike the shogunates before it, was supposedly based on the strict class hierarchy originally established by Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The daimyo, or lords, were at the top, followed by the warrior-caste of samurai, with the farmers, artisans, and traders ranking below. In some parts of the country, particularly smaller regions, daimyo and samurai were more or less identical, since daimyo might be trained as samurai, and samurai might act as local lords. Otherwise, the largely inflexible nature of this social stratification system unleashed disruptive forces over time. Taxes on the peasantry were set at fixed amounts which did not account for inflation or other changes in monetary value. As a result, the tax revenues collected by the samurai landowners were worth less and less over time. This often led to numerous confrontations between noble but impoverished samurai and well-to-do peasants, ranging from simple local disturbances to much bigger rebellions. None, however, proved compelling enough to seriously challenge the established order until the arrival of foreign powers. Toward the end of the 19th century, an alliance of several of the more powerful daimyo, along with the titular Emperor, finally succeeded in the overthrow of the shogunate after the Boshin War, culminating in the Meiji Restoration. The Tokugawa Shogunate came to an official end in 1868, with the resignation of the 15th Tokugawa Shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu and the "restoration" (Ōsei fukko) of imperial rule. Government Shogunate and domain Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu The bakuhan taisei (幕藩体制) was the feudal political system in the Edo period of Japan. Baku, or "tent," is an abbreviation of bakufu, meaning "military government" — that is, the shogunate. The han were the domains headed by daimyo. Vassals held inherited lands and provided military service and homage to their lords. The Bakuhan Taisei split feudal power between the shogunate in Edo and provincial domains throughout Japan. Provinces had a degree of sovereignty and were allowed an independent administration of the Han in exchange for loyalty to the Shogun, who was responsible for foreign relations and national security. The shogun and lords were all daimyo: feudal lords with their own bureaucracies, policies, and territories. The Shogun also administered the most powerful han, the hereditary fief of the House of Tokugawa. Each level of government administered its own system of taxation. The Shogun had the military power of Japan and was more powerful than the emperor, who was a religious and political leader. The shogunate had the power to discard, annex and transform domains. The sankin kōtai system of alternative residence required each daimyo would reside in alternate years between the han and attendance in Edo. In their absence from Edo it was also required that they leave family as hostages until their return. The huge expenditure sankin-kotai imposed on each han helped centralize aristocratic alliances and ensured loyalty to the Shogun as each representative doubled as a potential hostage. Tokugawa's descendants further ensured loyalty by maintaining a dogmatic insistence on loyalty to the Shogun. Fudai daimyo were hereditary vassals of Ieyasu, as well as of his descendants. Tozama, or "outsiders", became vassals of Ieyasu after the battle of Sekigahara. Shinpan, or "relatives", were collaterals of Tokugawa Hidetada. Early in the Edo period, the shogunate viewed the tozama as the least likely to be loyal; over time, strategic marriages and the entrenchment of the system made the tozama less likely to rebel. In the end, it was the great tozama of Satsuma, Chōshū and Tosa and to a lesser extent Hizen that brought down the shogunate. These four states are called the Four Western Clans or Satchotohi for short.[3] The number of han (roughly 250) fluctuated throughout the Edo period. They were ranked by size, which was measured as the number of koku that the domain produced each year. One koku was the amount of rice necessary to feed one adult male for one year. The minimum number for a daimyo was ten thousand koku; the largest, apart from the shogun, was a million. Shogun and emperor Despite the establishment of the shogunate, the emperor in Kyoto was still the legitimate ruler of Japan. Regardless of the political title of the emperor, the "shoguns of the Tokugawa family controlled Japan."[4] The administration (体制 taisei?) of Japan was a task given by the Imperial Court in Kyoto to the Tokugawa family, which they returned to the court in the Meiji Restoration. The shogunate appointed a liaison, the Kyoto Shoshidai (Shogun's Representative in Kyoto), to deal with the emperor, court and nobility. Shogun and foreign trade A 1634 Japanese Red seal ship Sakurada Gate at Edo Castle, the center of Tokugawa rule Foreign affairs and trade were monopolized by the shogunate, yielding a huge profit. Foreign trade was also permitted to the Satsuma and the Tsushima domains. The visits of the Nanban ships from Portugal were at first the main vector of trade exchanges, followed by the addition of Dutch, English and sometimes Spanish ships. From 1603 onward, Japan started to participate actively in foreign trade. In 1615, an embassy and trade mission under Hasekura Tsunenaga was sent across the Pacific to Nueva Espana (New Spain) on the Japanese-built galleon San Juan Bautista. Until 1635, the Shogun issued numerous permits for the so-called "red seal ships" destined for the Asian trade. After 1635 and the introduction of Seclusion laws, inbound ships were only allowed from China, Korea, and the Netherlands. Shogun and Christianity Main article: Kirishitan Followers of Christianity first began appearing in Japan during the 16th century. As a symbol of foreign power over Japanese people, it would normally have been swiftly crushed. Oda Nobunaga, however, embraced Christianity and the western technology that was imported with it, such as the musket. He also saw it as a tool he could use to suppress Buddhist forces[5] Though Christianity was allowed to grow until the 1610s, Tokugawa Ieyasu soon began to see it as a growing threat to the stability of the Shogunate. As Ogosho ("Cloistered Shogun"),[6] he influenced the implementing of laws that banned the practice of Christianity. His successors followed suit, compounding upon Ieyasu's laws. The ban of Christianity is often linked with the creation of the Seclusion laws, or Sakoku, in the 1630s.[7] Institutions of the shogunate Rōjū and wakadoshiyori The rōjū (老中) were the senior members of the shogunate. They supervised the ōmetsuke, machibugyō, ongokubugyō and other officials, oversaw relations with the Imperial Court in Kyoto, kuge (members of the nobility), daimyo, Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, and attended to matters like divisions of fiefs. Normally, four or five men held the office, and one was on duty for a month at a time on a rotating basis. They conferred on especially important matters. In the administrative reforms of 1867 (Keiō Reforms), the office was eliminated in favor of a bureaucratic system with ministers for the interior, finance, foreign relations, army, and navy. In principle, the requirements for appointment to the office of rōjū were to be a fudai daimyo and to have a fief assessed at 50 000 koku or more. However, there were exceptions to both criteria. Many appointees came from the offices close to the shogun, such as soba yōnin, Kyoto shoshidai, and Osaka jōdai. Irregularly, the shoguns appointed a rōjū to the position of tairō (great elder). The office was limited to members of the Ii, Sakai, Doi, and Hotta clans, but Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu was given the status of tairō as well. Among the most famous was Ii Naosuke, who was assassinated in 1860 outside the Sakuradamon Gate of Edo Castle (Sakuradamon incident). The wakadoshiyori were next in status below the rōjū. An outgrowth of the early six-man rokuninshū (1633–1649), the office took its name and final form in 1662, but with four members. Their primary responsibility was management of the affairs of the hatamoto and gokenin, the direct vassals of the shogun. Some shoguns appointed a soba yōnin. This person acted as a liaison between the shogun and the rōjū. The soba yōnin increased in importance during the time of the fifth shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, when a wakadoshiyori, Inaba Masayasu, assassinated Hotta Masatoshi, the tairō. Fearing for his personal safety, Tsunayoshi moved the rōjū to a more distant part of the castle. Some of the most famous soba yōnin were Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu and Tanuma Okitsugu. Ōmetsuke and metsuke The ōmetsuke and metsuke were officials who reported to the rōjū and wakadoshiyori. The five ōmetsuke were in charge of monitoring the affairs of the daimyo, kuge and imperial court. They were in charge of discovering any threat of rebellion. Early in the Edo period, daimyo such as Yagyū Munefuyu held the office. Soon, however, it fell to hatamoto with rankings of 5000 koku or more. To give them authority in their dealings with daimyo, they were often ranked at 10 000 koku and given the title of kami (an ancient title, typically signifying the governor of a province) such as Bizen-no-kami. As time progressed, the function of the ōmetsuke evolved into one of passing orders from the shogunate to the daimyo, and of administering to ceremonies within Edo Castle. They also took on additional responsibilities such as supervising religious affairs and controlling firearms. The metsuke, reporting to the wakadoshiyori, oversaw the affairs of the vassals of the shogun. They were the police force for the thousands of hatamoto and gokenin who were concentrated in Edo. Individual han had their own metsuke who similarly policed their samurai. San-bugyō The san-bugyō ("three administrators") were the jisha, kanjō, and machi-bugyō, which oversaw temples and shrines, accounting, and the cities, respectively. The jisha bugyō had the highest status of the three. They oversaw the administration of Buddhist temples (ji) and Shinto shrines (sha), many of which held fiefs. Also, they heard lawsuits from several land holdings outside the eight Kantō provinces. The appointments normally went to daimyo; Ōoka Tadasuke was an exception, though he later became a daimyo. The kanjō bugyō were next in status. The four holders of this office reported to the rōjū. They were responsible for the finances of the shogunate.[8] The machi bugyō were the chief city administrators of Edo and other cities. Their roles included mayor, chief of the police (and, later, also of the fire department), and judge in criminal and civil matters not involving samurai. Two (briefly, three) men, normally hatamoto, held the office, and alternated by month. Three Edo machi bugyō have become famous through jidaigeki (period films): Ōoka Tadasuke and Tōyama Kinshirō as heroes, and Torii Yōzō as a villain. The san-bugyō together sat on a council called the hyōjōsho. In this capacity, they were responsible for administering the tenryō, supervising the gundai, the daikan and the kura bugyō, as well as hearing cases involving samurai. Tenryō, gundai and daikan The shogun directly held lands in various parts of Japan. These were known as bakufu chokkatsuchi; since the Meiji period, the term tenryō has become synonymous.[9] In addition to the territory that Ieyasu held prior to the Battle of Sekigahara, this included lands he gained in that battle and lands gained as a result of the Summer and Winter Sieges of Osaka. By the end of the seventeenth century, the shogun's landholdings had reached four million koku. Such major cities as Nagasaki and Osaka, and mines, including the Sado gold mine, also fell into this category. Rather than appointing a daimyo to head the holdings, the shogunate placed administrators in charge. The titles of these administrators included gundai,[10] daikan,[11] and ongoku bugyō. This last category included the Osaka, Kyoto and Sumpu machibugyō, and the Nagasaki bugyō. The appointees were hatamoto. Gaikoku bugyō The gaikoku bugyō were administrators appointed between 1858 and 1868. They were charged with overseeing trade and diplomatic relations with foreign countries, and were based in the treaty ports of Nagasaki and Kanagawa (Yokohama). Late Tokugawa Shogunate (1853–1867) Main article: Late Tokugawa shogunate Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the last Shogun, in French military uniform, c.1867 The Late Tokugawa Shogunate (Japanese: 幕末 Bakumatsu) was the period between 1853 and 1867, during which Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy called sakoku and modernized from a feudal shogunate to the Meiji government. It is at the end of the Edo period and preceded the Meiji era. The major ideological and political factions during this period were divided into the pro-imperialist Ishin Shishi (nationalist patriots) and the shogunate forces, including the elite shinsengumi (newly selected corps) swordsmen. Although these two groups were the most visible powers, many other factions attempted to use the chaos of the Bakumatsu era to seize personal power.[12] Furthermore there were two other main driving forces for dissent; first, growing resentment of tozama daimyo (or outside lords), and second, growing anti-Western sentiment following the arrival of Perry. The first related to those lords who had fought against Tokugawa forces at Sekigahara (in 1600 AD) and had from that point on been exiled permanently from all powerful positions within the shogunate. The second was to be expressed in the phrase sonnō jōi, or "revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians". The turning points of the Bakumatsu were the Boshin War and the Battle of Toba-Fushimi, when pro-shogunate forces were defeated.[13]