Clostridium difficile

advertisement

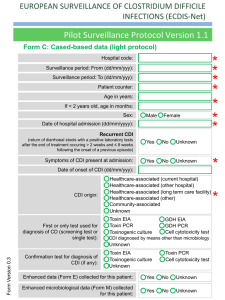

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) Introduction Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is a commonly encountered problem among patients treated with antibiotics. The clinical spectrum can range from mild diarrhea with unformed stools to severe colitis, systemic inflammatory response physiology, and acute abdomen. Recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of CDI have resulted in varying recommendations about diagnostic testing and treatment. This guideline is intended to provide a template for a standardized approach to the management of CDI by the Infectious Disease consult service at Harborview Medical Center. Diagnosis of CDI Until recently, the diagnosis of CDI required a stepwise testing algorithm that included enzyme immunoassays for C. difficile antigen, toxin A, and toxin B, and an in-house PCR assay for toxin B. The HMC microbiology laboratory recently switched to a FDA approved polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (Cepheid, Xpert C. difficile) for diagnosis of CDI. This rapid assay uses real-time PCR directed to conserved nucleic acid target sequences from toxigenic strains of C. difficile. Detection of Toxin B provides ~95% sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of CDI [1, 2]. The presence or absence of Toxin B is reported by the laboratory. The assay also detects the presence of Binary Toxin and the tcdC deletion, mutations that have been detected in epidemic strains of C. difficile [3]. When present, the presence of this mutation is also reported by the laboratory. Use of the new assay has greatly simplified the diagnostic algorithm, as detailed here: 1. Diagnostic testing is appropriate in patients with a combination of antibiotic exposure and unformed stools (which are not always watery) [4]. Patients can be asymptomatically colonized with toxigenic strains of C. difficile [5], so it is important that testing only be performed in appropriate clinical settings. a. There are situations in which CDI can occur without diarrhea, including ileus, toxic megacolon, use of opiates or other antiperistaltic drugs, Hirschprung’s disease, and cystic fibrosis [6-11]. 2. In general, the microbiology laboratory will not perform testing for C. difficile on formed stool; a specimen must take the form of the collection container to be considered liquid. If testing is required because of a clinical scenario in which CDI is being considered despite the absence of diarrhea, the laboratory should be notified. 3. Results of the C. difficile toxin assay should be available the same day. 4. In patients with a high clinical suspicion for CDI and those with severe disease, initiate enteric pathogen precautions and empiric therapy while awaiting test results. 5. If test is positive, treat for CDI (see below). 6. In patients with a negative Xpert C. difficile real-time PCR assay, an alternate diagnosis should be sought. a. Although this assay is much more sensitive than EIA or tissue culture assays, no test is 100% sensitive. Therefore, if clinicians strongly suspect the diagnosis despite a negative test, they may choose to treat as if the patient has CDI. Repeat testing is not encouraged, as this is very low yield [12, 13]. Treatment of first episodes of CDI Treatment includes a combination of antibiotic therapy directed at C. difficile and, where possible, discontinuation of the antibiotic(s) that precipitated CDI [14]. Anti-motility agents should be avoided, as they may increase the risk of severe CDI and toxic megacolon. Until recently, all first episodes of CDI were always treated with oral metronidazole. In the past few years, a number of studies have suggested that in patients with more severe disease, oral vancomycin may be superior. However, the definition for “severe” episodes of CDI remains an area of debate. At present, data support the following strategy for management of first episodes of CDI: 1. Assess disease severity; patients with one or more of the following should be considered for first-line oral vancomycin therapy. Criteria have varied in different studies [15, 16], and remain an area of debate. Clinical judgment remains important in interpreting these criteria. a. WBC >15,000-20,000 cells/μL b. Age >60 years c. Temperature >38.3°C d. Hypotension/shock e. Serum albumin <2.5 mg/dL f. Endoscopic evidence of pseudomembranous colitis g. Treatment in the intensive care unit 2. For non-severe first episodes of CDI, the treatment of choice remains oral metronidazole 500mg po q8h for 14 days. 3. If patients with non-severe CDI fail to respond clinically within 3-5 days, switch to oral vancomycin 125mg po q6h to for the remainder of 14 day course. 4. For severe CDI, first-line treatment should be with vancomycin 125mg po q6h for 14 days [15]. a. In patients who cannot use the enteral route for delivery (e.g. with ileus or obstruction), initiate metronidazole 500 mg IV q8h. b. In patients who cannot tolerate oral or VT vancomycin from above, retention enemas may be considered based on favorable data from a small number of case reports and case series [17-19]. Vancomycin 0.5-1 gram in 1-2 liters of normal saline is instilled as a ~60 minute retention enema q4-12 hours or at the time of decompressive colonoscopy. c. Tigecycline may be a therapeutic option for severe CDI, used either as an alternative or an adjunct to vancomycin enemas and IV metronidazole [20]. 5. General surgery and Gastroenterology should be consulted in severe cases, as procedures including decompressive colonoscopy and colectomy may be required for complications including toxic megacolon, perforated viscus, or necrotizing colitis. 6. If it is not possible to discontinue the inciting antibiotics, consider continuing low-dose metronidazole or vancomycin until other broad-spectrum antibiotics have been discontinued for 7 days. Treatment for Second Episode of CDI Regardless of the initial antibiotic regimen, relapse of CDI occurs in >10% of cases [21]. Management of initial relapse of CDI includes the following: 1. The diagnosis of relapses of CDI is clinical, based on initial resolution and then subsequent return of symptoms. Repeat testing is not helpful, as the assay may remain positive for months after the first episode. 2. If a patient with prior CDI has recurrent diarrhea and the clinician does not suspect CDI as the cause of the recurrence, the laboratory is willing to perform a PCR on a repeat stool specimen. 3. Antibiotic selection for first relapse of CDI should follow the same guideline as for the initial episode. Specifically, antibiotic treatment should be stratified with metronidazole for non-severe cases and vancomycin for severe illness. Treatment for Additional Episodes of CDI Unfortunately, patients with an initial relapse of CDI are at substantial risk for additional episodes. Strategies using prolonged treatment with vancomycin have been evaluated in a relatively large non-randomized study [22]. The role of probiotics and fecal biotherapy remains controversial (Kelly UTD). A small case series has suggested that the addition of rifaximin following treatment with vancomycin may be associated with a favorable cure rate [23]. Management of additional relapses of CDI should include: 1. Vancomycin treatment followed by a three week vancomycin taper. The recommended regimen includes: a. Vancomycin 125mg po q6h for 14 days, then b. Vancomycin 125mg po q8h for 7 days, then c. Vancomycin 125mg po q12h for 7 days, then d. Vancomycin 125 mg po ad for 7 days 2. Most patients with a third episode of CDI should receive the vancomycin regimen above without additional medications or probiotics. For patients with 4 or more episodes, consideration may be given to adjunctive measures, although data are limited: a. A small case series has demonstrated cure in 7 of 8 women with recurrent CDI following sequential treatment with vancomycin then rifaximin. The most commonly used rifaximin regimen in this study was 400mg po bid for 14 days after the vancomycin taper [23]. b. Probiotic therapy may be considered on a case-by-case basis. The potential benefits should be weighed against the potential risk of bacteremia or fungemia with the probiotic agents [24]. c. Fecal bacteriotherapy (the transplantation of stool from another individual, typically a family member, to the patient) appears effective in some published case series, and may also be considered on a case-by-case basis for patients with multiple recurrences [25]. Additional References of Interest Cohen SH, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010 May;31(5):431-55. Larson AM, Fung AM, Fang FC. Evaluation of tcdB real-time PCR in a three-step diagnostic algorithm for detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 2010 Jan;48(1):124-30. Novak-Weekley SM, Marlowe EM, Miller JM, Cumpio J, Nomura JH, Vance PH, Weissfeld A. Clostridium difficile testing in the clinical laboratory by use of multiple testing algorithms. J Clin Microbiol. 2010 Mar;48(3):889-93. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Huang H, Weintraub A, Fang H, Nord CE. Comparison of a commercial multiplex real-time PCR to the cell cytotoxicity neutralization assay for diagnosis of clostridium difficile infections. J Clin Microbiol 2009,47:3729-3731. Peterson LR, Manson RU, Paule SM, Hacek DM, Robicsek A, Thomson RB, Jr., Kaul KL. Detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile in stool samples by real-time polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of C. difficile-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 2007,45:1152-1160. McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A, Owens RC, Jr., Kazakova SV, Sambol SP, et al. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med 2005,353:2433-2441. O'Connor D, Hynes P, Cormican M, Collins E, Corbett-Feeney G, Cassidy M. Evaluation of methods for detection of toxins in specimens of feces submitted for diagnosis of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol 2001,39:2846-2849. McFarland LV, Elmer GW, Stamm WE, Mulligan ME. Correlation of immunoblot type, enterotoxin production, and cytotoxin production with clinical manifestations of Clostridium difficile infection in a cohort of hospitalized patients. Infect Immun 1991,59:2456-2462. Burke GW, Wilson ME, Mehrez IO. Absence of diarrhea in toxic megacolon complicating Clostridium difficile pseudomembranous colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1988,83:304-307. Sheikh RA, Yasmeen S, Pauly MP, Trudeau WL. Pseudomembranous colitis without diarrhea presenting clinically as acute intestinal pseudo-obstruction. J Gastroenterol 2001,36:629-632. Zahariadis G, Connon JJ, Fong IW. Fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis without diarrhea: lack of emphasis in diagnostic guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol 2002,97:2929-2930. Bahadursingh AN, Vagefi PA, Longo WE. Fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis in a patient with spinal cord injury: case report. J Spinal Cord Med 2004,27:266-268. Razzaq R, Sukumar SA. Ultrasound diagnosis of clinically undetected Clostridium difficile toxin colitis. Clin Radiol 2006,61:446-452. Ghai S, Ghai V, Sunderji S. Fulminant postcesarean Clostridium difficile pseudomembranous colitis. Obstet Gynecol 2007,109:541-543. Aichinger E, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Nyre LM, Patel R. Nonutility of repeat laboratory testing for detection of Clostridium difficile by use of PCR or enzyme immunoassay. J Clin Microbiol 2008,46:3795-3797. Peterson LR, Robicsek A. Does my patient have Clostridium difficile infection? Ann Intern Med 2009,151:176-179. Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea caused by Clostridium difficile. In. Edited by Calderwood SB, Baron EL. April 12, 2010 ed. ed: UpToDate Online; 2010. Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis 2007,45:302-307. Pepin J, Valiquette L, Alary ME, Villemure P, Pelletier A, Forget K, et al. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1991 to 2003: a changing pattern of disease severity. CMAJ 2004,171:466-472. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. Apisarnthanarak A, Razavi B, Mundy LM. Adjunctive intracolonic vancomycin for severe Clostridium difficile colitis: case series and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2002,35:690-696. Shetler K, Nieuwenhuis R, Wren SM, Triadafilopoulos G. Decompressive colonoscopy with intracolonic vancomycin administration for the treatment of severe pseudomembranous colitis. Surg Endosc 2001,15:653-659. Nathanson DR, Sheahan M, Chao L, Wallack MK. Intracolonic use of vancomycin for treatment of clostridium difficile colitis in a patient with a diverted colon: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 2001,44:1871-1872. Herpers BL, Vlaminckx B, Burkhardt O, Blom H, Biemond-Moeniralam HS, Hornef M, et al. Intravenous tigecycline as adjunctive or alternative therapy for severe refractory Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 2009,48:1732-1735. Kelly CP, Pothoulakis C, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile colitis. N Engl J Med 1994,330:257-262. McFarland LV, Elmer GW, Surawicz CM. Breaking the cycle: treatment strategies for 163 cases of recurrent Clostridium difficile disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2002,97:1769-1775. Johnson S, Schriever C, Galang M, Kelly CP, Gerding DN. Interruption of recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea episodes by serial therapy with vancomycin and rifaximin. Clin Infect Dis 2007,44:846-848. Davidson LE, Hibberd PL. Clostridium difficile and probiotics. In. Edited by Calderwood SB, Baron EL. UpToDate Online version 18.1 ed: UpToDate Online; 2010. Borody TJ, Leis S, Pang G, Wettstein AR. Fecal bacteriotherapy in the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. In. Edited by Rugtgeerts P, Ginsburg CH. UpToDate Online volume 18.1 ed: UpToDate Online; 2010. Acknowledgement My sincere thanks to Ferric Fang, Paul Pottinger, and Bob Harrington for their questions, comments, and suggestions on this guideline.